Podcast: Download (Duration: 1:03:00 — 51.2MB)

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

I've been writing in journals since I was 15. They have been my escape and my therapy, my creative expression and a record of my lowest times and my highest achievements. Journals are more than blank paper. They represent possibility. In today's show, I talk to Joel Friedlander about his new premium journal.

In the intro, I talk about the implications of Netflix's global shift and what we can learn from their continued expansion. [ Guardian / Digital Trends / The New Publishing Standard]

In the intro, I talk about the implications of Netflix's global shift and what we can learn from their continued expansion. [ Guardian / Digital Trends / The New Publishing Standard]

The edits are done for How to Write Non-Fiction. Onto formatting for print and re-jigging for audio to make it an easy read. Pre-order available now.

I also mention BookBlock.com for anyone who might want to make their own journal.

Joel Friedlander is an author, book designer, professional speaker, and blogger. He runs TheBookDesigner.com, regularly rated in the top sites for writers, and has courses, templates, and many resources for authors. His most recent project is the WriteWell Writer's Journal.

You can listen above or on iTunes or Stitcher or watch the video here, read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and full transcript below.

Show Notes

- The features that were important to have in the journal

- Hurdles that had to be cleared, including getting the binding right

- On the practicalities of printing, shipping and distribution. [You can also check out the interview with John Lee Dumas on his Mastery Journal which was printed and sold in a different way.]

- The unique story and writing exercise included with each journal

- Changes in the print and digital book space in the last 10 years

You can find Joel Friedlander at TheBookDesigner.com and on Twitter @jf_bookman. Find the journals at WriteWellJournals.com

Transcript of Interview with Joel Friedlander

Joanna: Hi, everyone. I'm Joanna Penn from TheCreativePenn.com, and today I'm back with Joel Friedlander. Hi, Joel.

Joel: Hi, Joanna.

Joanna: Great to have you back on the show. I think it's number four or maybe five on the show over the last nine years.

Joel: Some things it's good to lose track of, I guess. But I'm really happy, and thanks for having me back.

Joanna: It's great to have you on the show. Let's do a little introduction for those people who might not know you.

Joel Friedlander is an author, book designer, professional speaker, and blogger. He runs TheBookDesigner.com, regularly rated in the top sites for writers, and has courses, templates, and many resources for authors. His most recent project, and what we're talking about today, is the WriteWell Writer's Journal, which I have a red copy of here.

Joanna: I'm very excited about this. Those regular listeners will know that about a year ago I flirted with and even met people about doing a journal. You have done a journal, so I'm excited.

You've done so many books over the years. Why a journal, and why now?

Joel: One thing about those books, they all have words in them. And if you think about it, this is a book with no words yet. The words are latent, you might say.

I use journals and notebooks. I've used them for many years. I'm not a journal-er, in that I don't sit and record scenes or what I did that day, but I still use them for notes, for talking with clients, for developing ideas, drawing mind maps, whatever, recording conversations I'm having. Because I realized a long time ago if I write it on a three by five card I'm going to lose them.

And if it is in a journal, you're not going to lose it. So, I love journals, I've been using them for many years. I have stacks, my wife has even bigger stacks.

The problem is, Joanna, I'm a professional book constructor in a sense. And many of these journals, some of them are lovely, and many of them are very irritating. Which is a problem when you have a little perfectionist streak. I've thought for a long time I could do that better because I know how to put books together.

This year I've really been more interested in doing more personal projects, because I've been doing other people's projects for so long. I'm really interested in working on my own projects, and this is a project I knew that would bring me a lot of joy as well as help other people.

Does it get any better than that?

Joanna: I love it.

Joel: I understand why you went into and then out of this project because it's actually quite daunting. And even though I've been in hundreds of books over the years, and I know all about bookbinding and papers and adhesives and all that stuff, this project stumped me.

I thought it was going to take about six weeks, and it took over a year to put together the materials, the way of manufacturing, the right vendor, and it was very, very challenging, but I'm very pleased with the outcome.

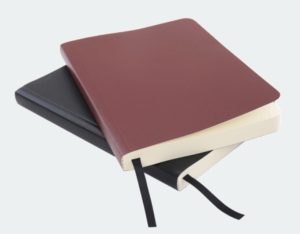

Joanna: We're gonna get into the challenges because I definitely think they're underestimated. But let's first talk about the features that were important to you when you went into this. And like you said, “I can do it better.” So, what are the features? For example, are you, having been down this path, it's interesting. The cover you sent me, this I would say oxblood, is it an oxblood?

Joel: Cranberry, we call it.

Joanna: I'm a thriller writer. I prefer oxblood. But it's like a dark red, to those who are not watching the video. So if you're on audio only, I've got the kind of cranberry. And it's got these rounded corners, which I know are impressive. What were some of the other things? It's got a ribbon, I've got the little ribbon here.

What are the other features that were important to you and that impacted the design process the most? And what are things that people take for granted that are really hard?

Joel: There are a lot of elements that come into creating physical products, and we're going to talk a little bit about that. And books are no different.

A book is a physical product, and a journal is even more so because this isn't restricted to bookstores particularly. You can sell them anywhere. But there are a lot of manufacturing demands and financial demands to doing it.

What I was looking to do was to correct some of the errors or irritations that I had using other journals.

For instance, the journal that won't lay flat. That was my number one goal. And you could see it from this journal here, for those who are watching this, that these journals will open flat anywhere you open it in the book.

If you have one that's like a hardcover journal, you may have experienced leaning your elbow on one side, so you could write on the other side. Well, I just felt that is wrong. Journals should be a pleasure to use, and it should lay flat so you can write in it easily.

The rounded corners were really important to me because these are very mobile. People carry their journals with them, they stick them in their purse or their briefcase, or even in their pocket, or their backpack.

Square corners tend to get banged very easily, and they get dog-eared, and they fold over. I don't like that. So the solution to that is the round corner, and that does take special finishing at the printer.

The paper, obviously, was super important that it be able to absorb all kinds of writing instruments well. The way the interior was laid out, and mine, you can tell that I'm a minimalist because I created this journal specifically for writers, not for sketch artists, or bullet journal planners, or productivity people.

This is just a canvas for writers to write, and it was optimized for that. So, there's no interruptions, it's just lines on the page.

Now, Joanna, I know you like the blank page, but…and my first go around, I thought lines, or rules as we call it in printing, would be important, so that the lay-flat binding, the round corners, the good paper, the minimalist interior, the ribbon you have to have.

If you don't have a ribbon, it's really hard to sell it as a journal. You use the place marker or not, because a lot of people just stick pieces of paper, business cards, whatever in there, but if it doesn't look like a journal without the ribbon…

Joanna: That's interesting.

Joel: That's a critical visual cue.

Joanna: And hasn't it got more pages in?

Joel: Most of the journals sold in the U.S. run between 160 and 192 pages, and one of my problems with that is you have to keep replacing them.

These journals, WriteWell journals, have 240 pages, substantially larger, and they won't need to be replaced as often.

I also was very irritated over the years by trying to find things in my journal. Maybe I wrote down an idea for, and this is actually true, an idea for a bean dip recipe. And one day I went to try and find it, and I must have spent 15 minutes just leafing, leafing, leafing, leafing, leafing. It's so irritating.

So these journals actually have page numbers of pages. And then at the end, there's an index page where you can actually create a little index to what you've written, and you can find it right away. I thought that was a pretty good innovation.

And lastly, I would say many of the journals I've bought tend to be kind of narrow, and I don't know if manufacturers make them that way so they're easier to fit in your purse or pocket. But I find them a bit claustrophobic because I just get to the end of the line too soon.

So I intentionally made these journals wider than the normal ones. And I'm very, very happy with the results.

Those are some of the product innovations that I put into WriteWell journals, and I believe they're unique. I don't know of another journal on the market that has these kind of qualities. And then also, Joanna, all the feedback I'm getting is extremely positive.

Joanna: We should say, again, if people aren't on the video that it's about A5. Is it A5 size? Because we haven't really said what size it is.

Joel: Exactly.

Joanna: Yeah, so it's A5. I like the A5.

Joel: We don't use A5 in the U.S., so it's an inch measurement. But, yes, it's basically exactly A5.

Joanna: I like that size, too, because I don't want an A4 journal, that feels like school. I have some of those tiny journals, I've got some on my desk here. But they're too small and like you say, you can't get many words on the page. I think this is the most similar to a Leuchtturm.

Have you seen a Leuchtturm?

Joel: Yes, I have. They came out in the U.S. when I was about three-quarters of the way through my product development, and the Leuchtturm is the closest I've seen to what I put together. It was actually kinda freaky because they're doing the things that I'm doing, and they're very nice journals, Leuchtturm.

Joanna: They are, yes. Let's just go into it a bit more.

They lie flat, because when I had this conversation with the publisher that I went in to see, and the first thing I said was, “It has to lie flat.” And they just looked at me like, “Oh, my goodness, what are you talking about?”

Can you explain a bit more about the types of binding, and why this is such a big deal? And how you got over that with the binding that you use?

Joel: You also had asked me earlier about cost factors of producing these. And by far, on this journal, the binding is the biggest cost factor. To get that real lay-flat binding.

There are many ways to bind books, and part of the reason it took me so long to develop this, I'd never actually done a book with a flexible cover. Because I really love that flexible feeling. It just feels luscious to me, and rich, and I just really like it.

When I first started talking about this, I was talking to Robin Cutler you may know who's the manager of IngramSpark. And she said, “Oh, that's great, Joel. Do them at IngramSpark and I'll help you out.”

I said, “Geez, Robin, I would love to do that, but I can't.” You can't POD these books, because print-on-demand books use what's called a perfect binding where all ends of the pages are glued to the cover. They're chopped off and then glued to the cover.

You'll notice on the print-on-demand books, the spine is kinda tight. So, they won't open fully and they won't lay flat. And if you try to do that, you're going to break the spine, and you do stand the risk at that point of pages starting to fall out.

That's not a good solution. So, this binding is called a “soft side case binding,” and the cover material is actually glued to a piece of paper that runs throughout the whole back spine of the book, and that's what the book block is glued to.

And in this case, the pages are all sewn into the binding, so they can never come out. You would have to, like, physically tear the book apart to make them come out.

If you open it fully, you'll see little threads, the marks of little threads in the book. So, it's done on a case binding machine, which is what's used for doing hardcover books. But instead of a bordered case that's hard, this uses this custom material I had made, another cost factor, because I couldn't find the exact thing I wanted, so I had to have it custom done.

With this kind of green, and the soft finish, and the flexibility, so the binding on these journals is really, really good. And like I say, you can fold them all different kinds of ways and they're never going to come apart.

But doing that is a lot more expensive than perfect binding, which is a totally automated process where they chop the books, they glue things on, they bring a knife down and trim them, that's it, you're finished. That can be done very inexpensively.

But if you want a true lay-flat binding, it does cost money. And that's one of the reasons why the journals have the retail price they do here in the U.S., which they retail for $22.

Joanna: I think that's really interesting. Generally, I buy Leuchtturms or Moleskines. I think they retail here in the U.K. for around £12, £15, which would be similar price to a $22. And a lot of people say, “Oh, that's so expensive,” but it's not.

I think what you're saying is so interesting because I have, behind me I've got shelves and shelves of journals as well. The journal is emotional. It's an emotional product.

Of course, we all love books. In print, an e-book, an audio, whatever. But it's a taking approach. Reading a book is a taking approach, and the product, you take from the product.

But the journal, you emotionally are involved with it, and what you write in it becomes part of your life, it's so important. I love the fact that you've got a custom material because it does feel really nice. It's hard to describe.

How would you describe it? Because it's not leather.

Joel: It's got a grain to it.

Joanna: Yes, it's got a grain, but it's not plastic-y. That's important, it's not plastic-y.

Joel: It's kind of a loose grain.

This is something you find out that's actually kinda cool when you start talking to manufacturers, material suppliers. You don't usually have to settle for just what they have. You can actually create something that doesn't exist.

And so by combining the kind of grain, the weight of the cover, the color, and the actual finish on it, this very soft finish that's not high gloss, and it's not dead matte, it's kinda somewhere in between, you can create something unique.

The word I use for this experience is it's intimate. People are very intimate with their journals because you're writing sometimes stuff that nobody else will ever see. A lot of people use journals.

I'm in Northern California. It's the human potential movement headquarters here. People at workshops, meditations, and retreats. And they're doing psychological processing by writing stuff. It's very sensitive material.

That sense of intimacy and personal connection you have with the object that you're expressing yourself in, I think, is really crucial to what I was trying to achieve with this journal.

Joanna: Let's talk about the money in a couple of ways. First of all, when I went down this process, the actual reason I stopped is because in the U.K., blank journals, and I like blank journals, are taxed as stationery rather than books. And in Britain, we have VAT, a sales tax on stationery, that we don't have on print books.

And there's a certain percentage of text that you have to have, to have something classified as a book so that the sales tax is different. I would have had to go through all these different hoops to do stationery.

What was that like in the U.S.? Did it became a different product, that you're now a stationer?

Joel: No, it's actually totally different. It's a non-issue in the United States. And part of the reason for that is because sales taxes are all locally administered.

In other words, we have no national sales tax in the U.S. Some states have a sales tax. Some counties have a sales tax, which is added to the state's sales tax.

Some places like where I'm sitting also have a city sales tax, so we have a City of San Rafael, County of Marin, State of California, add them all up. When you go into a shop down the street here, you're going to pay about seven and a half percent sales tax, but you're gonna pay that on anything.

Hot tubs, cars, journals. There's no discrimination about the kind of product you're buying, there's a flat tax on anything you buy at retail. And the retailer has to collect the tax, and then report it and pay it to the appropriate government.

It's much simpler. There's no discrimination between different types of products at this level.

Joanna: It doesn't make any difference. And it's interesting because, of course, and again, most authors who are listening don't have to worry about sales tax because usually we use Amazon KDP, Kobo, Apple. They deal with that and we just get the money later.

But what we're talking about here is not using print on demand.

Tell us how did you do this practically with a print run, how were you selling them, and then how will you continue to sell them in terms of distribution?

Joel: That's all really interesting. But I would like to point out one thing, Joanna, and that is that the vast majority of print books sold in the United States, and I'd reckon it's probably the same in the U.K., are offset printed books.

The vast, vast, vast, vast, vast majority of printed books, even though in the indie publishing community, a print book is almost defined as a POD product.

I remember when Guy Kawasaki came out with his book, “APE: Author, Publisher, Entrepreneur.” You remember that a few years ago? He didn't have anything in there about books printed offset. And I actually complained to him about that.

I said, “Guy, you're putting this book out here, but you're ignoring most of the book's printing.” And the fact is that, many self-publishers don't know this, but there's a long tradition, very active tradition of self-publishers publishing print books through offset printing, distribution, and actually getting to that whole system.

Basically, you have to contract with a manufacturer, and part of my challenge with the journals was finding a manufacturer who could do what it was I was trying to do.

I spoke to at least three dozen printers, I would say, over the course of time. Rather frustrating because some of them would say they could do it, but then they couldn't, so you have to vet your supplier. You do have to have capital because you have to pay everything upfront.

In print on demand, we don't pay anything, basically. Over at Ingram you might have to pay to upload your files, but when they print the books, they don't come and ask you for the money. They deduct the money from the cost that the buyer is paying.

So, yes, the book printers will not ship your books without having a complete payment for the entire print run in their hands before they kick those books off the shipping dock. They won't start your project without having, like, a third to a half of the anticipated expense.

But I do print books for clients all the time, and so this is not really that esoteric. Obviously, my journal is an unusual product.

But as far as having a print book, your print runs are gonna start at about 500 copies. Because under that it doesn't really make financial sense, you're going to be paying too high a cost.

My guideline for authors, usually, is that I say to them, “If you can tell me for sure that you can sell, like, 500 books over the next 6 months, I'm going to tell you, ‘Go get them printed' because they're going to cost you half as much as what the print on demand vendor is charging you.”

Now, print on demand is very convenient, but once you understand how this whole print, distribute, retail system works, then it's not really that hard to get into it. Now, for my purposes, my journal ended up creeping up in cost as the production went along.

I started off with a really great estimate. Man, I was excited that, “Whoa, I'm going to make money on this project.” Actually the cost kept creeping up.

So, I got to the point where they're profitable, and I'm not complaining about the profit, but if you wanna distribute the books, in other words, if I want to have a lot of retailers selling them, then I have to have a pretty low unit cost compared to my retail price.

And the reason for that is that everybody in the distribution chain has to make a profit, so they add something to your cost.

Let's say I have a book that sell for $10 retail, my distributor may only pay me $3 for that book. That's a 70% discount. Three fifty maybe, a 65% discount. So, from that $3.50 on my $10 book, I have to pay for the manufacturing of the books, the shipping of the books, and hopefully to have any profit left over.

This is the subject of many consultations I have with people, figuring out this whole matrix between the kind of book you're producing and your marketing. Because the marketing is what should influence that production, not the author's idea of what wonderful thing I wanna create. I don't know if I answered your question, Joanna.

Joanna: You have this great blog post about the impossible book project, and that related to this sort of thing. It's like, “Oh, I want gold leaf, and embossing, and stamping, and my thing on the back, and a hardcover.”

All of those things add cost in the same way that adding the rounded corners adds a surprising cost, right? So all of these decisions make a difference.

The question was how are you selling them? Is it all preorders for the print run, or are you going to have them shipped to Amazon and do Amazon retail?

Joel: I am not selling on Amazon right now, and I am not retailing at the moment. I'm doing all direct selling, and that's because developing the journal was expensive.

I put in a year of work and I've got stacks and stacks of samples here, and journals, and prototypes. And at the cost that I'm paying now for the journals, I decided to start off this whole enterprise by direct selling.

You asked me at the beginning, “Why did I do this,” you know. But I looked at my website and my email list, and I said, “Wait a second, I have tens of thousands of writers.”

I knew that eight years ago, but for some reason the light bulb went off, and I thought, “Whoa, this is a perfect something I'd love to do, and then I know my readers would love to buy because who doesn't want a really nice writer's journal if you're a writer?”

I did do a presale, and I did it explicitly to raise the money to pay the second half of the printer's invoice because that makes sense. I'm doing this to put these into the hands of writers. So, if I can offer you a discount on a presale, we did fairly well.

We sold several hundred journals on the presale, collected all the money I needed to pay that second invoice from the printer, it all worked out great.

Now, I'm only doing direct sales. But this is just a beginning of this product line. The whole idea going into it wasn't just to create a journal, but it was to take these innovations.

For instance, the next set I'm working on have many of this same innovations, but they'll be less expensive, and because they'll have paperback covers.

Now, I would like to talk about the covers just for a second. This is the kind of thing you can do when you control the whole production process.

It used to be in the old days when all books were offset printed that we frequently did split runs. So a split run would be we would print let's say 2,000 books, the interior, the book block. And then we would bind up 1,500 as paperbacks, and then bind up the other 500 as hardcovers.

Because that really is not very expensive to do, surprisingly, if you compare it to the price you can demand for a hardcover book. Just like $10 higher than a paperback book, yeah. But the cost factor is only by an extra dollar or two, so it really is very cost effective.

So I took the same approach. I said, “Well, I could do a journal.” And when I talked to the people supplying the cover material, I said, “You know, what's the minimum quantity to produce this custom material?”

And when they told me, I realized I could do the same thing on these journals. And that's why I ended up with two colors because I thought, “Well, I'll sell more if I can give people a choice, right?” Some people like black, some people don't.

We did a split run. We printed 1,000 journals, and then we split them between the cranberry covers, or oxblood for you thriller people, and black covers. And that gave me, in essence, two products for the price of one.

I'm going to do the same thing on the paperbacks because we're going to do three or four different designs. But all the interiors will be printed at once, and then they'll just be bound up into different covers. So, in effect, I'll do one print run, but I'll have four different products.

Joanna: It's so interesting because this is such a different world to the kind of print on demand model that most people listening will be using. And although the downside is, yes, you have to pay upfront and do all these design work, what you're now doing is not just stopping.

Basically, the one I have here is more of a prototype in a way that you're going to be doing a lot more products. But that's really interesting to me. Also, you say a paperback cover.

This is called a soft cover? Because it's not hardback.

Joel: No, no, no. It's not hard, but what I'm talking about is that paperback book has paper that's been printed, right? All your books on your shelf are paperbacks. They have printed paper covers that are wrapped on the interior.

In this case, I'm using this special material, the binding. But I could have also just taken paper just like your covers, and printed them, and wrapped them in that, and had everything else the same. It's less expensive because this cover material is a premium-priced product.

Joanna: I wanted to ask you about the little insert that comes with it, which is the WriteWell story, and it's how to free write. It's got information on what the book is like, for people on the video.

And then it's an A4 that's folded, and it's got a little letter from you including your signature. It's very personal, and it talks about free writing, but it also tells you about the product. Now, you're a marketing genius, so…well, you're very good at marketing.

Joel: I took that idea straight from Moleskine.

Joanna: But you made it very personal.

Joel: And then I created my own version. What I found interesting, Joanna, was I was looking at the packaging on Moleskine. They come shrink-wrapped, which is good, and a product like this should be shrink-wrapped because the customer wants to buy it and cut that open.

It's really important, and you know it's pristine. And it's also good because even if you don't open those for a year, when you undo the shrink wrap, they're gonna be like they just came from the printer.

Really important, if you're doing print books, I recommend shrink wrapping them in bundles which is less expensive. And it's just to maintain the integrity of the book.

Here's what's interesting. I was looking at the Moleskines and they have the wrap on the book, and then it's shrink wrapped, and then it tells you what kind of Moleskine, and you flip it over and they tell you the size.

And then the only thing that it says on there, it says, “Inside, the Moleskine story.” I found that very interesting from a marketing point of view.

Was somebody clambering for the Moleskines story? Was that a big demand? That's the only pull they had. But Joanna, we talked about this before, the power of story itself is incredible, and it's stories that really sell things.

If you get hooked into the story, and that's why I wanted to tell a little bit the story of creating the journals and how the features that we were talking about solve problems.

That's actually a little mini-course on freewriting. It's from a book I'll be publishing later this year, in fact. All of the free writing I've done has been done in journals like this, so it's a close personal connection for me and I thought that would really come through.

I added my signature, I used it in many of my emails, and I really wanted to make it a personal communication between me and whoever is buying that journal. They would see what I had done and why I did it that way.

They're also gonna get a little mini-course in there because that little mini-course really works, by the way. It's good content.

Joanna: It is good content. It reminded me that the reason I started writing in Moleskines back when I was, like, 15, was because of Bruce Chatwin who wrote “In Patagonia” and “Songlines.” He was a travel writer. He tragically died back in the '80s.

The fact that he used Moleskines made me want to use Moleskines, and it connected an empty journal with a writer. I really appreciate this. I think this is genius.

Tell people what is free writing so they know what that is. I have talked about it before, but just explain it?

Joel: Free writing is a great practice. When you free write, you have a prompt and you have a timer. And the instruction is when the timer goes up, you start writing to the prompt. A very simple prompt might be something like “I remember.” It's one of my favorites.

You're dedicated to writing as fast as you possibly can for the assigned period of time. It could be 1 minute, 10 minutes, whatever, it doesn't matter.

The idea is to never take your pen off the page. You can't stop, you can't try to find the right word. What you're attempting to do is to write faster than you can ideate your thought, your ideas. It's a brilliant practice for writers, and I still use free writing sometimes just as a warm-up.

The other day I had some writing to do, and I decided to do a little free writing warm up, and I did an alphabetical free write. This is without a prompt. Just write down all the letters in the alphabet, and then you start free writing, and each word has to start with the next letter of the alphabet.

Now, what this does is it completely defeats your logical mind. It defeats the grammar you have embedded in your language brain, and it allows other things to come out. And, you know, my free writing teacher, Susan Murray, used to always say to us, “No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader.”

I find that to be very true. It's just astonishing the kind of things that you can come in contact with from within yourself in a free writing session because you get very surprised.

Joanna: I agree. I definitely think it's great. I just thought it was fantastic that you had it with the journal. It's almost a bit about you, but a bit about how you could use the journal. So that's fantastic.

We've given lots of tips, but if people are intending to do this kind of special print project, like you mentioned doing a project, a personal project for joy reasons.

Joel: But that's me, I'm an old guy.

Joanna: Is there anything else that people should think about?

Joel: I think workbooks are the first step for many indie authors. Because if you have a non-fiction book, you can have two books to sell instead of one very easily by creating a workbook that will really help people and lead them through the process that you're describing, whatever it is.

A workbook really has to be printed. It is very hard to use a workbook that is just digital, like a PDF or something. That's the way a lot of authors end up going into print.

I've done a lot of workbooks for my clients. But you do have to have some capital or the ability to raise it. You don't have to have it yourself, but if you can do a Kickstarter and really justify your project.

Sometimes people have actually taken in investors. That's usually a family member. We call them investors though.

You have to have some concept of what's going to happen. You have to work it out in advance, Joanna, so you know exactly what's going to happen.

Who's going to print them? What's it going to cost? How are you going to ship them? Who's going to store them? How are you going to fulfill orders?

In my case, I'm not using Amazon. So I have a fulfillment house, and all these journals were not shipped to my garage. I don't want them here.

It was shipped to the fulfillment house, and all the orders go to them. And there's a software integration on the sales page, so they just get the orders and ship them automatically.

You have to work out what the cost for that is. How are you gonna do that? Does that fit in with your profit calculations?

It really probably would be best to talk to somebody who's walked that path already, or a professional, and a print professional of some kind, to really put it all together in a line for you so you actually understand.

Before you actually spend a dollar, you understand what it is that you're doing and how it's gonna work, how you're gonna the orders, etc.?

Now, for most people selling on Amazon, it's probably a really good idea. I tell all my clients that we don't want to deal with returns, missed shipments, damaged books, all of those things that happen when you start shipping physical products.

Joanna: To me, that was the big red flag in the end was to do this I will end up probably not even making any money, and I didn't want to do that.

You're an expert in this. You've been doing this for many years, right, with print products. So, I'm still excited about it in a way. You've really backed up my decision not to do this, but it's fascinating.

What is also fascinating is you started in print specialization. And then, of course, you and I met way back 2009-ish when the indie space was really taking off and digital became the thing. And now this is not going back, but it's going forward. People want beautiful print more.

What are your thoughts on the way that the digital space is changing and beautiful print is kind of resurgent?

Joel: The revenge of print, I guess we could call it. Some of it is perception, Joanna, and some of it is reality.

For instance, if you're an indie author, your perception does not include, and we talked about this, it doesn't include all the books that are being printed on huge printing presses, and bound and shipped all over the world. That is the standard, right?

In the indie author community so much has changed. Think of all the formats we can publish in now. The fact that indie authors can publish paperbacks, hardcover books. They can print on demand. They can do audio books. Nobody could do that 5, 10 years ago, it just wasn't happening. And so you can reach a much larger audience.

A lot of people have really learned publishing. People like you who have really studied it and understand how books are made and marketed are starting to go more into small presses.

I know that's familiar to you, but even people who just got bit by the bug and actually started a real small press on a traditional model where they're buying in books and publishing them for other authors. I think that makes a lot of sense.

There are cooperatives, also the access to the resources you need to publish. Five years ago or eight years ago, if somebody said, “Well, how can I find an editor?” That was like almost a make or break kind of type of thing. It was very hard to find a book editor.

Now we've got marketplaces like Reedsy and BiblioCrunch and these people who'll match you up. It's much easier.

And also another thing that's changed is the acceptance of self-publishing or indie publishing. I write a column now for Publishers Weekly. That's the bible of the publishing industry in the United States. They have a whole section now just devoted to indie publishing.

There's no bigger sign of acceptance that I could think of than we see our titles on bestseller lists, mixed in with all the books from major publishers. So, it's really changed.

Look at the beautiful book that Orna Ross did. I'm sure that was quite a project. I've done things like that. It's not exactly simple.

But I think that the print book universe offers indie authors just a whole multitude of products and formats and things that you can't do in print on demand.

All of those genres where e-books really aren't that big a factor, like if you're not a romance, or a sci-fi, or a thriller writer you really have to look at your publishing business a little differently. Because for those people, it makes sense to go digital, keep your costs low, learn about publishing by going straight to digital, and worry about the whole print universe later.

Once you already know what you're doing. Once you have a project that absolutely has to be a print project or an offset project… And certainly print of demand has expanded a lot.

I'm doing a project for an author now that's a two-volume, hardcover, jacketed reference books that are about 800 pages each. It's from a religious library in Mexico. And then all the buyers are going to be institutional buyers, so the retail price really doesn't matter that much.

But this set may end up going for $150, but they're all going to be bought by librarians basically, or religious institutions. So in that kind of market the whole calculation of the marketing and the production that I was talking about before, to make sure you're doing the right book for your market, changes tremendously when you have a project like that. And this is being self-published.

Books are unique, there's so many different kinds. But people often ask me my opinion about this, and I always say to them, well, you want to know whether you should do with that book, let me see that book and tell me what the plan is.

Some books maybe should be with traditional publishers. I'm not against traditional publishing. 99% of the books on my bookshelf were produced by professionals in a publishing company. We can't lose sight of that.

And if your name is Barrack Obama, you should be with a traditional publisher because they're going to be able to put your book in thousands of bookstores, put you on mass media. But other costs come with that. Other books, you could profitably do yourself.

So it's really a book-by-book decision to me, and then looking to see how we can get that production-marketing mix right so we're producing the right book, pleasing readers, and making a profit at the same time.

Joanna: I don't think Barrack Obama is listening to the show.

Joel: You never know.

Joanna: That would be awesome. It's all fantastic.

I've got the journal here. Everyone can go and check that out.

Where can they check out where the journal is, and also where can people find you online?

Joel: My home online is my blog at thebookdesigner.com. That's thebookdesigner.com, and you can access all my stuff there, including our great interior book templates that are just phenomenally popular and all the other tools and resources we have for indie authors.

The journals live at writewelljournals.com. And right now, we have two choices for you, black or cranberry. Coming soon, we'll have a much-expanded line.

I'm really excited about the positive response I've gotten from people, because they're just really loving using these journals, and that's why I did it. So, even though it's early days and we're just getting started, I kinda feel like I already won.

Joanna: I think we've all won, and I really appreciate you coming on today. Thanks so much for your time, Joel. That was great.

Joel: It's been an absolute pleasure, Joanna. Thanks for having me.

I started a bullet journal recently just for writing. It’s been very helpful to me to have some kind of accountability about how much I’m writing. Even when I forget to use it, I enjoy looking back on what I was working on each day. I highly rec’ iti to any writer. I also love the bullet journal format – so easy to use and can be totally customized for the lazy writer or the artist. 🙂

This was great. I looked into creating a journal to sell as well. I too, think having one that opens flat for ease of writing is essential. That’s why I end up buying spiral notebooks sometimes. In the end, I just created a journal on Zazzle with one of our blog banner images but it’s hard to get the price to be reasonable and make a decent profit that way. It’s probably best for giving away if you need some branded swag for an event, although not a cheap way to go.

He lost me at shrink wrapping – in my day job I’m a beach officer, single use plastic is the work of the devil, please don’t shrink wrap books and journals etc for a momentary moment of gratification for the customer. It will just wind up adding to the 8 million tonnes of plastic that goes in to the ocean globally every year. (Shrink wrap, cellophane etc is particularly bad because its hard to recycle, and easily mistaken for jelly fish by sea turtles and birds). Incidentally supposedly 100% biodegradable film takes up to 5 years to degrade in the marine environment

Personally I’d be making a thing about why my premium product isn’t shrink wrapped

Great podcast but it’s awfully hard to actually look at the journal and get information about pricing and shipping etc so have just ordered another Moleskin! Maybe once Joel’s journal is more well known and easy to find I will try again.