Podcast: Download (Duration: 1:06:36 — 54.1MB)

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

How can you write funny characters and make readers laugh with your writing? Plus the importance of long-term thinking and multiple streams of income when it comes to a career in comedy (or any creative field!). Scott Dikkers talks about these things and more in this episode.

In the intro, Draft2Digital announces distribution to library service BorrowBox; a thought experiment on the US Bills to break up Big Tech [Sway Podcast; Politico; Kris Rusch]; Can you really make passive income as an author? [6 Figure Authors]; List of money books; Wanderland on Books and Travel.

Today's podcast sponsor is Findaway Voices, which gives you access to the world's largest network of audiobook sellers and everything you need to create and sell professional audiobooks. Take back your freedom. Choose your price, choose how you sell, choose how you distribute audio. Check it out at FindawayVoices.com.

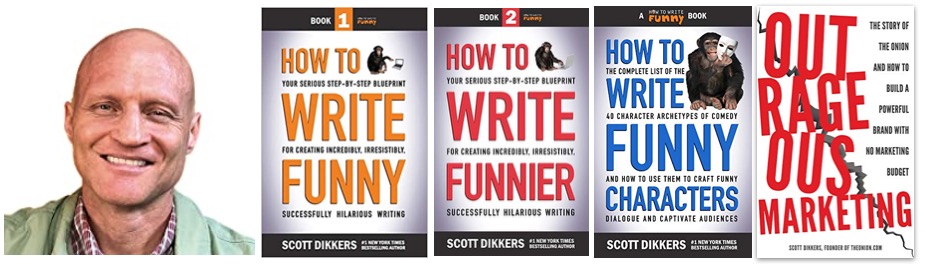

Scott Dikkers is the number one New York Times bestselling author of non-fiction books, including How to Write Funny, How to Write Funny Characters, and Outrageous Marketing, as well as other non-fiction, fiction, and satire. He co-founded The Onion satirical news site, and he's a podcaster, screenwriter, cartoonist, voice actor, speaker, and teacher of comedy writing.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Experiencing failure on the way to success — and the contract that cost Scott a lot of money!

- Why is writing humor difficult?

- What authors get wrong when trying to write humor

- The importance of feedback

- Different approaches to humor and ways to make something funny

- Is humor country or culture-specific?

- Examples of funny character archetypes

- Long term mindset and multiple streams of income

You can find Scott Dikkers at HowToWriteFunny.com and on Twitter @ScottDikkers

Transcript of interview with Scott Dikkers

Joanna: Scott Dikkers is the number one New York Times bestselling author of non-fiction books, including How to Write Funny, How to Write Funny Characters, and Outrageous Marketing, as well as other non-fiction, fiction, and satire. He co-founded ‘The Onion' satirical news site, and he's a podcaster, screenwriter, cartoonist, voice actor, speaker, and teacher of comedy writing. Welcome, Scott.

Scott: It's so nice to be here, Joanna. How can I possibly fit all those things into my life routine? Wonder how I got here.

Joanna: That might be one of my questions! But let's start.

Tell us a bit more about you and how you got into all of this and your creative journey.

Scott: It started very young, before I could read or write. I think I figured out that being funny was a way to get love and attention. And so, I started doing things. I started acting funny and drawing things that were funny and showing them to my grandma, and she loved it.

I got that thing that comedians always talk about where they first performed on stage and got a laugh and they heard it and they were like, ‘That felt amazing. I know what I need to do with my life.'

That happened to me when I was, like, three or four. So, what you do then is you keep doing it, because it's now your strategy for living.

I made little skits on tape recorders, and I made little plays, and I wrote little books. I stapled together pieces of paper and wrote funny stories, and any kind of entertainment, comedy, anything I could possibly think of. Did that throughout my early life in school.

I was the class clown and all that. And then by the time I'm getting out of high school, I know I need to do this for a career somehow. I just had no idea how to do that. My family didn't really have any connections. They didn't have any money. We lived in the middle of nowhere. There was no internet, so you couldn't look up how to do this stuff. And so that's where it all started. But by that time, if you believe that Malcolm Gladwell 10,000 hours thing, I was an expert.

But I will say, my comedy was still terrible at that time. I was not funny at 18 or whatever, and it took a lot more practice to get good at it.

Joanna: How did you go from being an amateur to co-founding ‘The Onion'? I think a lot of people would have heard of ‘The Onion' and then obviously you do all these other things.

Did you ever have a normal job, or did you create this different thing?

Scott: No, I had some normal jobs. I worked at McDonald's fresh out of high school and I did a lot of temp work and I worked at a radio station, and my focus was always on the comedy.

Every spare moment, I was making comedy movies, writing comedy books, drawing comic strips, doing voice acting. But I always had these easy fallback jobs, minimum wage, whatever.

The first thing I got into was voice acting. I just sent a demo tape because I had done all these skits on cassette tape as a kid, and had gotten pretty good at it, and put together a demo tape, sent it to a local studio in Wisconsin, and they said, ‘Oh. We could use an 18-year-old teenage kid for some ads.' And so, they started using me, and then that career blossomed.

I got jobs doing cartoons and commercials, and I was actually on ‘Saturday Night Live.' They did this TV Funhouse cartoon, where I did the voice of George W. Bush. That was very interesting. I did video games. But I was still doing all this other comedy.

Then I did a comic strip, and kept sending comic strips to newspapers and syndicates, trying to get published, having no luck for years, and then finally got a comic strip in the college newspaper where I lived, in Madison, Wisconsin, and that took off and became really popular.

Now I had this second comedy career, or entertainment career, in cartooning, and that became really lucrative because I started self-syndicating the comic strip to other newspapers and I sold t-shirts with the characters on them and made a fortune selling t-shirts.

And there was something about this character… The comic strip was called ‘Jim's Journal', and it was just a stick figure character, but people loved it and you would see people wearing these t-shirts all over campus, and then I sold them at the other campuses where the comic strip ran.

Then I put out a book of the comic, a collection of the first year or two, and that made the New York Times bestseller list, even though I self-published that book. Before Amazon or anything, I'd figured out how to get the UPC symbol, and I had to order away for that, and I had to drive the paste-up boards to a printer. It was very primitive. And so, that was pretty amazing. And then I got a major publishing deal because they noticed me on the bestseller list.

Then, these two guys around Madison, Wisconsin approached me because they wanted to start a humor magazine. I was super impressed with them, and as you can tell from my story so far, I was absolutely obsessed with doing anything comedy-related. So I thought, ‘That sounds like a great idea. Like, something like “Mad Magazine” or “National Lampoon”. Let's do it.'

I jumped in with them and we started doing ‘The Onion'. And that took about eight years of putting it out weekly as a newspaper before anyone noticed it. So it was about the mid-90s by the time the internet came along, and we put the newspaper on a website, and we were the very first humor website, and so we were kind of the only game in town for a while, and grew pretty quickly after that.

We did a book, and that became a big number one New York Times bestseller, our first book, which was called Our Dumb Century, and it was a look back at the 20th century through fake front pages of ‘The Onion', and that led to other books and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. So yeah, that's kind of how that all happened.

Joanna: I love your story because as you said, you worked in McDonald's and these sort of minimum wage things in order to pursue the thing you always wanted to do, which was comedy, and yet you have done so many things.

I love that you have all of these multiple streams of income and you've tried so many things, and some really worked and some took years to work.

I think this is a great lesson for people listening. For me too, I feel like I've been doing writing and self-publishing for almost 15 years, and it definitely takes time to turn your future goal into something.

Scott: Yeah. I've had some spectacular failures.

Joanna: Tell us about some of those.

Scott: One of the biggest ones had to do with that t-shirt contract. I signed a deal with this local t-shirt shop in Madison, Wisconsin to sell those t-shirts, and I did make a lot of money at it, but when I sold my books to a major publisher, it was Universal Press Syndicate.

They're one of the biggest, best publisher of cartoon books in the world. They do the ‘Calvin and Hobbes', ‘The Far Side', they're at the top. They wanted my rights for merchandise so they could sell them nationally, internationally. The little rinky-dink person I was with just could barely get my stuff in these other campuses where the comic strip ran.

I probably lost millions of dollars by not being able to get out of the contract with that t-shirt shop. I didn't know anything about contracts. I didn't even read it. I just signed it and it was literally a 10-year contract that automatically renewed after the first term. So that was big mistake.

Then I started an animation company in the mid 2000s, to make animated cartoons, and that was a spectacular disaster, because I didn't do enough research before going into it. I love making cartoons, I love making animated cartoons, and we made some great stuff, but I quickly realized the only way that you can really survive in that business is to do advertising stuff, which I wasn't really interested in.

Pretty soon I was spending all my time just doing stuff for ads, and I had no time to do the stuff I wanted to do for fun. I was hoping that that could be outsourced and I could step back, but it was so labor-intensive, and the advertisers demanded that I be involved in all the projects, because I was the creative force behind the whole thing.

They didn't want some lackey heading up any creativity that they wanted for their ads. And so it was kind of a breakeven proposition that meant I had to constantly be working on something I hated. And it was really awful.

Joanna: Those are brilliant things you got wrong, signing a contract that locked you in because you didn't think that you would be someone within that decade. So you signed a contract just thinking you would be nobody, really, just making these t-shirts, and then you hit it big, but you had signed your way out of being able to do the bigger things.

That is a great lesson, and a lot of people listening have signed contracts that locked them in, sometimes for the term of copyright.

Scott: Ooh, that's brutal.

Joanna: It is brutal. Well, I reckon I could explore your career for the whole interview, but we need to talk about writing humor. So, let's get into that.

I definitely struggle with this, and I know people listening do, and even, as you said, you started really young, but you still said you weren't funny when you hit 18.

Why is writing humor so difficult, and what are some of the things that authors get wrong when they try to write humor, in particular?

Scott: Great question. There's a few things. The first thing is humor requires originality. So, in almost any other genre, there's a set list of things that work. In horror you need a monster or you need a scary person and they jump out at you or there's suspense, like, ‘Oh, my god, is this person going to get killed or not'?

But in humor, you can't go to some stock list of things that always work, because if you do, you're just doing clichés. And so, it is absolutely the hardest type of writing.

The other thing that makes it difficult, besides that, is that everyone thinks they can do it. Everyone thinks it's easy, because either they're funny or they've made someone laugh before, or they figure, ‘It's humor. I just gotta be a little light and have fun, and it'll work'. And obviously, that's not true because if it were easy, then everybody would be Tina Fey.

So, the real trick for me was feedback. It's about understanding the importance of the audience, because with humor, it only works if it's funny, and you only know if it's going to be funny if an audience finds it funny.

We all have our own individual senses of humor, and sometimes those are really weird, and we can't rely on that, and we also can't rely on just the one person who likes us, our partner, our roommate, our mom, whatever, who's going to read our stuff and say, ‘Oh, I think it's hilarious'.

Then we go out with it and nobody else likes it. You have to have a more scientific process. Stand-up comedians know this because they go out and they do their stuff on stage to a bunch of strangers, and that's the ultimate arbiter of what works. If you can make that group laugh, you know you've got something that works.

So, it's a matter of recreating that in writing. I have a great feedback group that I use, and we're in a Facebook group together, that I run everything by, because even now, I've been doing comedy for 50 years, I still need that feedback, because you don't really know for sure if something's going to work until an audience tells you it's going to work.

Professionals know this, too. On any professional comedy show or any humor novelist who's got a ton of experience, they have to show their stuff to the head writer, the editor, whatever, and they have to let them know, ‘Okay, this is working', or ‘Nah. This isn't working'.

It sometimes can get even harder when you get well-known for it because then people expect you to just nail it without going through that process of getting feedback and improving it. They figure, ‘Oh, he's a genius. He'll just nail it'.

And then that person has a big ego, so they figure, ‘I don't need feedback. I'm just going to make this'. And so they produce something terrible. It's just fraught with so many pitfalls, the whole humor sphere.

Joanna: Even in the writing, if you're in a standup situation, you can see people's responses quite quickly, whereas with writing, you don't have a choice to pause and then give a delivery, or adjust, depending on what you see in front of you. You've fixed it in writing.

Scott: It makes it so difficult. That's one of the really tricky parts about the prose medium, is that not only do you not hear or see the audience's immediate reaction, but you don't know them. You don't know who they are, you don't know where or how they're reading it, so you have no control.

Comedy's all about control. You have to control the audience's perspective, control their experience, and manage their expectations as much as humanly possible. One of the reasons why I wrote this book, How to Write Funny, was because I knew that prose was the most difficult, first of all, humor is the most difficult type of writing, and prose is the most difficult medium to do it in. And I'd done it for so many years at ‘The Onion', and I felt like I really figured it out.

Getting ahead of the game and getting ahead of the eight ball with the audience, and controlling the context, controlling their experience as much as possible, is really the key. Because, like I said, you can't know how they're perceiving it. And because you have so little control, you just have to scrape and fake it as much as you can to control that context.

I'll give you a little hint with an example of how ‘The Onion' does that. So, ‘The Onion' is in the format of a fake newspaper, and that's very deliberate because a newspaper is a very serious, important platform. And so, that creates excellent context for comedy because it's like, ‘Oh, you're not supposed to laugh. This is very important, it's very serious'.

So it gives you that straight person that all comedy needs. And the same thing would be true in a novel where you're trying to do humor. You can't just do fluffy silly humor. You have to have some gravitas, some straight person to contrast with the funny stuff. So, I'll give you an example of that.

Any kind of serious book that just needs a touch of humor, that's pretty easy if you've got a lot of serious stuff going on. But if you're doing a silly, wacky book, where do you find the straight person? A great example is Douglas Adams with The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

There really isn't a serious moment in that story. It's all just goofiness and wackiness, but he has gravitas in the scale of what's happening. The earth is exploding. A guy is taken into outer space, totally unpredictably. And that provides the gravitas where you can now have contrast, and introduce small, silly, light things that create that irony that you need for comedy to work.

Joanna: I think that that is really interesting. I definitely think we are advised in writing to make sure that every story beat is not deep and dark and that having moments of humor or moments of levity is really important.

I would say I struggle with that myself. It's something that I guess I don't feel like I know anything funny or I can make anything funny. So I did want to ask a classic question:

Where do you get your funny ideas, or can we turn any idea into something funny?

Scott: It's a great question. And my joke answer is, oh, I subscribe to ‘Funny Ideas Magazine', and all the funny ideas you need are right there.

There's two ways to approach humor, and that is humor that's played straight, and humor that's played for laughs. When you're playing humor straight, you've got a serious thriller novel or a horror novel, and just need a touch of humor. Then, you have your straight man of the seriousness, and you can just introduce a light moment, and almost any kind of light moment will do because the audience is thirsting for some levity.

I find that to be pretty easy to drop that in a self-deprecating comment from a character, or a silly little thing to contrast with the big things that are happening, so forth.

The other kind is a little more difficult, where it's, like, a light touch, and it's played for laughs.

The way that you get ideas from that and the way that you can make any idea funny is pretty simple. I lay it out in my book, but it starts with subtext. Every joke, every funny line, has to have subtext. It has to have some hidden meaning that you're communicating through the joke, but that you're not actually saying.

That's what you ‘get' when you get a joke. You get the subtext. So if somebody doesn't get a joke, and someone else explains it to them, they're saying what the subtext is. They're saying, ‘Oh, don't you get it? She hates him'. Or, ‘Oh, don't you get it? Politicians are greedy and corrupted'. Words that are not anywhere in the joke.

So the way you make a joke, and you can make a joke about anything, is we all have opinions. We all think things. So all we have to do is write down what our opinions are on any subject.

If you're writing a book, you write down what your opinion is of what's happening in the book. And then, you take that subtext and you run it through this meat grinder that I call the funny filters. There's 11 of them.

There's 11 different ways that you can make something funny. And you can use one or more. The more the better, usually, but you don't want it to be too complicated. You want it to be very accessible and gettable. When that subtext goes through the funny filters, it comes out the other end funny. I'm not going to go through all of 11, though. Just give you some highlights.

Joanna: Just give us one or two.

Scott: I mentioned irony a moment ago. That's one of them, irony. Irony is where the intended meaning is the opposite of the literal meaning. So whatever your opinion is, you state the opposite. And that can often be very funny, especially if it's played straight.

Another one that I think we all know is hyperbole. That's where you take your opinion and you exaggerate it to an absurd or impossible extreme. That makes it funny.

I'll give you one more. A more complicated one is misplaced focus, where you take your opinion and instead of focusing directly on the opinion, you focus on something else that's unimportant or silly, that makes you think of the main opinion. That's how misplaced focus works.

Joanna: I think this is so interesting because what you're talking about, and obviously I've had a look at your books, and there's a lot of work in this, and I almost feel like people think, ‘Oh, if you're funny, you just wake up in the morning and you just write stuff, and it's funny, and you say stuff and it's funny'.

You're almost talking about it in a scientific workman-like way, where you have to work on being funny.

Scott: Surprisingly, it does not come easy. There are some people who do have that, but I don't count on that. I never had that. I had to work at it. And most of the writers I know also still have to work about it.

Now, they might be funny and be confident and sit down and churn out stuff that could be pretty funny, but it's not all going to work. They still have to go through that process of testing it with an audience, and so on and so forth.

And also, anyone who's in that place, where they seem naturally funny, they can just churn out funny stuff, they worked to get there. They practiced for years at doing what I'm talking about, so they've internalized that process of having an opinion and then filtering it through the funny filters and coming out with a joke. So they don't think about it like that, like a science.

Every comedy writer or humor writer that I've spoken to, and I've spoken to a lot on my podcast and just in my life, really digging into this, they all say, ‘Oh, yeah, it's a science. There's a formula'. And we all use the same formula. That's basically how it works, no matter what kind of humor you're writing and no matter what medium you're doing it in.

Joanna: Which is exactly the same as writing a book in general. It's not that magic streams onto the page and you've got a perfect book first time. We all have to work at our craft. So, actually, what you're saying is quite encouraging to me.

My brother has actually just arrived. We've just come out of lockdown here in the UK and I haven't seen him for months. It's just him and me from my parents' marriage, and he's the funny one. So I've always felt not funny, and that I can't be funny. He can effortlessly make people laugh. I feel like I've got a bit of a mindset block around being funny. So, I guess I'm asking for tips.

Can people like me, who feel like they are not funny, can we relax and change our mindset around this type of thing, and add these moments into our books? Or is it something you have to decide on and really work on, as you have?

Scott: A little of both. I definitely think anyone can do it, because I've seen so many people who started with nothing, who just seemed to have a tin ear for humor, really be passionate about wanting to do it, and becoming really great at it, becoming comedy professionals.

I think of it a little bit different doing it in writing versus doing it in person, because in writing, it is really a craft, and it's about crafting jokes, writing a lot of them, and then sifting through those, to pick out the best ones, vetting them with some kind of feedback group. Everybody has to do that. In person, obviously, you can't do that. You're off the cuff and so on and so forth.

The only trick there is confidence. If you have confidence, you're going to be funny. It's just like the magic ingredient.

And I think you know how confidence works. You basically fake it till you make it.

If you walk into a room and pretend you're funny, you're going to say some things that are going to be funny and that are going to work, because people naturally defer and laugh at a person who has unstoppable confidence, especially when they're trying to be funny.

Joanna: I think being British, I have a bit of self-deprecating humor when I speak. I think that that happens.

Actually, that is an interesting question. You've talked about the importance of the audience, obviously, and I love this, because I feel like so many writers write for themselves first, and think about an audience later, but you have to have feedback and you have to think about the audience straight away.

Is there an issue in the international times we live in, where people will self-publish a book or publish a book and it will go out across the world? Whereas is a lot of humor culturally specific, even within a culture? Obviously, you're in the U.S. and you have some interesting politics over there, as you obviously talk about on ‘The Onion'.

Do you have to be really specific about your audience in terms of culture, and country, and all of that?

Scott: No. It's absolutely universal, especially when you're dealing with human beings, because we're all human beings and we all have the same foibles, and our leaders have the same failings. Even if you're doing political satire.

I grew up on ‘Monty Python' and they would do skits about local British politicians who I didn't know from Adam, but they made it universal because they were very smart and very careful about presenting them as basically avatars for any kind of politician, and they had these basic politician characteristics that would work for the humor.

So it didn't matter that I didn't know who they were. And I think that's the way it is for how any book that's trying to be funny can work in a different language.

And you mentioned, the self-deprecating humor of the Brits, that's something I've noticed about you. I think you're very funny in person, and it's surprising to me to hear you say that you don't think you're funny, because, to me, you have a very light and self-deprecating and funny, easy way about the way you speak.

It's probably just a matter of confidence, either in person, or also when you're writing, because you write thrillers and stuff and that, so I think a lot of people who write more serious books or less frivolous, silly books have a harder time thinking, ‘Well, I don't want to be silly, or I don't want to destroy the tone I've got going here or whatever.'

But obviously you've figured out that readers want levity here and there, and it's such a nice rollercoaster ride to have a bit of tension and a bit of excitement, and then have a bit of light touch, and levity, and silliness, or whatever. Maybe not as far as silliness, but at least humor, and then getting back to the seriousness.

Joanna: Let's talk about characters, because you do have a specific book on ‘How to Write Funny Characters', and you mention ‘Monty Python'. I don't know whether it's quite dated now. I think it is pretty dated in terms of some real slapstick type of humor, which is very difficult to do in a book as well, because slapstick is kind of visual comedy.

In How to Write Funny Characters, you have these 40 comedy character archetypes. Now, that is a useful book, people.

Could you just tell us about a couple of your favorite comedy character archetypes?

Scott: Absolutely. So, first of all, I do want to say, I think ‘Monty Python' is as relevant today as it was when it came out. They do a skit called Election Night Special, which is a parody of election returns on a network program. And you could watch that during any election, and it would be totally relatable and hilarious.

They use all 11 of the funny filters that I'm talking about, and one of those 11 funny filters is madcap, which is slapstick humor, silly humor, non-sequitur humor. And you can absolutely do that in writing.

And you should, because when you describe physical action, it's just as funny to the reader as a performer slipping on a banana peel is to a viewer of a movie or a TV show, because we're imagining it in our head. It's no less funny. In fact, it might even be funnier because we're picturing it in the funniest possible way when we do the word picture in our minds.

Let's use that same example for one of my favorite comedy characters among the 40 archetypes. I did identify that there are 40 basic ones, which doesn't mean that somebody couldn't invent a new type of character, but it's always a risk to invent something new because so much of this has been done before, there's no reason to reinvent the wheel.

The only trick is when you use a comedy character archetype, you do have to make it original and fresh, which is really easy to do, and there's tricks and tips for that in the book.

One of my favorite archetypes is the bumbling authority. So that's a character who has some level of authority in society, usually pretty low level, and they're a fool.

We see that all over the place. We see that in Lieutenant Frank Drebin of ‘Police Squad' and ‘The Naked Gun' movies, we see it in Jim Carey's ‘Ace Ventura Private Detective', ‘Paul Blart: Mall Cop', even Basil Fawlty is an example of that, because he's a hotel owner, so he's a very minor authority in society.

And there are so many other examples of that. ‘Daffy Duck' is an example of a bumbling authority. Ralph Kramden. ‘The Onion' is an example of a bumbling authority, because it's a very serious and important voice of news, yet it's foolish.

So, that archetype, people love, because they love seeing authority figures brought down a peg, and it never gets tiresome. Again, the only trick is you have to make it original, and I'll just give you one easy tip on how to do that.

If you just give the character a different type of job or a different species or gender that we haven't seen before or seen much, it'll seem strikingly original. People will feel like, ‘This is such a fresh, original character'. And they won't realize oh, it's just this model of this character that we've seen a million times before. So it's actually pretty easy.

Another one of the 11 funny filters is character. And there was a short section of it in my first book, How to Write Funny, and so many people were asking me about, ‘Wait a minute, how does that work'? And you mentioned archetypes.

So that's what resulted in this new book. It was like a whole book had to be written about just this one funny filter, because there are specific ways that characters need to be used for comedy that's different than how they're used for drama. It's kind of like night and day, the way characters are treated.

Characters in comedy really have to be two-dimensional. They have to be representations of parts of us or different types of people in society, and they can't be taken seriously. So the trick then, if you're doing humor for a more serious work where you do have well-rounded characters, you have to do this thing that Steve Kaplan, this dramaturg who specializes in comedy talks about, where you drop the character.

You allow the character to be two-dimensional for one moment, or one beat, or one scene, where we can laugh at them, because they are now representing a part of us.

Another archetype that I really like that's very popular is the grown-up child. That is, an adult who behaves like a child. They react with far more emotion than a normal person would, given the situation. They stomp their feet and they cry, and they're very immature.

That's a character that Will Ferrell plays in almost every movie. And people love it. People love this character, because it kind of taps into the inner child in all of us. It allows us to laugh at it, yet also relate to it because it is a deep part of us. And so, it's a really powerful comedic character.

You can use that character even if you're doing a serious book, with a serious, well-rounded, three-dimensional character, they can have one scene where they do something childish, and it will be really funny because you're allowing that character to drop momentarily into that archetype.

Joanna: I was thinking about funny characters. There are very few movies that my husband and I will both, you know, find funny, and one of those is ‘Tropic Thunder', which still just makes me laugh. And even now, sort of thinking about it, I'm sure a lot of people have seen it.

They all have various aspects of funny character, and it's about themselves and maybe each one is picking up an archetype, like the one who's a method actor. They all just have these little things that they do.

It is funny, but that some of these movies work really well, whereas I just don't like Ben Stiller's movies in general, but I really liked that one. I don't know what it was about that movie that it actually made it funny to me and my husband, for example.

Scott: Interesting. I did see that. It's been a while, but I definitely remember each one of those characters having a clear archetype.

One way to make archetypes original is to mix and match, combine them, make hybrids is another really amazing thing to do.

I remember distinctly there was one… I forget who it was. There's one character who was the bumbling authority archetype, somebody who's supposed to be very important, like an authority, who is this complete fool. And then you probably had a grown-up child in there.

There was probably a neurotic, which is another very prominent archetype. And because that gives you such great contrast when they're having these international adventures, these military adventures, perfect contrast is to throw in a neurotic, somebody who's nervous, or a nerd archetype, who's nervous and scared and creating a wonderful contrast with all the serious stuff that's happening.

Joanna: Maybe that's the way forward. I think Melissa McCarthy in the U.S. is doing a lot of movies at the moment which were more traditionally male roles, and she's now the funny one doing them. And, again, like you said, even just changing gender can make a big difference. The story's been done before.

Scott: Yeah. Totally makes you feel like it's fresh and original. She did that in ‘Bridesmaids', which was kind of her breakout movie role.

Joanna: Oh, that was a great movie.

Scott: She plays a hybrid archetype of the slob and the lothario, which, we always see those as male characters, and to combine them and put them in a woman felt completely original. And so that was a big breakout for her.

Now everything she does, that spy movie she did, where she was a bumbling authority, where she was a government bureaucrat who had to be a spy, and then she's doing a ton of madcap humor throughout the movie where she's just goofing up and falling and stuff like that.

Joanna: That's a really good tip, actually, is to maybe to find our own original humor is to think about movies or books that we do find funny and then identify why using How to Write Funny Characters and your funny filters.

I feel very encouraged by what you're saying, because it means I can potentially deconstruct things and then reconstruct them in a way that will help my writing, because I feel like this is a weak spot for me and I feel like a lot of people listening will feel this is a weak spot. And as you're saying, sometimes you just have to try these things, don't you?

Scott: Absolutely. I'm the guy in the movie, ‘Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom', after Indiana Jones went through the three tests at the end, with the razor that almost cuts his head off, and then he goes on the breath of God and the path of God and all that stuff, I'm the bad guy who snuck up behind him and deconstructed, ‘Oh, I see. It's a roller, and you just have to duck.'

All my books are is deconstructing humor, laying out exactly the steps for how to do it, and then you can recreate the magic by just going through those same steps.

Joanna: I did want to ask you about another one of your books. You've got lots of books, which is awesome. And you have a book called Outrageous Marketing: How to Build a Powerful Brand with No Marketing Budget. I realize things have changed over your career in terms of marketing and book marketing, but I feel like this bootstrapping approach seems like you've always done, and you've tried different things. How would you suggest authors do this kind of marketing now?

Scott: I think it's the same thing that you suggest, and almost any kind of expert that you would admire in this space would recommend, and that is keep doing it.

Keep putting out books, keep learning, and enjoy the process, because that's really the secret to success.

The last part is so important, enjoy the process. If you're miserable, why are you doing this? But if you like it and you're obsessed with it, so you just keep doing it, you're living the dream. You've won, you've succeeded, because you're doing what you love. And you need to accept that and celebrate that.

Is financial success going to follow that? Well, probably, if you keep it up long enough. And, again, like you said before, it's the long game. Sometimes it does take 10 years for people to get anywhere.

In doing this book, I analyze what I had done to make ‘The Onion' a household name and make it a big comedy brand, and compare that to other really successful companies in a lot of really different fields, like healthcare, and food service, and so on and so forth. And I found the very same story.

It was very surprising to me to compare ‘The Onion' success with the success of the company Walgreens. Do you have Walgreens in the UK?

Joanna: We don't, but I know it's a pharmacy chain.

Scott: Very huge pharmacy chain. And it started in the nineteen teens. One guy, Charles Walgreens, was obsessed with making things convenient for his customers. And he lived that and he enjoyed it. And so he kept doing it. Obviously, there were some setbacks and failures, but he kept doing it.

And then another one is Kentucky Fried Chicken, Colonel Sanders. He was obsessed with making good chicken. And that's what it often comes down to. It's one obsessive person who loves doing what they're doing, who keeps doing it.

That's the secret to doing it without any kind of marketing budget. You become your own ambassador, you're your own marketing. That's the take-home message. People don't have to read the book now, because that's the take-home message of the book, is that it really takes that kind of obsession.

I use that term ‘outrageous' because I realized one of the things that made a lot of these characters that I studied, including myself, being in that clump is they learned how to be the most outrageous version of themselves that they could.

A great example of that is Disney, who's one of the companies that I looked at. A company that was at one time the number one Fortune 500 company for many years, one of the top media companies in the world. It all started with one guy being obsessed with making good quality children's entertainment.

And, so many setbacks, so many hard times, or his brother, who was his business partner, was begging for more loans from more banks so they could keep this foolish crusade going. He was obsessed with making outrageous entertainment, but he had this epiphany where he was always zeroing in on, ‘Okay, what's more outrageous? What's the bigger version of me? What's more me than before'?

So he did ‘Snow White', he did ‘Dumbo'. He did all these really popular movies, but they would make money and then they would stop making money.

And so the company was always operating on fumes. Then he realized, ‘Oh, okay. Maybe instead of just doing funny movies, funny TV shows, I can create a world, a bubble, where kids can go in the bubble and be in the magic world that I'm showing them with their entertainment'. That's like a sharpening, a zeroing in on, ‘What is the unique value proposition I'm offering? How can I make the most outrageous version of that'?

He creates Disneyland, and that becomes the linchpin for the company to really build. Now he's got an actual sustainable, repeatable source of income that is largely responsible for the company becoming as big as it did.

It was a foolhardy venture. He had to mortgage his own house to pay for the first theme park. But it's that principle of figuring out who you are, and trying to be the most heightened version of that that you can, that is kind of the secret sauce.

Joanna: I love that you gave those examples, because it comes back to what we said about your career and the mistake you made about signing a contract without thinking how big you could be in 10 years' time.

So often, people think, ‘Oh, well, you know, I can't possibly be James Patterson or Stephen King'. And, ‘No, we're never going to be that person'. But after years of putting in the work and years of writing books, and like where you are now in your career, is putting in the years of work and that persistence, as well as taking opportunities as they come.

You have to think, ‘If I keep doing this for 20, 30, 40, 50 years, who knows where we're going to be?'

Scott: So much of it is a mindset game, because we can all get depressed about someone who's more successful than us. I think Steven Spielberg is sitting around, grousing about, ‘Oh, that Disney was so much more successful than me'.

Self-doubt is such a huge problem with authors and people in comedy, and there are so many ways to get around that, but for me, one way has always been just to embrace who you are and embrace your own journey and to be happy with what you've achieved.

I'm a huge believer in that hokey saying, ‘Shoot for the moon and even if you miss you're still among the stars', because if you're obsessive and you work a lot, you produce a lot, yeah, maybe you'll never be James Patterson, but you're you, and you've done pretty well, so celebrate that and be happy about that. And there's a lot of people who didn't get that far.

Joanna: I've so enjoyed talking to you.

Where can people find your books and everything you do online?

Scott: Delightful talking to you too, Joanna. I'm at howtowritefunny.com. I've got a ton of free resources there for people who want to get better at writing comedy, free ebooks, and the podcast I do, which is interviews with comedy professionals from all parts of the business, all different media.

If you want to go deeper with me, there's my books, which are all on Amazon and Audible. And if you want to go even deeper, I have courses on how to write humor and how to succeed at creating a comedy brand, and I'm on the regular social media.

If you can spell my name, you can probably find me. Actually, you know what's great? Now, even if you spell my name wrong, I show up on Google, so I'm pretty happy about that.

Joanna: That is great. Well, thanks so much for your time, Scott. That was fantastic.

Scott: It was a delight. Thank you.

Joanna, I value *all* your podcasts. This one in particular will enrich my writing so much. You and Scott helped me identify what’s been missing — that one so-essential, elusive element; humor!

p.s. You are funny, Joanna, in a wry, gentle way which I and all your fans enjoy so much. When I listen to other podcasts, I often think, ‘Oh, I wish this were Joanna Penn. I’d enjoy and get so much more from it.’ No question. So there you are. Thanks for being the amazing Joanna Penn.

Thank you for your kind words, Linda. I’m so glad you enjoyed the show!

Great interview! It reminds me of the phrase used by my lawyer Dad “Couldn’t happen to a nicer chap” whenever he learned about a prominent but shady individual was getting his comeuppance. He was using British irony to express his true thoughts … that the individual was an SOB who deserved everything coming to him.