Podcast: Download (Duration: 58:15 — 47.4MB)

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

How do you know when the seed of an idea is enough for a novel? What makes literary fiction different from other genres? Roz Morris shares her writing process from idea to the publication of Ever Rest.

In the intro, my experience of COVID, my interview on Story of a Storyteller, and A Mouthful of Air poetry podcast.

Today's show is sponsored by ProWritingAid, writing and editing software that goes way beyond just grammar and typo checking. With its detailed reports on how to improve your writing and integration with Scrivener, ProWritingAid will help you improve your book before you send it to an editor, agent or publisher. Check it out for free or get 25% off the premium edition at www.ProWritingAid.com/joanna.

Roz Morris is a best-selling author as a ghost writer and an award nominated author with her own literary novels. She writes writing craft books for authors under the Nail Your Novel brand, and is also an editor, speaker, and writing coach. Today, we're talking about writing literary fiction and Roz's latest novel, Ever Rest.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- The difference between literary fiction and genre fiction

- How to know when an idea is right for exploring in literary fiction

- How Roz incorporates music into her writing process

- Research and preparation before the writing begins

- Revising a book the way music is mixed

- Giving a novel space to breathe while it is evolving

- How do you design a book cover that doesn’t fit into a genre?

You can find Roz Morris at RozMorris.org and on Twitter @Roz_Morris

Transcription of interview with Roz Morris

Joanna: Roz Morris is a best-selling author as a ghost writer and an award nominated author with her own literary novels. She writes writing craft books for authors under the Nail Your Novel brand, and is also an editor, speaker, and writing coach. Today, we're talking about writing literary fiction and Roz's latest novel, Ever Rest.

Welcome back to the show, Roz.

Roz: Hi, Jo. It's great to be back again. I love these shows.

Joanna: We've literally been doing these on and off for over a decade now. You're one of the regulars on the show.

I'm excited to talk about this. So, as I said, you've been on the show a lot. People can go back and listen to your history, so we're just going to dive into the topic. I wanted to start with a definition.

What is literary fiction as compared to genre fiction? And why is it such an emotional question?

Roz: Usually literary fiction is bigger than just the story and the characters. There's usually a sense of universality. The writing is often more nuanced than…maybe sometimes poetic than genre fiction, if we're comparing with the genre fiction.

And if we are comparing it with genre fiction, it might not conform to genre tropes. So if you've got a murder in your book, for instance, in certain kinds of genres it's very clear what must happen about that murder.

In a cozy mystery, it's got to go a certain way. It's all got to be solved and it's got to be put right. In something much darker, it might end with a much darker, more uncertain note. But usually, it would be very clear for each genre what has to happen about that murder.

In literary fiction, almost anything goes. The murder might not be solved at all. And solving murder won't necessarily be the point. It will be something else. So literary fiction doesn't really conform to many genre tropes.

However, this is where it gets quite fuzzy, genre novels might have certain literary qualities. And I think it has a continuum. Each writer might be very genre or very literary or somewhere along the whole rainbow that goes through the middle.

I suppose you could say literary tends to be bigger, deeper, perhaps more mining for individual truths, more enigmatic than just being about the plot and the characters.

And it's an emotional question, as you say, and I think that's because there are all sorts of issues that people might have with literary fiction or non-literary fiction. There's a sense of superiority sometimes one over the other that literature is worthwhile and other kinds of books are ‘entertainment.'

You can hear the air quotes in my voice there. And indeed, you have to think about what entertainment is. These ideas changed drastically over the years anyway. In certain academic circles, Charles Dickens was not taught as literature because he was an entertainer. So tastes change all the time. It really depends what you like..

Another example is that, again, if you talk to literary people about plot, they think that's an absolutely filthy word. And, in fact, some very literary writing courses, I was talking to somebody I'm helping with her novel. She said she's never taught about structure and pace, and she's been on numerous writing courses.

There is just very different values, I think, between certain factions of the writing world. But really, as far as I'm concerned, I write the kind of story that I hope has got great depth as well as entertainment value.

Joanna: I like the idea of the continuum. I think that's really good. And it's that idea of you don't have to be 100% one or the other. For example, I read a lot of horror, and horror suits literary writing very well, I think, because they're so often standalone books.

A lot of literary works are standalone. Would that be right?

Roz: Yes, that's true. Actually, I've never thought of that. But, yes.

Joanna: And the other thing you did say bigger books. And you don't mean bigger in terms of word count because obviously epic fantasy is going to probably be the biggest in terms of word count.

Actually, often, literary books are a lot shorter.

Roz: Yes, that's a good point too. It's not about word count. It's bigger in terms of the scope of the writers' imagination and the scope of the experience they're trying to take you through. It's not the mileage and the number of pages.

Joanna: Now, you are very successful with ghost-written thrillers and you're an official ghost so we don't know the name. But now you're writing your own literary fiction. And obviously, you know how to write these best-selling thrillers.

Why did you decide to not write thrillers under your own name and to write literary fiction?

Roz: Left to my own devices, I wrote what was really me. I could quite easily hit all the notes for a thriller and do the job that was needed. But if I took an idea and was writing it as myself, I just explored what was most interesting to me. And it was always those resonances as well.

Don't get me wrong, I love plot. I love interesting characters. I love the whole pulse of a story that pulls you along and makes you have to know what happens next and you have to stay up and read another chapter. I absolutely love that.

But when I'm writing as me, I just want to get the most meaning as well out of an idea. And that's why I ended up writing literary because it just is the way I think and feel. It's what I'm curious about.

Joanna: It's true to yourself.

Roz: That's right because we all write what interests us and what we're curious about. And that's the wonderful thing about writers no matter what we're writing, it's a very genuine art. We're all writing from a deep place of curiosity and interest.

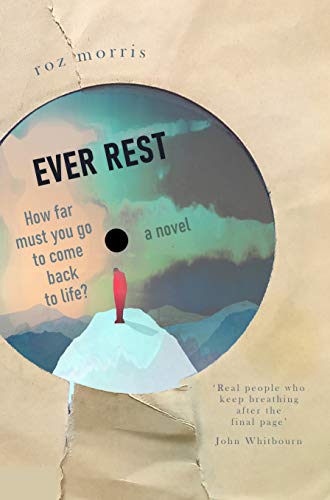

Joanna: For everyone listening, I've read Ever Rest. And it's not Everest, the mountain, although the mountain's in it. It's two words, ‘Ever Rest.' And it's really fantastic work. I've really enjoyed it.

What's interesting is trying to figure out with literary fiction whether an idea is good enough. And like you say, if it's not so much genre tropes, or plot driven, or whatever.

How do you personally identify when an idea is good enough for novel? And how did the story for Ever Rest reveal itself?

Roz: Well, I know an idea is good enough when it just keeps drawing me back. I want to involve myself in it. I want to inhabit it. I want to think about the people who might be involved in it and what they might do.

That in itself just suggests all those deeper resonances, but I will be interested because I'll be thinking, ‘There's something universal here. There's a big truth I want to explore and I want to get at.' So that's how I work out if something has the scope to be I suppose my kind of novel.

It's just because it appeals to my kind of heart, really. And the story of Ever Rest came about because…well, shall I briefly explain what it is?

Joanna: Yes.

Roz: In 1994, a man falls into a glacier when he's climbing Mount Everest and his body can't be retrieved. About 20 years on, he's still in the glacier. And the people who are close to him are still waiting really for him to come out because they can't move on.

The reason they can't move on, what makes it even more difficult than it would naturally be, is that he was one half of a rock band. And it was a world cataclysm and he disappeared and his music keeps him alive for the whole world all the time.

This really appeals to me that the music and the guy being frozen and gradually coming back, and I thought how there's so much in it. It was really powerful to me.

I kept thinking how we all have songs that tell us who we were when we were 19. And we can be that again and it freezes us. And these characters were very young.

When this guy disappeared, they were all involved in a remarkable experience knowing him. It was formative for them. And they're still caught by him. It all needs to come to some kind of resolution before they can, drumroll, Ever Rest.

Joanna: Coming back to the idea, was it that you read an article about bodies frozen on Everest? So that would be one angle. Music's very important to you and we'll come back to music. But did you like, ‘I want to write a book about how music moves people?'

Where was the seed that took you into the story?

Roz: The seed was the mountain. It was the idea of these people being held there. I first had the idea about a man in a glacier. And in fact that there are a few short stories about people falling into glaciers and just being held there.

I thought, ‘Who's waiting for them and what's it like for them?' And pretty soon I was reading about people getting lost on Everest, and I thought, ‘Oh my goodness, Ever Rest. Then it started to come out.

The music idea came a little bit later. But it just struck me one day that music freezes a moment in time. And it often freezes a very emotional moment for you. And so the two came together. I love it when an idea does that, when it suddenly gets a system that fits with it perfectly.

Joanna: Let's just talk about music then for a minute. And you're right, and I think this is true of a lot of people. I still listen to songs that I listened to when I was 15, 16, like you said, 18, 19, where you're at a pretty emotional point in your life and things mean a lot.

I can listen to a song and I'll have that feeling of leaving home or whatever. But now, like, I don't listen to music when I write and now you have this undercover soundtrack on your blog, which shares the music behind people's books.

How does music play a part in your writing process? And how did you use it for Ever Rest?

Roz: It's very, very important to my writing process because the ideas I get are often very emotional. What I'm always trying to do really is pin down an emotion and make the reader feel it. And that's where the nuance of the words I use is very important, the way I describe something, the way I have a character look at another character, all that.

The inspiration usually comes from music. And the music helps me understand what emotion I am aiming to create in the reader.

What I often do is play pieces of music and something will suddenly strike me as, ‘That's the moment when that happens.' Or, ‘That's how this character feels about this.' Or, ‘This is how I want this whole scene to feel.'

I collect these pieces of music that are moments of the book for me and they're an emotional soundtrack. And they let me hold something still because feelings are so slippery and they're so hard to keep a hold of. But music does that for me.

Joanna: That's really interesting. When you're looking for music or listening for music, do you go on Spotify and go a playlist to make me feel nostalgic or whatever? Or is it because you listen to so much music, you'll hear something and go, ‘Yeah, that's that feeling?'

Did you go looking specifically for music that will make you feel emotional?

Roz: I usually start from something that I've already got or I already know. Or I've got albums that I know bits of but not other bits of, and I'll just put them on randomly with headphones while I make notes or while I go for a run.

And then those may lead me to other things. I tend to use YouTube quite a bit and just find videos as well as watching a video of Talk Talk singing one of their songs. And that just gave me a moment the way the guy in Everest would sing something, just watching his face and the emotion that was coming across.

I often like to watch at the same time. And I just go exploring. And yeah, they're often quite random things.

Once when I was ghostwriting I had to write a chase scene, and it wasn't going particularly well. I used music then quite a lot to give me an atmosphere of a place or to actually just keep my bottom in the chair.

If it's not going well, you've got to have something that keeps you there. So I think, ‘Okay, two albums, and then I'm going to have a break.' I was listening to Fatboy Slim. I was writing this chase scene, and it was great because all those cheeky rhythms just gave me the punch that I needed.

So things can be quite random and they can quite randomly be the right thing that you need to listen to.

Joanna: So that's part of the exploring you mentioned and researching emotional side.

What are the other things you do in the beginnings of the writing process in terms of research and preparation before you write?

Roz: A lot of factual research. Ever Rest had several quite chunky subjects that I needed to get to grips with.

There was music recording, which I didn't know that much about, but I was in a band at college and I'm quite musical anyway. Actually I did the music for the trailer with a friend. So I knew some bits about music but I didn't know other bits about the industry.

I went and asked lots of questions to a friend of mine who's a music lawyer. I read lots of books. And they gave me things that could happen that I would never thought of if I hadn't done my research.

Another thing I had to research a lot was mountaineering and the whole landscape of Everest, how you climb it, what the life of climbers is like. I spent a long time soaking up all those facts and the geography.

They gave me some quite poignant things that could happen, some startling facts as well. The landscape of Everest is amazing. It's beautiful. It's very hostile because you get above a certain altitude and you can't really survive. You actually start to die.

And then of course, I discovered that this can be very sensationalized and the mountaineering community are quite sensitive about this and you've got to treat the subject very sensitively especially when you're talking about people being lost.

Those are people. They're not just bodies who are sensation fodder. They are people and they belong to people.

So, again, I found an emotional layer of reality because I had to get in too. I do lots of reading, lots of research, lots of web surfing, watching videos, video casts, all sorts of things.

From that I developed a strong familiarity with the worlds of the characters and the kinds of things that can happen, the kinds of things they might do. And I get a lot of plot ideas from that research as well. It's a very productive process.

Joanna: How are you capturing your ideas and your thoughts?

Do you write handwritten notes or do you type it up or are you just putting things into a plotting spreadsheet as some people do?

Roz: Bits and pieces. I end up with a lot of handwritten notes. And they are scraps of paper torn off things and they become a landscape where I know what a shaped piece of paper I'm looking for on my desk.

I love paper. I love having the actual physical evidence of the thoughts that I'm having. I love having them around me. Then I order them into plot events. And I write cards that have got the events.

If there's a detail that I need to keep, like how something feels or what a place is like, then I have a series of files where I write that down. I might write notes about where to find a really good clip video that shows what something's like so that I can then write it later.

Or I might decide I don't actually need that detail. I'm quite careful about being economical with my efforts. I'll think, ‘If I need this, then that's where to find the detail.' But I might not, certainly there's no point in actually writing it until I'm sure.

Joanna: And then how do you go from there to actually writing the first draft?

Are you a plotter or a discovery writer? And how do you get that first draft done?

Roz: I'm a bit of both. I definitely believe in outlines. So I make an outline.

First of all, I write all the possible events on cards, spread them around, look at them and muse quite a lot. And then I get them into an order that seems to make sense, and write a first draft from that.

Inevitably, some changes happen because once I start to really inhabit the book, things don't go according to plan. So I'm always rejigging the plan to make sure I still know where I'm going. I need to know where I'm going.

I don't mind changing it but if my change has changed the direction, I then do rethink to make sure I don't get lost. And my aim at this point is to get a first draft that I can then delve into and change around.

I don't feel secure until I have a beginning, a middle, and an end. I want all the ends joined with a sequence that roughly makes sense. And then I can really get to work and edit it and pull it apart and enhance things.

Joanna: It's funny that you said really get to work after you finish the first draft. What do you mean by that?

Roz: I did 23 drafts of this book.

Joanna: Okay, to be clear on, what is a draft to you? Because I feel like some people think that means you rewrote the whole thing 23 times.

Roz: Well, I probably rewrote it at least 18 times

Joanna: The whole thing end to end?

Roz: Pretty much or doing extensive changes. Because what I start with is something quite rough and it still doesn't really understand what it wants to be. That's the thing. It's like it's newborn but it needs to learn a lot.

Once I've got that first draft, I feel more comfortable really thinking about the themes and whether I've made the most of them, whether I've made the most out of each plot event. I'll look for repetitions that I do want and repetitions I don't want.

It's as if actually thinking of the book as a music mixing desk, you've got faders, you've got loads of faders, loads of channels and loads of faders. I'll be turning some up, turning some down, muting some, duplicating some. That involves a lot of rewriting.

Every scene really was a lot of scar tissue. That's how deeply I go into the rewriting. But I do regard it as very creative because it's in that work that I get the nuance that I want and the very fine control over what exactly the reader is feeling.

Joanna: So how long then are we talking about?

Give us an idea of how long the research in the first draft and then that editing process?

Roz: You'll be horrified because I first thought of this book about 20 years ago.

Joanna: Well, thinking is fine because we all have ideas. But when did you start I guess really like, ‘This is the book I'm now going to do?'

Roz: 2014. It was a long time ago. Yes. And it wasn't the only thing I was working on. Obviously, during that time, I released a couple of other books.

Joanna: And you've been on the show to talk about your travel memoir since then.

Roz: That's right. Yes, that was an amuse-bouche. That was a temporary break. I needed to let Ever Rest just simmer down for a moment. So I was doing plenty of other work.

But it's the kind of book that needed to mature quite a bit. Other novels of mine haven't taken so long. Lifeform Three was just a couple of years while doing other work again, but Ever Rest was very complex.

I had a lot of characters to put together. It's got about six viewpoints. And they all had to work together in their own ways. And they all had their own voices as well. So there was quite a lot to finesse about it, which is why it took a long time.

Joanna: You mentioned there while doing other work and obviously you're an editor, you have nonfiction, you're a coach, you do all kinds of other things.

Do you think that literary fiction writers or people who want to write a novel of that scope and that amount of time that you're going to dedicate to it, you should really make sure you have other income so that there's no financial pressure on your art?

Roz: That's a really good point. Yes, it really mattered to me to get this book to a state that would really satisfy me. I wanted to be able to take the time. I didn't want to have the pressure to get it out by a certain time. I wanted to be able to take as long as I needed.

So yes, it was essential to have other work that would give me the breathing space. And also this kind of novels I find do very well, if they can have a period where you don't do very much to them for a while.

You come back and you see them afresh. And you see possibilities and also see things that you can get rid of that you didn't do very well. So the long process is quite helpful for getting it right ultimately.

Joanna: Having a bit of distance from it enables you to see more. And of course, as we said, you are an editor and you edit other people's words, other people's books.

How does your editing process for other people differ to your own process? Is it that space that gives you all the distance you need?

Roz: I think I edit other people's work exactly as I would edit my own. I look for possibilities. I'm coaching somebody at the moment, and I'm helping her create an outline for her novel.

I'm looking at the kinds of things that I would look for in my own books. And I also find that it's very illuminating and stimulating to work on somebody else's book. I see possibilities and I can discuss them with them. And I can also see when they've done something I thought that's really interesting, that that's shown how a particular mechanism works.

Because a lot of storytelling is actually hidden mechanisms that effect the reader doesn't know are there. Misdirection, for instance, writers are a bit like conjurers, I think. There's a bit of Derren Brown I think in quite a lot of writers.

We smuggle things past, we hide things in plain sight. And it's so interesting to get a manuscript from someone and have a look at what they're doing and help them do it better and also understand more about your own art from that as well.

Joanna: One of the things I learned from you is the reverse outline.

Roz: Oh, yes.

Joanna: Explain that because that really helps me. I'm a discovery writer, and yet I get to about 30,000 words and then I kind of have to do one of these reverse outline ideas.

Roz: Well, assuming it's my reverse outline you're talking about?

Joanna: I'm sure it is.

Roz: You figure out what your end is going to be and how you're going to get there and just actually plot the scenes backwards. So if they're going to end here, lots got to happen just before then. Well, they've got to get to that point.

So how will they get to that point? There has to be a scene where then this happens. And you build the book walking backwards through it to the point where you've actually left off.

I find that that's quite a good way of breaking through the points where you can't see. What I often find about block is it's not that you don't know, on a big scale, of what to do, but you don't know the little steps to get there. Or there's an objection you haven't yet figured out for yourself. Like, why does somebody do such thing?

Often, that's a really useful thing to sort out. If you find you can't write something, it's because there's a character who's probably saying, ‘I'm not going to do that. I'm really not going to do that unless you give me a better reason.'

Joanna: One of the things that I think is difficult about literary fiction is there are some books that win these literary prizes and they are almost unreadable. It's some kind of, like you say, maybe very overly poetic writing that makes it very hard to read them. And yet, that might be award-winning.

It's just so broad. Like you say, with genre fiction, you know what you're looking for and whether the book delivers on the promise of the genre.

How does a writer know that they are writing a “good” literary novel, when there really seems to be no clear guidelines?

Roz: I think there aren't any clear guidelines, and it all comes down to your own tastes. I try to write the kind of literary novel I would enjoy. And there are plenty that I don't actually. I get lost in the writing, ‘Oh, for heaven's sake, this needs a good slap on the back and a plot.'

Joanna: I think that's why I liked Ever Rest so much because it's plot-y as well as character and lovely writing, etc.

Roz: Oh, thank you. I love plots. I find it difficult because I could noodle around forever with an interesting person and what they're thinking and doing. But when I'm reading, I'm quite impatient. And that's what probably enabled me to write thrillers because I could just get on with them and just get the action going.

With literary, you don't necessarily need that sort of action. But I often explain to writers that action isn't necessarily exciting things happening in a physical sense. It's things like choices and dilemmas and difficult situations. Absolutely anything that keeps our curiosity, it could be action.

I do find that some writers are surprised by this. They haven't thought about action in that way before. And as the literary books that aren't like that, really, everyone has different tastes. We do this for enjoyment. We read for enjoyment, not necessarily to get points or to show off. It's something that we do to fill ourselves. And everyone is different.

Joanna: So if there are no rules really for literary fiction, given that you're an editor and you see a lot of manuscripts, what are some of the red flags? Or what are the things that authors get wrong?

How do we know when we're making mistakes?

Roz: That's a good question. And I always make sure before I work with anybody that our styles are aligned, that we want the same thing. There's no point in me editing a novel that's literary and very experimental, unless I happen to also understand and appreciate that kind of experimentalism. I will steer them wrong.

So, again, this probably comes back to illustrating the point that there are no rules. But what I do is I try to work with people who've got a similar sensibility to me. They want something that's got a story but it's also got the required depth as well.

Then what I find are the biggest problems are how to use the material to keep the reader's attention and to keep their attention on the right things, make them notice the right things.

A lot of people will put in far too much backstory, for instance, or not use it in the right way. So I'm usually telling them, ‘This backstory doesn't belong here. It might work later or you might not need it at all.'

Plot, as I've already said, plot and pacing are our big problems because people often don't seem to think in terms of keeping the reader's curiosity all the time. Once you understand how to do that, you can use your material to keep the reader glued to your book but still have all the depth and the artistry that you want.

Joanna: It's funny, isn't it? And like you say about taste, this is so important. It's something that we always need to keep coming back to. I think what's difficult with literary novels also because they're so standalone is that it's hard to know whether as a reader you might like a literary novel.

And actually, let's come to covers. Because one of the obvious ways that readers pick up books is by the cover and the title. With genre fiction, again, there are things we do that make it very clear.

With literary fiction covers and titles, how do you show the reader with those things what they're going to get?

Roz: Oh, there were long agonies over what the cover of Ever Rest should be like, just what to put on it, to start with.

I had to make sure it didn't look like a genre novel because that would just signal the wrong experience to the reader. As you say, we have to say to the reader, ‘This is this kind of book.'

Typography helps a lot. If you use quite a delicate type face, that tells the reader that it's not a genre novel. If it was a book with a mountain on it, and it's quite big, blocky type, that would say a thriller.

As indies, we have to make the decisions about what clothes that our book is going to wear. And the font and the way it's treated is a really important way to signal that.

Joanna: And we're not going to tell people what the cover looks like. They need to go and look for themselves. But it's very cool.

Roz: Thank you.

Joanna: I think you did a good job with that one.

Let's talk about publishing because obviously you've been working with traditional publishing for a long time as a ghostwriter. You also work as an editor. You indie publish many of your books, your nonfiction and some of your fiction.

What were you thinking around the publication of Ever Rest and why did you go the way you have and maybe explain that choice?

Roz: With all my novels, I've tried, first of all, to pitch them to agents to see if there would be a market for them. Because I always think I'll see what help I could be offered with the book because a publisher who has the right audience could be a big boost for it. They could give it a really good start in life.

So with my previous two novels, I actually did have literary agents for both of them, but they couldn't sell the books. And so I published them myself. I was quite happy with that because I loved the process.

I do love the process of making the editorial decisions and deciding how to present it. And it feels like it's just another piece of creativity I've been able to add to the book.

With Ever Rest I queried agents, and I got some very enthusiastic replies. And then they read it, but they never got back to me. And it was September 2020. I gave them three months.

And I thought, ‘Well, nobody knows what the market's going to be like.' So really, I've exhausted that. I've done as much as I can to find out what's possible for that book as a traditionally published book. So I thought ‘Well, I'll quite happily publish it myself.'

Joanna: Actually, that was fantastic. I hear two opposing things from literary writers. One, there is no point in going indie because it's so hard to market literary books and you'll never sell anything.

And on the other hand, people say, ‘Oh, it's so much better to go indie because traditional publishing never markets literary books and neither do literary fiction authors.' So it's actually much easier to make money as an indie literary fiction author because you can do Amazon ads and no one else is doing them in the genre.

What are your thoughts on marketing and selling literary fiction?

Roz: I think everything you've said is true. But the good thing about going indie is you keep the book alive for as long as you want. And if you go with a press, then there comes a point where they're not as interested in putting effort into it. And it's not surprising because they have to keep producing new stuff.

But you with your much smaller pool of books, if they're literary like mine and they've taken a really long time like mine have, they are very important works to you. And you can keep nurturing them.

I don't necessarily expect to make a lot of money from publishing literary fiction, but what I expect to be able to do is to create my honest art.

And that's why I really take my time with them.

I don't want to be pressured to meet certain deadlines, get them out by a certain time. I want them to be right. And then I will slowly discover the right way to reach an audience.

I think it's very important to find ways of reaching out to audiences. And the way I like to do that is through my blog and my newsletter. And in fact, you told me years ago to start a newsletter, and for years, I thought, ‘What will I put in a newsletter?'

But I started over the last few years to really enjoy writing the newsletters because they are like a way of really reaching out to and connecting with people and people write back to me and that's lovely.

Joanna: I'm a subscriber to your newsletter. I always enjoy reading it, and you get pictures of you with your horse and various other things you're up to.

Roz: I actually don't find it a chore. This is something I hear from a lot of people that writing newsletters is a chore. I used to think that when I thought I had to find news, like, ‘Oh, I'm doing a signing,' or ‘I'm releasing another book,' and so on. But there are certain writers whose production is just not like that.

We are creative people, we're creative 100% of the time, even when we're asleep. So we can write about that. And once I realized that I could do that, then I started to think I will just share things about being a creative person as I would with anyone I was talking to who was interested in talking to creative people. So I now really enjoy doing it.

Joanna: That's great. And last question, obviously, as you said this has taken many years, it's a big project. You've put so much in and it's very important to you.

How do you then go from the finishing energy of one book that's been such work to even considering another book?

Because I often feel, and I don't take as long as you, but I write more genre books, is whenever I finish a novel, I'm like, ‘I'm never writing another novel.'

I really do feel like I've emptied myself and there's nothing left. And then I have to go fill myself up again in order to write another book. But there are ways of shortcutting that process obviously.

How does it feel after such a big book? And how will you get yourself back in the state to write something else?

Roz: You're right, I feel emptied. I also really miss the characters. Sometimes I just go and listen to some of the undercover soundtrack I made for the book so that I can be with them again, because they don't need me anymore but I still kind of need them.

You have to give it time. As you said, refill the well. I think you have to get to a stage where you're starting to look at new things and extract yourself from that book. And start getting interested in other things, in other kinds of characters. You've got to get curious, actively curious about something new.

It seems impossible at the time. It's probably like a breakup with a partner. You think, ‘Oh, no, I just want to really have the same and all the good bits and not have to uproot and start something completely afresh.' But you do have to just read new things, watch new things, try new things.

Eventually the curiosity awakens again in something new. You've got to extract yourself from the way you were thinking for the book you've finished and be able to kind of start living in a new one.

Joanna: Absolutely. Right. So we are out of time.

Why don't you tell people about some of your books for writers and what they can find at your website and where that is and everything?

Roz: I've got a series called ‘Nail Your Novel.' There are four books. One is a process book. One is workbook. One is about plot and one's about characters.

If you are struggling with plot, my plot book will explain all the things you need to do to write plot without compromising your literary credentials. And I have a blog called nailyournovel.com. And you can also find me…I have a website called rozmorris.org.

Joanna: Fantastic. Well, thanks so much for your time, Roz. That was great.

Roz: Thanks, Joanna.

A fascinating listen.

Thank you and well done, Joanna and Roz.

Thank you, Nick!

Really sorry to hear you’ve got Covid. We think we’re doing all the right things but it’s a cunning beastie. I’m a big fan of the podcast, and I’ve read several of your books. Just wanted to wish you well. Get plenty of rest and take care of yourself. Best wishes, Susan

Hello Joanna and Roz,

I listen to this episode today. Glad to hear you are recovering from COVID, Joanna. Get well soon. I really enjoyed this episode and discussion about literary fiction. I agree with Roz when she discussed how blurred the lines are between literary and genre fiction. Writers like David Mitchell, Michael Chabon, and Emily St. John Mandel have used genre techniques in their fiction. While genre writers like Ursula Le Guin, Robert Silverberg, Louise Penny, & P.D. James have used literary techniques in their works. I believe the division is from an old school publishing perspective and doesn’t really matter to serious readers. I read for story and enjoy both literary and genre fiction that can deliver on my need for story. Good podcast.

And I just bought Ever Rest and looking forward to reading it!

Thank you, Marion! And what a good point you make – that the distinctions are less important to readers than they are to the people who must put our work into pigeonholes. Writers’ minds and hearts are much bigger than those divisions – and so, thankfully are the minds and hearts of readers.

Sad to hear you got sick JP. I look forward to your new episodes every week and have listened to almost everything in your back catalogue. You inspire me. Wishing you a speedy recovery.

Thanks, Kristy, I am definitely on the mend. I’m so glad you enjoy the show!