Podcast: Download (Duration: 1:08:58 — 55.4MB)

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

How can we build a creative life based on following our curiosity? What are some important attitudes to hold that will help us with a sustainable life and career? Kevin Kelly shares some Excellent Advice for Living.

In the intro, author newsletter tips [BookBub]; Mark Dawson's 20+ year writing journey; Thoughts on 20Books Seville and London Book Fair with me and Orna Ross [Ask ALLi]; HarperCollins is testing AI-generated content, reported by Jane Friedman [The Hotsheet].

Today's show is sponsored by ProWritingAid, writing and editing software that goes way beyond just grammar and typo checking. With its detailed reports on how to improve your writing and integration with Scrivener, ProWritingAid will help you improve your book before you send it to an editor, agent or publisher. Check it out for free or get 25% off the premium edition at www.ProWritingAid.com/joanna

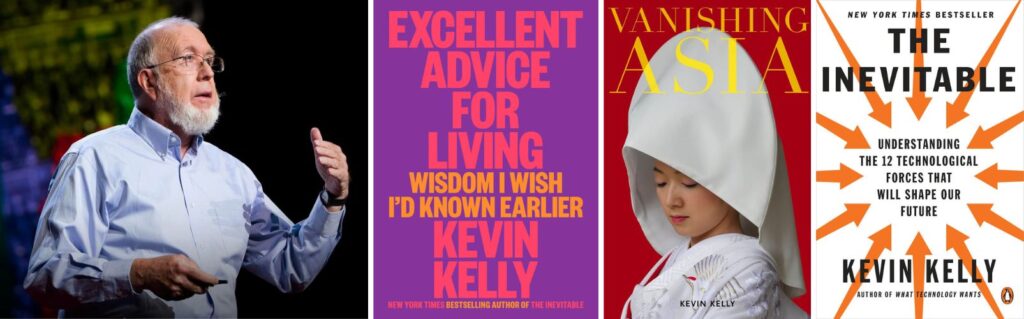

Kevin Kelly is the New York Times bestselling author of multiple books, including The Inevitable, Cool Tools, and Vanishing Asia, as well as being a Technologist Senior Maverick at Wired Magazine and co-chair of the Long Now Foundation. His latest book Excellent Advice for Living: Wisdom I Wish I'd Known Earlier.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Following your curiosity for an interesting, long-term, project-based career

- Experiencing different cultures and the creative process

- Creating art as “imperfect beings”

- Letting your author voice emerge instead of finding it

- Reasons for optimism for writers with generative AI

- Why 1000 true fans is still relevant

You can find Kevin Kelly at KK.org or on socials @Kevin2Kelly

Header image generated by Joanna Penn on Midjourney.

Transcript of Interview with Kevin Kelly

Joanna: Kevin Kelly is the New York Times bestselling author of multiple books, including The Inevitable, Cool Tools, and Vanishing Asia, as well as being a Technologist Senior Maverick at Wired Magazine and co-chair of the Long Now Foundation. His latest book Excellent Advice for Living: Wisdom I Wish I'd Known Earlier. So welcome to the show, Kevin.

Kevin: Oh, I'm really delighted to be here. I really appreciate you inviting me. Thank you.

Joanna: Oh, no, I'm excited. And there is indeed a lot of excellent advice in the book. So I've pulled out some particular quotes for writers to explore further. And the first is:

“Draw to discover what you see. Write to discover what you think.”

What part has visual art and writing played in your life? How do you balance creation with consumption?

Kevin: That's a great question. I, for some reason, have been a maker, which is what we call it now, all my life. I didn't call it that when I was growing up, I was just a kid who liked to make things, and not just little things, but larger things. So I made a model train layout with plywood with, you know, a little city and lights and things when I was probably 10ish, maybe.

Then I went on to make a nature museum when I was 12. I found a book at the library about how to make a nature museum. And I was doing collections and making exhibits, and I went on to make other things like that. I don't know, it was just something in me that wanted to make stuff.

I got into art as a kid, and I almost went to art school after high school, which I should have done, but I didn't. So it's always been a part of how I see things. I eventually kind of gravitated to photography because it was a combination of my other love, which was science. So it's kind of technical and art at the same time. And when I started, you had to do the chemistry, and go into the darkroom, and do the magic chemistry, and so it's very technical. And that was very much a part of me.

I would go out to photograph to see. I mean, there was something about doing the art that enabled me to see things. Partly, it was an excuse to see it, and partly, it was that act of trying to look and see. Then when I was drawing, I realized that most of the effort was actually to see the thing. It wasn't the hand, it was your eye trying to see something, and then you could transfer it to your hand.

Later on, when I started to write, it was the same thing. I don't have an idea, and then I try to express it. It's quite the opposite.

I don't even know what I'm thinking. I don't know what my idea is until I try and write something, and that act of writing it kind of puts the idea into my head.

It's very weird. It's sort of like I try to think what I know, and I realize I don't know, and I try to get somewhere. And that act of trying to write actually creates the idea, so that's what I meant by that.

Joanna: Well, we call that discovery writing. That's what we call it.

Kevin: I'm a discovery writer. Okay, I didn't know that. Thank you.

Joanna: Some people in the writing community call them ‘pantsers.' And that is a very American word, obviously, because in England, pants is underwear. So we kind of adopted the word ‘discovery writer,' because you know, that's better than pants.

Kevin: I don't get the pants reference.

Joanna: Writing by the seat of your pants.

Kevin: Ah, okay. I think discovery writing is more apt. That is definitely my style of writing. I don't write as much fiction, but I would even imagine I'd probably do the same when I write fiction.

Joanna: Oh, good. It's interesting, because you talk there about almost changing your process over the years and changing the way you see and you learn to write by writing and figure out what you think. But I wondered how your writing process, in particular, has changed over the years because you've written some very different types of books.

Like The Inevitable, I've got it here in hardback, and I quote it often. It's about technology, it's about art as well, but it is mainly about technology. And then Vanishing Asia, of course, is a photo book. And I wondered, how has your writing process changed?

How do you decide on what book to write next because they're so diverse?

Kevin: Yes, you're absolutely correct. The Vanishing Asia book, which you mentioned, does have 9000 captions. There are some words, even though there are 9000 images as well, but that was a matter of, you know, its labeling rather than creative writing. Although I had to condense a lot of information about a picture into a few words.

I tend to write telegraphic, and as I've gone on it's become more important to me. That's one of the things happening with this Excellent Advice book, which was me trying to make it as telegraphic as possible. I somehow enjoy that process of trying to distill something down to as few possible words. I don't know whether that was my background editing.

I'm a more natural editor than a writer, let me put it that way. My natural tendency is to edit. I'm comfortable editing. I am just in pain trying to write that first draft, and it's just excruciating.

I work with writers. So I work with writers who love to write.

I don't love to write, I love to have written. And so I'm much more comfortable in that kind of distilling something down and removing words, rather than adding words or making up words.

Over time, I'm not sure how I would say it's changed. So maybe, one, is that kind of appreciating the distillation process. It's a piece of advice which I put into the book, which is this idea that all professional writers get to where you have to generate lots of bad stuff, first drafts that you're going to throw away, but know that. And I didn't know that in the beginning. I didn't realize that you would do that.

That seemed kind of like a waste, or a failure or something, that you would generate stuff that you would throw away, knowing that you're going to throw it away. I mean, that's the difference. And so now I understand that I'm just going to write a whole bunch of stuff that I'm just never going to use, and that's sort of the point of it.

That took me a long time to understand that. And that's true for anything I make now. I just assume I'm going to get there by making prototypes, going to make different versions of it as I go along, knowing that I'm not going to save the initial ones, that I'm not going to hold on to them. That changed over time where I understood that. So it's much more about the process now, rather than about the artifact.

Joanna: And with your photography, because I mean, you started taking pictures in Asia decades ago when digital photography was not as it is now. So now you can take millions of photos and then spend the time editing, but originally, you would have had to take fewer photos, I guess.

So is that maybe part of why your process has changed because you do have this abundance? And that must make editing also a lot harder.

Kevin: You're absolutely right. So when I started off 50 years ago, 1972, photographing in Taiwan, Japan, and I had precious rolls of film, which had 36 exposures in a roll. And the cost of that developing and buying the film, in today's dollars, is about $5. So imagine each time you clicked your camera phone it was $5. That really tends to focus what you're going to shoot at.

So that habit of really trying to sort of edit in the camera, they were calling it, where you spent much more time thinking and moving about and pretending you're photographing, but not actually photographing, that kind of slows you down.

And that habit, I still maintained even as I went to digital of trying not to take a lot, and really trying this decisive moment idea of like waiting for the right moment and then taking as few as possible.

I'm not the auto motor. There's a motor-driven mode in a lot of cameras where you just ‘click, click, click' and then later on you pick out the one that you like.

I'm still much more trying to time it myself, kind of like as if it was film. So I think it's true, that model of trying to minimize the things and trying to edit in the camera as much as possible, is an old school version. There's really no reason not to take a lot of pictures, they are all free. But to me, there's a different joy in it.

Joanna: And then just staying on Asia, because another quote from the book says:

“Expand your mind by thinking with your feet on a walk, or with your hand in a notebook. Think outside your brain.”

Which I really love. So how have your travels in Asia, in particular, being so many different cultures, helped you think outside your brain? How has Asia changed you?

Kevin: Well, the way that Asia changed me, I mean, it's just so immense, it would be an entire book in itself. Because I went to Asia from when I was very, very young, I was 20, and I had never been outside of New Jersey, New York and Massachusetts. And in the 70s, early 70s and 60s when I was growing up, it was a very, very different world, a very different America, and I had never eaten Chinese food in my life. I had never held chopsticks in my life. It was a very parochial world.

So going and winding up in Taiwan in 1972, it blew my mind. It just was so utterly different from anything I experienced in suburban New Jersey. And there was an openness, meaning that everybody was working out on the streets, so everything was visible, their sense of privacy was very different. You could kind of walk into anything without any objection, or people will be welcoming. People did things differently. It was just mind-bogglingly different for me.

That was the beginning of it, and I just kind of went on to most of the Asian countries from there, photographing, but also learning. I mean, after I was done, I awarded myself an honorary degree in Asian studies because there was so much. And the diversity within Asia is much greater than even from any Asian country to America, really. It's just huge. From Turkey, to Japan, Siberia in the North, down to Indonesia. It's just vast.

So I learned from those things, primarily, this idea of the benefit of otherness, of having differences, of thinking different, and having a different way of doing things.

Because we are now in a world where we're connected all the time with each other 24 hours a day. And yet, the engine of all the innovation, and even the wealth, is coming from being able to think different.

It's harder to think different when we're connected together. And I find that traveling, it being physical, having those hurdles that your body has, and being outside of your head and actually immersed in the world, and using your hands to do things, it ignites different ideas. It ignites ideas that you can't get just by thinking about things.

This is one of the reasons why I preach embracing technologies is because we can think about what these technologies are going to do, but we have to use them and do them in order to actually see what they're good for and know what they're not good for.

So engaging in the physical world is the ultimate trip, and it's the ultimate way to make something happen. And it's the ultimate way to learn and to understand what's happening. So I think the value of travel, we should subsidize it to the youth because it is so so valuable.

Joanna: Yes, I have another podcast called Books and Travel, and it's definitely one of my obsessions. I was wondering whether you have — this is something I struggle with, which is being at home. In that when I'm home, I am always planning my next trip. And so whether wanderlust is just part of us as a character, our innate, and that's just from curiosity, or whether you think you'll ever stop traveling?

Have you found ‘home' or is your home everywhere?

Kevin: Well, I was shocked, utterly shocked by COVID because for two and a half years, I did not travel anywhere. And I mean, I was a rolling stone until that point.

And the shocking thing was I did not miss it at all. It was like if I never got on a plane again, I'm perfectly happy. It was so weird because I would not have ever predicted that. I haven't actually gotten back to the level of wanderlust. And so it turned out that I was happy not traveling.

I didn't hate it, it wasn't that I was burned out, it was just like, oh, okay, well, can't travel, that's alright, we'll make stuff at home. And so that was something surprising that I did not know about myself, which was that I was going to be happy not traveling.

I've picked up again, a little bit, but not as much as anywhere near what I was doing. And it's been fine. So I don't know what that says. I'm not, as you know, as obsessed with finding these little corners of the world that are special. I'm maybe figuring that I've done a lot of that, and it's okay. And now I'm kind of doing other things. So for me, that was a surprise for myself.

Joanna: Was that at the time you were doing the Vanishing Asia books?

Kevin: Yes. Yeah.

Joanna: So maybe with that, you were kind of virtually traveling every day because that was such a huge project.

Kevin: Yes, yeah. I had a half a million images that I was going through and editing. And I did the layout and design for all 1080 pages. Each page has a different design and I had to color process, or you know, basically touch up every single one of those 9000 images. Yeah, there was a huge amount of work.

So yeah, I could have been satisfied, my wanderlust could have been satisfied by reviewing all these images, some of which were taken almost 50 years ago. So that could have been a large part of it.

Joanna: It's interesting. And then I wanted to ask, another quote that I really liked was:

“Only imperfect beings can make art because art begins in what is broken.”

And that really made me stop and think. So how has being broken impacted your art?

Kevin: As I said, superheroes and saints don't really make art. Mother Teresa, Jesus, they weren't doing art because there was nothing to complete. So it's our incompleteness. It's our kind of search for things, this yearning to restore something in some ways, that I think is this fundamental thing of making the art, the expression.

My definition of art, there's lots of definitions, but mine is cool and useless. It's things that we make that really aren't practical in that first-order sense. They're kind of existing just because, and that sense of that they're there for us, the primary audience is ourselves.

So there's a question that we have that we're kind of answering. And we may not even know what the question is, but we're making an answer to it. And so if you don't have questions to yourself, if you're perfect, you don't have questions about yourself.

And so the art is kind of a way of trying to answer a question that you're not even sure what it is. And for me, that's what it is. It's kind of my inner self talking to my conscious self, or making itself conscious and aware. And so there's a lot of subterranean work going on because I'm imperfect, and I see the same in other people as well.

Joanna: Well, it's interesting, you say subterranean. I mean—

Do we even know what it is that is broken in ourselves when we make our art?

Kevin: We often don't know. My basic stance is that we are totally opaque to ourselves. We don't have great access to our own inner self, how our minds work and why our minds work. Some people use dreams and other things to try and access that, or therapy, and art is certainly in that same category. And we use other people's around us to help us understand ourselves.

I mean, even on a kind of a scientific level, we don't understand how we work very well. We don't understand how our minds actually work. And so this is another tool in trying to access our inner workings and what makes us tick. And if we're lucky, maybe by the end of our life we have a slightly better idea than when we began.

Joanna: Yeah, hopefully. Well, it's funny because there's kind of an obsession in the writing community about finding your author voice.

From what you're saying there, it's potentially we might never really find it, but that it might emerge.

Kevin: Well, so I have some other advice in the book about kind of the journey, which I think is close to last week, which is like basically, your goal is to be able to say on the day before you die, that you fully become yourself.

So we want to kind of like become all that we can be, we want to become what is possible, what we're kind of arranged to be, all the talents and geniuses that we have. Everybody's is different, like we have a different face, we have a little slightly different arrangement to things.

For me, my goal is then to try and, another piece of advice in the book, not be the best, but be the only. And that is kind of coming to where you are doing something that only you can do, and that's a very high bar.

It's a very high bar because it requires some kind of self-knowledge and knowing what you are better at than most people or any other people.

For most of us, that will take all our lives. It will take all our lives to get to the point where we have a grasp of what it is that we do much better, if not better, than anybody. And there may be some people who are prodigies, who very early in life can see and know themselves well enough that they know what it is that they can do better than anybody else, but most of us, it's going to take a long time.

So it's a process, so it's never done. That's another piece of advice. Like basically, you're getting lessons all your life, and if you're still alive there's another lesson to come.

I don't see our lives having destinations, I see these as journeys, and we're always going to be working on it. And if you're alive, you're still trying to become yourself.

So it's a direction. I think that that's one of the reasons why I say, another piece of advice from the book, is that when you're starting out, it doesn't really matter where you start. Particularly for young people, don't get too hung up on your first job or your major or anything, because it's very, very, very rare that anybody stops or ends up where they started.

Most of the remarkable lives that you would admire, people that you might respect, heroes that you have, they started somewhere way, way, way far from where they from where they are.

And any remarkable person's life is meandering, full of detours, and setbacks, and sharp turns. So it doesn't really matter where you begin, as long as you're kind of going in a direction and making progress, in the sense of becoming more of who you are.

So that's my advice to young people is just master something. You've got to master something, that's the platform. But it doesn't really matter too much where you start.

Joanna: And it's interesting, again, looking at everything you've created as a maker. And the things you've started, in many ways, they're not related in some way. I find that fascinating.

Does curiosity drive everything you do?

Kevin: Yeah, I'm always trying to surprise myself. So I did a piece of daily art every day for a year, I used Procreate and made and painted and drew a piece of art every day, and it's on Instagram, and Twitter, or on my website. If you look at them, it's like, there's no style, no theme. I would try and surprise myself.

So I would sit down, and like I would have literally no idea what I'm going to draw today. Then I would like to try and get an idea. I wanted to surprise myself with something that I didn't know how to me.

So my projects are a little bit like that too, where I guess I do have a fear of repeating myself. But that's really mild, it's more of understanding that there's so much to explore and trying to use each opportunity to draw as opportunity to learn. So I'd say, oh maybe today, oh, I had this idea of a map, I'll try to make maps. I don't know much about maps, so I'm going to learn. You know, so I'm going to be learning about how to make a map as I try to make a map.

So that's why I'm a total addict for YouTube because this is the learning machine. So my art for me is learning about the world, learning about myself. And I try to keep moving in different kinds of projects to maximize and optimize my learning.

Joanna: It's interesting, given your different projects, and as I said, I've been following your work really since 2006, 2008, around the 1000 True Fans post. And I've always been like, wow, that's a completely different project.

And in this author community, a lot of the listeners, we do have to kind of please certain people. And you've got these books, but one of the tips in the book is:

“If you can avoid seeking the approval of others, your power is limitless.”

And I read it and I was like, well, that's great, but as authors, we need approval from agents, editors, publishers, readers, critics. So how do we put that need for approval aside to just create these things that we want to create?

Kevin: Yeah, it's a weird balancing act, this work, particularly the work of authors, but works of artists and creators. It is a really weird balancing act between ignoring what everybody else says and paying very close attention to what everybody else says.

The reason why we have people in our lives, family, friends, customers, readers, clients, colleagues, is to help us see who we're becoming before we are, to help us to see who we are, because it's impossible for us to do this journey alone.

As I said, we're just so opaque to ourselves. We need others around us, including readers and publishers, to help us see, to understand, because we cannot understand ourselves by ourselves. There's a little kind of recursive loop that you get caught up in, so you need that outside perspective all the time. But we don't want it to be binding, to imprison us, to prevent us from moving or progressing.

So there's this weird thing, I think it said somewhere else in the book that you need three things to really create something really great, which is the ability to never give up. And secondly, the ability to give up when it's time to give up and move on. And then your friends and family around you to help you discern the difference between those two modes.

So there is this sort of inherent paradox in creating where you want to use the feedback and the signals you're getting from readers or publishers. At the same time, you have to be willing to ignore those at certain times. And it's that art of making those compromises.

You're not always going to get it right, and that's, again, another piece of advice about why, if you're going to be creative, you have to do it iteratively.

You have to do it on an ongoing basis, you have to do it lots of times, because you're not going to get that mix right. Sometimes you're going to be incorrect and wrong about ignoring what people say. And other times you're going to be wrong by paying attention to what they're saying. So that's the value of professionals and others who do this on an ongoing basis because you can keep trying, and over time, you'll get that balance correct.

Joanna: Yeah, it's really hard. I guess it's seeking approval after you've already made it, as opposed to during the making of it.

Kevin: I think you put it very, very well. So yeah, while you're making it, you don't want the editor or anybody around making judgment. And then once you've made it, you may abandon it as well, which is fine, because that's part of the process. And then at that point, yeah, you don't care.

There's another bit of advice, too, which was when someone is telling you that something is wrong, they're usually right, but when they're telling you how to fix it, they're usually wrong.

Joanna: Unless they're an editor, of course.

Kevin: Well, yes. I have a maxim to myself, which is the editor is always right. And I believe that both as an editor and as a writer, is that I generally will follow the advice of the editor. Very rarely will I just insist and push back.

But generally, my default mode is the editor is right because I value that outside perspective . You want to find someone you trust, but they can be incredibly helpful. And of course, while I was editing, I believed the editor was right. So yeah.

Joanna: Yeah, that's great. And I think it is about finding people who you trust to listen to, which I love.

I want to move on to the AI stuff that's going on because you actually wrote a piece in the last Wired Magazine about generative AI. And you're now posting AI-generated art on Instagram and Twitter @kevin2kelly, and I've got you on my feed, so I have a look at that.

One of your pieces of advice is: “Don't bother fighting the old, just build the new.” Which I thought was great.

What are you enjoying about this AI-generative art phase in technology?

Kevin: Well, partly I'm exploring. If anybody sees the feed, they'll see like every day, it's like, again, I'm trying to surprise myself. Like, I'm just trying to do something weird and different and take advantage of the fact that my drawing skills are very limited.

And here's this machine that can do tremendous drawing, so what can I do if I've been able to amplify my abilities to render things. So it's mostly exploring to see what is capable.

I get pleasure out of the images. And this was one of the things that I kind of realized, working on Midjourney or something, is that most of the images being created, have an audience of one. It's like having your own little museum and you're just seeing the beauty of these images. It's like, wow, I just really enjoyed it. And that's simply just to see them. No one else may ever see these again, but that's the genius of this thing is it doesn't matter.

I just get the pleasure of seeing these cool images. And they do take time to generate, and they almost take as much time as if I was really good drawing and I was drawing them, to get a really good one. You can get any image instantly within seconds, but to get a really, really good one that you just kind of want to stare at, and look at, and enjoy, it will take up to half an hour.

So I'm learning that process. It's a little bit like photography. You know, the painters in the 1800s were very concerned about photographers because they said all you do is push the button.

Anybody who's a photographer knows that photography is not just pushing the button. There are a whole lot of other things that go on to make a really great photograph. That's the same thing we're finding about AI art.

It's not just clicking, it's like you're a photographer, you're kind of hunting for things, you're moving through this latent space of possible images, hunting for things and looking, and kind of setting it up, and you've got your bird blind, and you're kind of waiting there to see what comes up.

There's this engagement and this sense of hunting for these things and discovering them and kind of co-creating him. That's what I enjoy as well. And that process of, okay, just one more, I think I'm getting close, wait, it's almost there, wait, wait, oh, I got to shift over.

So the process of the creative process is that work as well. And I just enjoy discovering these things and kind of finding a little corner that nobody has ever been to before. That's the thing, you make these little worlds, and you're there, and you're kind of discovering what's in this world. And there's never going to be anybody to go back to that because it's almost impossible to get there again. That's kind of fun.

Joanna: Yes, and I've been having a lot of fun on Midjourney as well. But like you said, you're a photographer, I mean, I do take photos, but I don't consider visual art to be a medium where I'm any kind of expert.

But a lot of people listening, I mean, we now have obviously chat GPT has gone mainstream, but we also use tools like Sudowrite, and there are tools for writing as well. So what are your thoughts—and obviously, this is the beginning, this feels like day one for this kind. And you also say that the future is decided by optimists, so I like your positive spin.

Are there reasons for optimism for writers with this kind of generative AI?

Kevin: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. It's really great. I think right now the current framing for these chat bots, and we'll call these maybe image bots, Midjourney and Dall-E and Stable Diffusion.

So the image bots and chat bots, so these bots, right now the best way to think of them is as the universal intern. They're interns. They're capable of doing a lot of stuff, but you need to check the work. You can't release it by themselves. It's like, it's embarrassing, and people will see it and they'll begin to notice. Already people are becoming very sensitive to say, well that's an AI-generated image, I can just tell.

Also, again, going back to the prose and the writing, is if you don't push the bots, they're going to generate something very, very bland and middle of the road. It's kind of the wisdom of the crowd intelligence. It's based on the average of humans, and so they tend to predict what the next word an average human would say. That's remarkable, and it's useful.

The point is that a lot of this stuff is useful. Summaries, research, suggesting the details of a scene, generating names, maybe a punch line, it's all really great stuff. But it's like the intern doing work, you still need to add your voice, your angle, the bots have problems with continuity, they have very short attention spans. They can do the scene, okay, maybe, but anything longer, they have kind of dream logic at work.

So there's currently just lots and tons of problems, that even though on first draft is kind of amazing, it's the interns report, its interns help.

And I mean, I'm using it all the time, and I have tons of friends who are using these in many different ways as interns. So like they're saying, okay, intern, give me some headlines for this blog post. And the intern will give a bunch of headlines, and there will be one kind of pretty good, and I'll just tweak a little bit.

So that becomes sort of a habit, where you're giving the intern all kinds of stuff, and maybe they're making a first draft that has some points. Or vice versa, you're doing your first draft and sending it to them to proof. I've had some friends who are putting scripts in and saying, “Where are the plot point weaknesses in this?”

It's like having another pair of eyes, another brain working with you.

They will get better, but we will get better at working with them. And I see this as a partnership. Some of these might get big enough that you feel like you have a co-writer, which is great.

And so what we're going to be able to do is actually make the best human written stuff slightly better, and a lot of stuff will be written where there's nothing writing right now. And so that's good, it's like the images.

A lot of the images are being generated for where there is no art being made. It's where they're already blank. I'm using a lot to make pictures for my PowerPoint presentations, or my assistant does her dreams, and every day she creates a dream for her newsletter. And there were no images before, so now there are images, and that's sort of one of the things we're going to do is we're going to have better writing where there was no writing at all, and some of the best can be a little bit better.

Joanna: Well, it's interesting because creation for the sake of creation, which we've talked about, and making our art. But it's interesting, given that you wrote 1000 True Fans back in 2006, whenever it was, and it feels to me like we're back there again. Especially with the mass amount of content that will be created now with generative AI, is that in order to make a living this way, in order for me as an author, to make a living as an author, I still need to come back to my 1000 true fans.

Has 1000 True Fans been true for the last 15 years? Or do you think things have changed?

Kevin: So just to maybe rehash it for those who may not be familiar with it, the idea is that if you, as a creator, and you can be a writer, but you can be a photographer, or sculptor, songwriter, anybody who's creative, you're kind of an individual, and that with the new technologies which have since come along since I first wrote it, like Crowdfunding, Kickstarter, or Patreon, all those kinds of things, and other tools, that with this new technology, you could have direct engagement with your audience.

Then if they were true fans and could give you a certain amount of money per year and you got all the money, you got to keep it all, you didn't have to share it with a label, or publisher, or studio, then you need far less of an audience in size.

You didn't need a million people, you didn't need 100,000, you need something in the 1000s. That would be able to give you a living. If you could get your fans to pay you $100, and you had 1000 true fans, and they were true, crazy, loved everything you did, bought everything you made ever, the hardcover, the softcover, the audible version of it, and you can get $100 directly, then with 1000, you have $100,000. And that was the theory.

When I first proposed it, there was really nobody doing it at the time. But these new tools have come along, and there are tons and tons of people who have a livelihood, a living, not a fortune, but a living, with fans in the thousands.

And I think the technology has continued to make that better, easier, broader. Social media has helped that process because the idea is that if you only 1000 true fans, and let's say your interests, your niche, is one in a million, only one in a million people are going to find the same passion and fascination that you have with some weird thing, maybe it's that you write crime novels for left-handed skateboarders. I don't know, I'm making something up.

So there's one in a million people who really are into that, but with several billion people, that's 1000. That's 1000 potential people in the world who are going to love your stuff. So the hurdle, the challenge, becomes matchmaking, finding them, having you find them and having them find you. And that's where social media has helped in that process. We're still inventing other tools for discovery so that you can find those 1000 true fans and they can find you.

Having said all that, what we also understand is that this option is not for everybody. It's a full-time job, or it's a half-time job. I mean, it's like there's a lot of work tending fans, and true fans, and a lot of creators don't want to do that. They just want to write or they just want to paint and they want to photograph, they don't want to tend fans on social media.

So all right, well, then they would employ publishers and editors and all that kind of stuff. And that's fine, so it's just an option. And there are people who shouldn't be doing that, they're just not cut out. They don't have the personality to interact with fans. So we have other options.

I've always said that this is just a possibility. It's a good place to start. Also, by the way, lots of people will start this way, get going, and realize, hmm, this isn't really what I want to do, but I now have enough visibility that I can transition into something with more of an institutional process, and that's a perfectly fine path as well.

So I think the tools continue to make this option more viable, a better choice, particularly for those who are beginning, and something that can serve more people around the world.

Joanna: Brilliant. You mentioned possibilities, and certainly, I've found that your work has expanded my possibilities over the years. So we're out of time—

Where can people find you and your books online?

Kevin: Thank you for that. My website is my initials, KK.org. On the socials, I'm Kevin2Kelly.

Some of my books are actually posted for free, my first book is completely online, I think my first and second books are there. I have a newsletter every week called Recomendo, where we recommend six cool things. All kinds of stuff to read, to watch, to go to, to use. It's free, called Recomendo.

So yes, I'm still producing stuff, working on a next project about a desirable 100 year future, a world of high tech that I want to live in and maybe other people do too. So that's my optimism at work.

Joanna: I'm looking forward to that one.

Kevin: And right now, this book will come out in May, Excellent Advice for Living. There's about 450 of them, and they're kind of little, tiny, tweetable things as you could hear, but they're short.

I wrote them for myself, primarily first, because I like to have little things that I can repeat to myself to remind me. I'll take a whole book of advice and try to reduce it down to a single sentence. Like I'm just opening up the book at random right here. It says, “Work to become, not to acquire.” I keep reminding myself that. You don't want more things, I want to become something. That's what I'm aiming to be. So yeah, I had fun writing it. This advice is really for anybody young or young at heart, and I hope you enjoy it.

Joanna: Oh, well, thanks so much, Kevin. That was great.

Always great to get thought-provoking perspectives from TCP. Kevin’s prototype comparison to writing makes sense. In 2016 I commuted to Boston to help friends spin out a NewCo. I spent a lot of time coaching brilliant young biomedical engineers from Harvard and MIT as they worked on the prototype stage of a cutting-edge technology. I was shocked when they admitted to me that they were just “McGivering” (TV gadget show) as they used trial and error to overcome major technical hurdles. I never made Kevin’s connection to writing but our first drafts do seem like those bioengineering prototypes…as we also develop unique new innovations for our readers. Loved Kevin’s ideas about how we can iteratively capture “intern value” from chat bots and image bots! BTW, still thinking about how to apply Halima’s PR concepts with my first book launch. She did a great job with the “story behind the story.”

Glad you’re still enjoying the show, Rick!

Great interview! I was nervous at first of the idea of AI with writing because I didn’t understand the level it can do and if it would take away from authors but knowing that AI isn’t perfect and we still are expected to improve upon their work is a great relief. I don’t want to become obsolete as a writer 🙂

Glad it helped 🙂 I have another few episodes coming on AI which will hopefully help you understand the possibilities.

This makes me feel much better because I am absolutely terrible at focussing on just one thing despite the apparent logic of that advice.

Me too, lol!

Another great guest ~ as an “Input” person on the Gallup StrengthsFinder thingy curiosity is extremely high on my must-have list. I find that just asking questions about others, myself, and situations–all help feed my curiosity and cause me to think in a different way.

Off to check out Kevin’s books now! Thanks again, this was very inspiring.