Podcast: Download (Duration: 53:45 — 43.7MB)

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

How can you write a book proposal that will make a publisher want to buy your book? How can you write a successful non-fiction book that both interests you and attracts a lot of readers? How can you improve your communication in person and online? Charles Duhigg gives his thoughts.

In the intro, HarperCollins CEO Brian Murray on audiobooks and AI [TechCrunch]; OpenAI's 12 days including Sora and o1; Google Notebook LM expansion; How Creatives Might Survive and Thrive in a Post-Productivity World [Monica Leonelle]. Plus, How to Write Non-Fiction, Second Edition.

Today's show is sponsored by Draft2Digital, self-publishing with support, where you can get free formatting, free distribution to multiple stores, and a host of other benefits. Just go to www.draft2digital.com to get started.

This show is also supported by my Patrons. Join my Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn

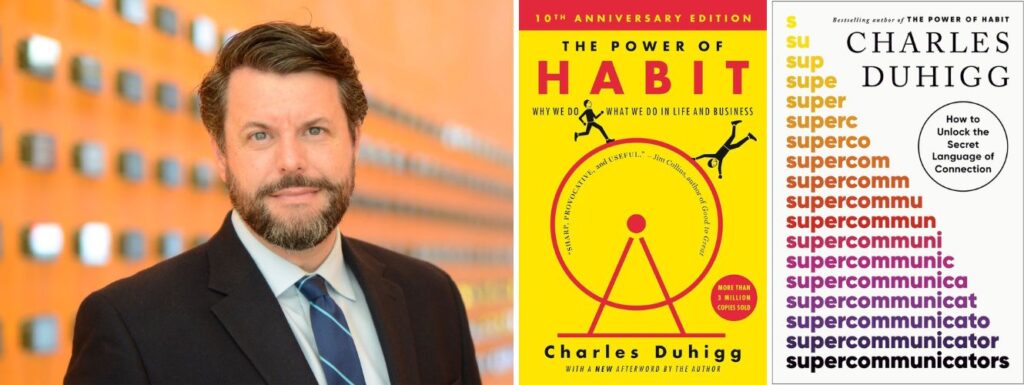

Charles Duhigg is a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, a reporter at The New Yorker Magazine, and a multi-award-winning author whose book, The Power of Habit, spent three years on the New York Times list. His latest New York Times bestselling book is Supercommunicators: How to Unlock the Secret Language of Connection.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- How the writing process differs between books and magazines

- Balancing what readers want to read and what you want to write

- Research that comes before and after a book proposal

- Tips for conducting successful research interviews

- The process of organizing research for a nonfiction book

- Improving the art of written communication

- Dealing with the fear of miscommunication and judgement

- The importance of connection in communication

You can find Charles at CharlesDuhigg.com.

Transcript of Interview with Charles Duhigg

Joanna: Charles Duhigg is a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, a reporter at The New Yorker Magazine, and a multi-award-winning author whose book, The Power of Habit, spent three years on the New York Times list.

His latest New York Times bestselling book is Supercommunicators: How to Unlock the Secret Language of Connection. Welcome to the show, Charles.

Charles: Thank you for having me. This is such a treat.

Joanna: I'm excited to talk to you. So first up—

Why did you get into writing books when journalism has clearly been such a success for you?

Charles: Well, it actually started when my wife was pregnant with our first child, and we didn't have any money, and so I thought, okay, I'll go write a book. Maybe that'll give me enough money so that maybe we can find a decent place to live.

My first book was The Power of Habit, about the science of habit formation, and it really came out of my own problems and questions. I wanted to figure out how to improve my habits, how to be able to lose weight and exercise more easily.

The process of writing a book, I found, is such a total joy and also overwhelmingly hard.

You get to get so deep into the material, you get to understand what's going on. Not only what experts are telling you and what stories you ought to tell, but also you get to think about the ideas in really profound ways.

So that just kind of became an addiction for me. I've really enjoyed writing books. Even though if you asked me in the middle of them, I would tell you it's the worst thing I've ever done in my entire life.

Joanna: Well, yes, all of us listening understand that.

It is interesting because, I mean, there's a lot of comparisons to your journalism. You interview a lot of people, and you include a lot of that.

How is the process of these longer form books different to your journalism pieces?

Charles: So it's a little akin to writing magazine pieces, because oftentimes for the magazine piece, I'll write 8,000 to 12,000 words, and each chapter of a book is about 7,500 to 9,500 words. So it's not that far off.

The difference is that when I'm writing a magazine piece, I can just write a magazine piece about whatever the topic is. I can write about AI, or I can write about politics.

With a book, you're writing the equivalent of, let's say, eight to ten magazine pieces, but there has to be something that ties them together.

There has to be an overarching argument or an overarching idea that every chapter reflects in a different way, and finding that idea can take a long time.

The two hardest parts, I think, of writing a book are, first of all, deciding what topic to write on. Oftentimes, it takes me a year or two to really figure out a topic that I think is going to be interesting and that I think readers are going to think of as interesting.

Then it oftentimes takes another year or six months to figure out what the overarching argument is. Oftentimes it's not obvious from the reporting what that connective tissue is, but it's my job to find it.

Joanna: That's really interesting that it takes you a year or two to figure out what you want to write. You mentioned there what you're interested in, but also want the what the readers want. So what is that process? Because this is something we all struggle with. I write fiction as well, and much of my audience do.

How do you find where those two things — what you want, and what the readers want — interconnect?

Charles: I think a big part of it is you just have to indulge things and then be prepared for them not to be successes.

So take Supercommunicators, my most recent book, which is about the science of communication. It originally started with me trying to figure out why some people were better listeners than others.

I thought it was a book about listening, but the thing is, that as I talked about it with my editor and as I did research, I realized listening is a little boring on its own. Most people don't wake up saying, “I really want to be a great listener.” They say, “I want to be a great listener and I want other people to listen to me.”

So it took a little while to figure out, okay, this is actually about communication. Then once we started figuring out it was about communication, it also got a little bit boring to me.

It just seemed like there was so much research and so much advice out there on, “This is how you should hold your arms,” or, “This is how you should repeat back what the person said.”

After a little while, and particularly after talking to neuroscientists about why communication works within our brains, what I realized is it's actually not a book about communication, it's a book about connection. How do we connect with other people?

The methodology for connection is often conversation.

Communication and conversation is how we connect, but the thing that is under that is how to connect with other people.

Now that question, how do I connect with anyone? That seems like a question that a lot of people would be interested in. I can see myself caring about that when it comes to parenting. I can see myself caring about that when it comes to managing people at work.

I can see me caring about that when it comes to sales or being in government or trying to evaluate political leaders.

So the process of figuring out what is both interesting to me and interesting to a broad audience is a matter of listening to my own curiosity —

Following my own curiosity, but also being challenging and skeptical.

Just because I think it's interesting, I need to prove to myself and my editor that many, many other people will think it's interesting as well.

Joanna: So you mentioned there about proving to your editor and also finding a connection with the market that might buy the book. I'm interested because, obviously, you're several books in, you're very successful, do you still do a book proposal when you have an idea?

Charles: Absolutely.

Joanna: Tell us about that because it feels like that's something we need to know about.

Charles: For nonfiction is a little bit different than for fiction.

In nonfiction, you put together a book proposal, you sell the book proposal, and they give you an advance based on the book proposal.

Then you use that advance to essentially go write the book.

I mean, in theory, I could hand my editor a two or three page book proposal and say, “Let's sell this,” but the thing is, I have to do the work at some point. You have to come up with a grand outline at some point and know a map for the directions you want to move in.

So what I do is I put together a 50- to 70-page proposal. I started this with The Power of Habit before I was a known writer, but I've used it ever since. That proposal is, first of all, written in the voice of the book. So it's actually as if you're reading little samples of chapters from the book.

So there's little anecdotes in there, there's interviews. What I'm trying to do is I'm trying to prove to myself, as much as my editor, there's enough here for a book. Like if I spend another two or three years reporting on this, I'm going to come back with something amazing.

So writing that proposal and polishing that proposal, again, 50 to 70 pages is pretty long, making that into something that is really compelling. That allows me to kind of stress test whether there is a book there.

If I can't write a great proposal, I'm not going to be able to write a great book.

The other thing is that for the publisher, it gives them a lot of confidence. So when writers come to me in nonfiction and they say, “How much time should I spend on my proposal?”

I always say, well, look, for your own sake, you should spend a lot of time on it, but equally for the publisher's sake. They are going to be comfortable paying you a larger advance if they have a fully fleshed out proposal. Since you have to do that work at some point, why not do it when it's going to make you a bigger advance?

So my advice to folks is that it oftentimes takes me 6 to 12 months to write a proposal, but by the time I write that proposal, I know what that book is going to be about. I figured out that overarching question, that overarching idea, that overarching theme. I figured out how each chapter fits into it, and from there, it's just labor.

Joanna: Yes, labor. The research then, because obviously you mentioned there that you're going to go on and spend more time on it, but you also said there's snippets from interviews in that proposal.

How many of those interviews are you doing up front, and how many come later?

Where's the research based?

Charles: So, both because oftentimes what happens is you write the proposal, and then once you start writing the chapter, you realize, like, oh, there's 20 other people I need to talk to. I would say for a proposal, I usually talk to at least 15 to 20, sometimes as many as 30 people.

Again, what I'm doing is I'm calling people up and I'm basically saying—these are experts, these are folks who have written a paper on communication that I think is interesting.

I'm calling them up and I'm saying, “I read your paper, and I thought it was really interesting. I'm not smart enough to really understand it, but I'm just wondering, what do you think is the most important takeaway from your research? When you're having beers with friends and they ask you what you do for a living, how do you explain to them why what you do is important?”

What I'm trying to do there is —

I'm trying to get these folks to think on my behalf, to explain to me what's interesting or important within this field that ought to be shared with other people.

The reason why I ask the question that way, almost like, “I'm too dumb to understand why you're smart, so tell me why you're smart,” is that what happens is that oftentimes people will do two things.

First of all, they'll explain to you the significance of their research, rather than just the research itself, which is really important because that helps you create this mental map of why this research matters.

Then secondly, they'll oftentimes tell you about anecdotes or little funny things that happen in their lab, or things that they didn't end up publishing, that end up being really great aspects of telling the story.

I interview a lot of people. I would say for the average book, if I talk to 20 or 25 people for the proposal, I'll easily talk to another 150 when I'm reporting the book.

My goal is the same every single time. My goal is to get this person to essentially say something they haven't said before. To explain to me not only what they've done, but why what they've done is important, and what was interesting about the process of doing it.

Joanna: Just on a sort of author technical question, how are you organizing that amount of research? Are you recording, like AI transcription? Are you keeping like little cards, like Ryan Holiday?

What is your process of organizing the research in order to go on and write the book?

Charles: So I'll tell you what I do for each chapter, and this is also what I do for magazine stories. I'll create a folder, I'll come up with a call list. I'll identify 30 or 40 people that I want to talk to, and I'll prioritize them, and I'll start with number one.

I'll reach out to them, and I'll do an interview with them. I'll ask if I can talk to them on the phone.

I'll oftentimes record that call, but the recording is really just a backup. What's important is, at least for me, is to take notes as I'm speaking to the person.

First of all, it's much more efficient than reading through a transcript, just to have notes that I take during the interview. Then second of all —

It's the process of taking notes that helps me see what's important about each conversation.

So I'm oftentimes, in these notes, I'm transcribing what they're telling me as they're telling it to me and typing quickly, but I'm also leaving little notes for myself. Like in all caps saying, like, “This is an idea,” or “We can connect this to that.”

Then once I've done all my interviews and I have a sense of what the chapter is about, I take all of my interviews and all my other research—because there's a lot of studies involved— and I take a bunch of index cards.

I go through all the interviews and all the studies, and I write on the index cards, usually just like one or two words, maybe half a sentence, of each idea or quote I might want to include in the chapter. Each chapter produces something like 200 or 300 index cards.

The idea here isn't necessarily that the index cards are exhaustive. The idea is that I’m creating an index of everything I've learned. I don't have to think right now about how I organize it, I just have to think about getting it onto these cards. In the corner I'll put where each thing came from, so it's easy to look up later if I want to look it up.

Then I'll take all those cards and I'll make little piles, and I'll try to arrange them as the sequence that they will appear in the chapter.

So if this idea comes first, and these two quotes are related to this idea, then this next idea should come second and this anecdote happens now, and I'll create little piles of cards.

I mentioned I have 150 – 200 index cards, sometimes 300. I would say that when I'm organizing them, they all get put in the organization. Only probably 50 or 60 of those cards are going to end up in the story or in the chapter, but the process of organizing is really, really important.

Our job as writers is not just to learn and convey information.

Our job is to organize the information in a way that's memorable and entertaining.

Once I have those cards together and I've organized my cards, what I do is I write just a long letter to my editor. It's almost kind of like rambling. I'm not thinking about choosing the poetic language. I'm not thinking about making sure that I'm getting to every idea in exactly the right order or setting everything up.

What I'm doing, though, is I'm basically trying to describe. It usually starts like, “This is the way this chapter will work.” Then I just start and say, like, “Oh, there's a story I'm going to tell from here. Then this guy told me this one idea that's kind of interesting.”

I'm using the organization that's occurred to me in organizing the cards to organize this letter. Then I send that letter to my editor, and that letter oftentimes will be 4000 words long. A chapter is, at most, 9500 words long. So I'm literally writing essentially the equivalent of half a chapter in a letter to my editor.

I'm not worrying about anything.

I'm not worrying about anything except trying to figure out what the ideas are and how the ideas connect to each other and in what order.

Then my editor will oftentimes write back and say, like, “This is interesting. This is interesting. This is the dumbest idea I've ever heard in my entire life.” You know, “This part's boring. This part, I kind of see where you're getting at, but I don't buy it yet.”

So I take all of that, and that's really, really useful to get someone else's feedback. Then what I'll do at that point is I'll take my cards, and I'll start organizing my cards, and sometimes I have to get extra cards. I have to do more research, as my editors pointed out.

Based on this experience of talking through the chapter, of getting feedback on the chapter, now I usually have a pretty good sense of how the chapter is going to work. I have these, let's say, 100 cards. So about half the cards I've discarded because I've realized, oh, that idea doesn't fit in here, that anecdote doesn't work.

So I have about half the cards left, and I and at that point, I start writing the chapter. Sometimes I'll actually go back to my cards as I'm writing the chapter, but the cards, actually at that point, are kind of embedded in my head.

I start writing, and there's oftentimes just as much thinking and work that happens once I start the writing part —

because I have to figure out, like, how do I make this story entertaining? How do I make this idea crisper? How do I make this something that's easy to remember?

At that point, I know where the chapter begins and ends, and I know where it's going to get to in the middle. If I do have a moment of crisis, I have these cards that I can turn to.

You know, what happens after this thing? I can't really remember. Oh, that's right, my card says I go to this thing next. That's how I write a chapter or write out a magazine article.

Joanna: That is fascinating. I know everyone's like, ooh, that is so juicy.

Charles: It's enormously inefficient, but it works.

Joanna: It works for you. Yes, I love that. I think that's really interesting.

Let's get into the book Supercommunicators, which I read on a beach in Corfu this summer and really enjoyed it. It's really about the importance of finding a connection and, obviously, the communication with others.

I was really thinking as I was reading it, I was like, okay, there's a lot of ideas around doing it in person, but for me and my audience, as authors, we primarily communicate online through emails, social media, maybe podcast interviews like this.

Much of our communication is written communication, so I wonder what thoughts you had on doing that?

Charles: Well —

I think good written prose is a conversation.

One of the core ideas in Supercommunicators is that a conversation is a back and forth. It's you expressing what kind of discussion you want to have, whether it's emotional or social or practical, and me responding to that and matching you, and then inviting you to match me.

When we don't have someone we're talking to face to face—and I think we do this digitally all the time, like we do it through text, and we do it through email, and we do it through DMs.

So let's imagine a situation where I'm writing something and the audience I'm writing it for is not going to get back to me right away. In those situations —

The best writing is me in conversation with that audience, where I'm standing in for the audience.

I'm anticipating their objections. I'm anticipating where they get bored. I'm anticipating their questions. I'm anticipating where they say, “Well, you know, you think you know it all, but here's this other thing.” I'm trying to anticipate all of that because I want this to feel like a conversation.

Oftentimes you start a chapter and you say, here's an idea, here's an argument I'm making. Now you might be saying to yourself, but why? Why is that true? Because there's all these other examples that prove that it's not true. Well, let me explain. That's a really good question.

So oftentimes I'm dialoguing with the audience in the text itself, and you can do that in a non-clumsy way. You know, “This raised the question in the protagonist's mind, so such and such,” because the protagonist is a proxy for the reader.

Every chapter that I write usually has someone in there who is a proxy for the reader.

So as I'm in conversation with that character, or as I'm in conversation with that person, that protagonist, they are asking the questions that I suspect the reader is asking. They are saying the things that I suspect the reader is saying.

Sometimes that protagonist is myself. Sometimes I come in as the author, and I say, “This didn't make any sense to me. I was skeptical,” because I know my audience is skeptical. So I think it's still a conversation, it's just a conversation where we're relying on our intuition about what the other side would say.

Then we're going out and we're testing it. We're asking people to read it, we're asking them to react to it, and we're making edits based on those reactions. That's what an editor does.

Joanna: I guess I'm thinking more of when we put stuff out on our email list or social media. It's interesting because we can anticipate a lot of what people are going to think or say.

From the book there's a great quote,

“Miscommunication occurs when people are having different kinds of conversations.”

At the moment, as we record this towards the end of 2024, obviously in the US and in the UK, we've had elections, and our society is quite fractured.

Miscommunication seems to happen a lot, and many authors are scared of saying the wrong thing, of getting canceled, of trying to communicate but failing.

What are your tips for dealing with this, as someone who does speak to much bigger audiences?

Charles: Well, I think this fear can be a little overblown. I mean, obviously, look, if you go up on a stage and you're talking about Gaza in Israel, and you're taking one side very strongly, you should anticipate that people will react. That people who disagree with you, will let you know they disagree with you.

In my experience, most of the times when we have conversations, first of all, we're often not talking about Gaza and Israel, right. We're talking about what it's like to be a parent or what it's like to be a writer.

Equally, if we are talking about these tough topics, I think the best conversations are ones where someone says, “You know what? I am not certain that I am right about this. I am not certain that I know enough to say this definitively, but let me tell you something that I'm feeling.”

“Let me tell you about something that I'm experiencing, and then I want to create space for you to share with me what you're experiencing and what you're feeling.”

If you go into a conversation, even a charged conversation, about politics, about religion, about race, if you go into it with this attitude of saying, “I'm not going to make grand, sweeping statements about what's right or wrong, I'm going to tell you what I've experienced and what I'm feeling, and I'm going to invite you to do the same.”

“My goal here is to understand you, is to understand how you see the world, and to speak in such a way that you can understand how I see the world.” I think in those conversations, those are not the conversations that end up getting us canceled.

Those are the conversations where everyone walks away saying, “Oh, that's a tough topic, but I feel better about it.” So I don't think it's something people have to be scared about.

If you're issuing polemics, if your goal is not to understand the other side and not to listen, but simply to force them to listen to you, then, yes, they might react negatively. If we're really good communicators, if we're really good writers, that's not our goal. Our goal is not to be a polemicist.

Even George Orwell was not a polemicist that ignored the concerns and feelings of the people he disagreed with.

Good writing, great writing, is writing that invites people who disagree with us into the conversation.

When we feel like we're in that conversation and we feel like we're being listened to, we don't get angry, we feel connected.

Joanna: Yes, and it is that going deeper. Reading those chapters in the book was really interesting.

Another quote here, “Asking deep questions is easier than most people realize, and more rewarding than we expect.” You mention things like emotional things, and this means we have to be vulnerable with other people.

How can we be more vulnerable and more emotional, particularly if we're worried about judgment in conversations?

Charles: Give me an example of being worried about judgment in conversations because I think, actually, most people are not worried about judgment in conversations..

Joanna: Well, I'm obviously British, and I was at a conference in America the week after the US election. I very much felt that I could not mention the situation because of the fear of offending a person, either way, not being too much in favor of whichever president.

So this sort of censorship of what are deeply meaningful things for people, when you're worried about people's judgment or it affecting business or whatever.

Charles: Well, what I would argue is that in that situation, certainly, if you're someone who says, “I hate Donald Trump,” and you go up to an American who has voted for Trump, and you say, “By the way, I hate Donald Trump. You guys are idiots for electing him,” that probably would not be great, but that's not a conversation.

That's not you trying to understand this person and trying to help them understand you. So I think something that would not be particularly scary or inappropriate would be to say, “Hey, you guys just had an election. I'm just wondering, you don't need to tell me who you voted for, but how are you feeling about the election?”

“Like, how are you feeling about what happened? Are you worried for the future? Are you happy about what's happened? What do you make of this?” Nobody's going to mind being asked that question.

What you're not saying is, “Here's my opinion. You have to listen to my opinion. I don't care about your opinion.”

What you're saying is, “I'm actually really curious in your opinion.”

You're an American, and I'm coming from overseas, and I want to know how, as an American, you sort of see this.”

There's this experiment that I do when I'm on a stage talking to an audience, where I ask everyone to turn to the person next to them and ask and answer one question, which is, “When is the last time you cried in front of another person?”

When I introduce this idea, people hate it. They think it's going to be terrible, super awkward. Then we have the conversation, and people love it. They say it's one of the best conversations they've had in the last week.

This has been studied extensively by a guy named Nicholas Epley at the University of Chicago, that people think this conversation, asking this question, is going to be awkward. They think they're not going to enjoy the discussion. They think they're not going to feel close to the person afterwards.

Then once they actually do it because they're forced to by someone on a stage, it's exactly the opposite. It's not awkward at all. They actually are fascinated to hear what the other person has to say. They feel close to them. They feel close to each other.

The thing that stops us, that triggers self-censorship, is an inability to forecast how well asking questions can go.

Now again, back to my polemics point, if you go in and you say, “I'm going to tell you why, as an American, you just chose the worst leader on earth,” then that's probably not going to go over well, but that's not a conversation. That's a polemic.

If you go in and you say, “Look, I want to understand your nation. I want to understand how you see your country. If you don't mind, I'd love to tell you how I see your country,” that back and forth, that's a discussion.

That's not going to result in anyone getting angry at each other. It's going to result in something that feels good and connected.

Joanna: So, really, what you're saying is it's just curiosity.

At heart, it's curiosity about another person and how they're feeling.

And that brings the connection that then can lead to other things.

Charles: It is curiosity, but it's also having the right goals when you open your mouth. Having the right goals when you go into a conversation.

The goal of a conversation is not to convince the other person that you're right and they're wrong, or that you're smart and they're dumb, or that they should like you, or they should admire you.

The goal of a conversation is to understand how someone else sees the world and to speak in such a way that they can understand how you see the world.

Understanding is the goal of a conversation.

When we're focused on that goal, rather than trying to “own the libs” or trying to prove that we're right and they're ignorant, when we're focused on understanding, mutual understanding, it almost always goes well.

Just look at both of our nation's histories. Our proudest moments are not when the entire nation agreed with each other, our proudest moments are when we disagreed with each other, but we felt connected to each other, and we felt unified enough to embrace those disagreements and find a way forward.

Joanna: So you mentioned goals there, and I'm fascinated with goals. Again, we're recording this at the end of 2024. A lot of people will be putting goals together for next year.

You've won a Pulitzer, which is frankly amazing, and many people would say you've hit all the goals that nonfiction authors, journalists, would want to reach. So I wondered—

How has your definition of success changed over the years? Do you still have goals?

Charles: Oh, of course. I mean, my definition of success hasn't really changed very much.

My goal and my definition of success is to write things that are beautiful and true and that people are desperate to finish.

Just because you've written one book that managed to hit that mark, that doesn't mean that you don't want to write more books that hit that mark. It doesn't mean that you don't find new ideas that you think are just as compelling and just as important.

So I've been extraordinarily lucky and enormously thankful for that luck because it's allowed me to afford a life where I can, instead of being a daily newspaper reporter, I can go and I can devote myself to writing things that are longer and harder and, frankly, riskier.

Some of them might not work because audiences might just say, like, I'm not interested. Though that's a means to an end.

The definition of success has always been the same: to write something that captures something true about the world that's interesting, and to write it in a way that you, as the reader, you just can't put it down.

You just can't wait to finish. You can't wait to inhale more of it.

I feel that way about books all the time, and it's just such a wonderful feeling. So that's my goal, to write things that other people feel that way about what I've written.

Joanna: Interesting. Well, then I'm going to come back to what you said at the beginning. So I asked you, why did you get into writing books? And you said, to try and make some money.

Just for people listening because, again, it's very hard to look at someone's career and say, “Oh, I should just do exactly that, and I will make some money.”

What is your advice to authors who want to make money with their books?

Charles: The number one thing I would say is you have to choose topics that have the audience in mind.

I've come up with 20 or 30 book ideas that I thought were just fascinating, and the reason I didn't write them is because I did not think enough other people would think it was fascinating.

If you want to make a living as a writer, you can't indulge just your own interests. You have to be a servant of the reader.

That doesn't mean that we're beholden to the reader.

That doesn't mean that we dumb our things down because we think the reader wants it dumbed down or that we don't investigate avenues that we think might challenge the reader, but at some level, we have to be writing for the reader, as opposed to writing for ourselves.

The bookstores are filled with these beautiful, beautiful novels and beautiful nonfiction books that are so intricate, and so well reported, and so well written, and they're on topics that I just don't care about.

I'm not that interested in the Bhutan Death March, but I am interested in, for instance, cancer. I've worried about cancer, I've lost family members to cancer.

So I'd skip over a book about the Bhutan Death March, even though it's a beautiful book, and I'd pick up The Emperor of All Maladies, a book about the history of cancer, because it's something that speaks to me. So I think authors who think about the reader are authors who end up finding readers.

Joanna: Perfect.

Where can people find you and your books online?

Charles: Absolutely. So they're sold anywhere you buy books. They're on Amazon.com, or Audible if you like audiobooks. They're in your local bookstore, and supporting and celebrating independent bookstores is always important.

If they want to find me, I'm at CharlesDuhigg.com or on all the social media stuff. I'm the only Charles Duhigg on Earth, and so I'm relatively easy to find.

Joanna: Brilliant. Well, thanks so much for your time, Charles. That was fantastic.

Charles: Thank you.

Leave a Reply