OLD POST ALERT! This is an older post and although you might find some useful tips, any technical or publishing information is likely to be out of date. Please click on Start Here on the menu bar above to find links to my most useful articles, videos and podcast. Thanks and happy writing! – Joanna Penn

Podcast: Download (Duration: 58:22 — 46.9MB)

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

If a reader can't put your book down, it's because you wrote a good story.

And if a reader makes it to the end of the book and is satisfied, they are likely to buy your next book. And that makes for happy readers … and writers! In today's show, I interview Shawn Coyne about his book, The Story Grid, which deconstructs the most effective way to tell stories based on the books we know and love.

And if a reader makes it to the end of the book and is satisfied, they are likely to buy your next book. And that makes for happy readers … and writers! In today's show, I interview Shawn Coyne about his book, The Story Grid, which deconstructs the most effective way to tell stories based on the books we know and love.

In the introduction, I mention Amazon's direct marketing tool for authors, offering pay-per-click style advertising opportunity – but it's only for those people in KDP Select. I also talk about the new Author Earnings report, and my personal writing update.

This podcast is sponsored by Kobo Writing Life, which helps authors self-publish and reach readers in global markets

Kobo’s financial support pays for the hosting and transcription, and if you enjoy the show, you can now support my time on Patreon. Thank you for your support!

You can listen above or on iTunes or Stitcher, watch the interview on YouTube here or read the notes and links below.

- Shawn's 25 years of publishing experience as an editor has enabled him to break down the best way to tell a story.

Writers need to learn how to edit themselves.

- What do writers get wrong? Writers seem to be fearful or have contempt for ‘genre,' even though this is core to story. Every story has a genre – it's just a way of classifying what we've been telling for thousands of years. Writers need to embrace genre.

- This will help you ask the right questions to work out if your book is working. Genre as Amazon category and how publishing has developed genre for the industry.

- On writing as an artist, vs editing from the structural angle. Don't edit on a first draft. The goal for your first draft is to get to the end. Shawn recommends an overview map, that gives you a highlight of what you need to hit in the story.

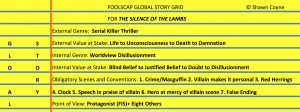

He calls this the Foolscap Method: what genre do you want to write in? Beginning hook, middle build and ending pay-off. It's for when you want to take your story to the next level, OR/ it's just a mess and you need to get it into shape. Change ‘hats' to become an editor.

- On getting better as a writer over time, with more books and stories under your belt.

On the change in story values and polarity shift in a scene

- Story values are positive or negative things in our lives e.g. life vs death – but there's also the fate worse than death = damnation; or justice – unfairness – injustice – tyranny. Damnation and tyranny here are the ‘negation of the negation,' a very powerful change for a story.

- The primary unit for a novelist or screenwriter is the scene. It has to have a value at state. It might be the overarching value of the whole story, OR/ it's a value within the scene. When you start the scene, you are at a value – then turning point, something happens – and you end up at the polarity shift of values. A scene moves from one value to another – of a different polarity.

- On writing screenplays to improve your storytelling, and some of the pros and cons of screenwriting.

Characteristics of breakout stories

- Example of LA Requiem by Robert Crais, before he was a huge name. Taking the character to the negation of the negation, and going through extreme change, which means nothing will ever be the same. This is really back to story values. Understand the core value of the genre you write in and taking it to the end of the line.

On being a creative entrepreneur

- Black Irish Books' motto is “get in the ring.” This is to encourage authors to fight the creative fight, do those things that you know you have to push yourself into. Fight the inner war of Resistance.

- On indie publishing and the new digital revolution. How Shawn has shifted from mainstream big publishers to choosing himself and starting Black Irish. Part of that decision is based on freedom of creative expression and the ability to try things out. On the entrepreneurial mindset and the type of person who suits the indie way of doing things. You can learn it, for sure, but there are people who are more suited to it. On launching and the long haul approach.

You can find Shawn Coyne at TheStoryGrid.com and Story Grid is here on Amazon. You can also find Black Irish Books and their books and audios here.

Transcription of the interview with Shawn Coyne

Joanna: Hi, everyone, I’m Joanna Penn from TheCreativePenn.com, and today I’m here with Shawn Coyne. Hi, Shawn.

Shawn: Hi, Joanna, thanks for having me.

Joanna: It’s great to have you on the show. Just a little bit of an introduction: Shawn is an editor, publisher, literary agent, and writer. He’s one half of Black Irish Books, alongside Steven Pressfield, and he has a book coming out soon, called “The Story Grid,” which we’re talking about today—it’s very exciting.

So, Shawn, just to get started, you’ve been working with story and authors and books for 25 years; why this book, and why now?

Shawn: Well, the thing is, it took me a long time to learn actually how to do this, and over the years, I discovered that there wasn’t one text on how to edit a book, so I had to kind of develop my own system. Over that time, I’ve published and been part of over 300 books; I learned a little bit from each experience, and finally I started using this system, probably around 1995 or 1996, and that’s, coincidentally, when I started working with Steven Pressfield.

One of the first books that I worked with him on was “Gates of Fire.” Steve had given me the manuscript, and I went through it, and I said, “Oh, I’m going to put my grid on it,” and he was like, “What are you talking about, a grid, what do you mean?” So, over the years, I would tell him about this system, and eventually he said, “Just show me what it is that you do internally,” because I’d always sort of not use it because I thought nobody would really understand what I was talking about.

So I showed it to him one day, and he said, “You’ve got to write this book.” One of the major things that Steve always says is that writers need to learn how to edit themselves, and I couldn’t agree more. So the reason why it’s taken this long is a) it took me a long time to develop the system, and b) I was always sort of, “Well, whatever I know everybody knows anyway.” So when Steve said, “It’s really important that other people know what you’re doing,” that’s when I decided to do it now.

It’s taken me a good 15 months to actually get it all down, and I’m just at the finish line, as you know, that’s when all hell breaks loose!

Joanna: Yes, because you didn’t do cover design or any of that. We’ll come back to the business later, but you’re certainly going further than it used to. We’re going to come back to the Grid in a minute, because it’s really interesting and obviously detailed, but in your years of experience—because, of course, you mentioned self-editing, which is a skill authors need.

What do novel writers in particular get wrong with story that you wanted to highlight in the book?

Shawn: Well, one of my big things, and it’s one of the reasons why I call my literary agency Genre Management Incorporates, is that writers are just so fearful, for some reason, or have contempt for—I don’t know if that’s too strong—genre in and of itself. When somebody says, “Oh, that’s a genre book,” people immediately start to think of cheesy pulp fiction from the 1950s, and that is absolutely not the case. Every single novel, every single story: genre is just a fancy word for classifying those myths and great stories that we’ve been telling ourselves for thousands of years.

So the big mistake that writers make is they don’t embrace genre, and to understand exactly if they work within the genre structures, it will be immensely helpful whenever they hit a really bad patch of writing, or they’re just not inspired: there’s a whole series of questions that you can ask yourself that will get you going again.

Joanna: Which you go into in the book. Behind you, there’s actually the Clover, isn’t there. People can see that on the video, which is the Genre Clover. It’s interesting.

On genre, now, in my mind, because I do a lot online, genre to me is equal to an Amazon category. What would you say to that?

Shawn: Well, I think that’s a really interesting point. Just to get a little bit into the business of book publishing, years ago, when I first started, there was no Amazon, of course, so all the major publishers had to have a farm system of genre writers, who would be managed by an editor. One of the things that I did to get in was to specialize in mystery and crime fiction. So, when I started, I would bring in a lot of fresh blood and new writers, and I would work with them, and hopefully they would build up to become Michael Connolly or James Lee Burke, or Robert Crais: these are guys that I got to work with in my early years. It was wonderful to watch them move up.

So, back when the digital revolution came about, a lot of that work sort of fell by the wayside at the major publishers, so Amazon, wisely, started embracing genre again. Then they started these imprints, and they are now the farm system, in a lot of ways, for a lot of the up and coming young writers.

Genre does have connotations of crime, horror, love story, all those things, and I think that’s a great thing to remember, but it also has connotations for inner, internal plot movements, too, like the Maturation Plot, the Redemption Plot, all of those things that we think of more of literary writers: those are part of genre, too. Amazon has sort of taken the content genre business and taken advantage of the fact that the major publishers are no longer in the building game; they’re more in the breakout bestseller game.

Joanna: Which is fascinating. We’ll come back to your opinion on publishing a bit later! But let’s go into the Grid for a bit. The book is—I don’t want to say dense in a heavy way, I mean, it’s packed full of stuff. There is no way we can go into everything in this interview. I wanted to kind of tackle some higher-level bits. Let’s just even go into the concept. Some of the stuff you’re saying, you’re breaking a structure into sections, and a lot of writers resist this deconstruction of a story: “Why can’t I just write what I love to write and let it flow and blah-blah-blah?”

So, how do we manage that creative side versus your Grid and this structure?

Shawn: Well, I would literally think of yourself in two very specific ways, and I think you’re absolutely right: the writer person needs to be free. They just do. And needs to be open to being able to flow with whatever it is is coming off their subconscious, or whatever. So, when you’re writing your first draft, don’t edit. Don’t begin your day by going over what you wrote yesterday. Don’t even look at it. And one of the things that Steve Pressfield, my business partner, and I talk about is that the goal for your first draft is get to the end. Work as quickly as you can; let that brain go anyplace it wants. Don’t worry about any questions about genre or about anything of that nature. Just more forward.

Now, with that said, before you begin writing your first draft, I think it’s important to set out a map: a very, very simple form that will give you the highlights and the points where you need to hit, as if you were driving across the United States from New York to Los Angeles, you know, you’ve got to either go to Ohio or you’re going to take a detour and go through Nashville, or whatever. So, before you do begin your first draft, I created something that I called the “Foolscap Global Story Grid,” which is inspired from Steve, and it’s just a one sheet of paper that outlines some general questions.

Now, there’s only really four major questions that you have to answer before you can start working through your first draft, and that is: What genre do you want to write in? Do you want to write a thriller, do you want to write a love story, do you want to write a coming of age novel, whatever it is? Just write that down at the top of the page: “I want to write a novel about a coming of age story.”

And then what I suggest is do three things: Your beginning hook, your middle build and your ending pay-off. Literally write down what is your beginning hook? For a coming of age story, perhaps it would be “Young girl witnesses the murder of her father,” is the opening inciting incident of a story that’s coming of age. Then you would write down your middle build: What happens to that girl from the beginning of the story until the very end. Usually, I would do the inciting incident and the ending pay-off at the same time, and then fill in the middle, because the ending pay-off has to mirror the inciting incident, right?

The great thing about stories, and this is just universal: You want to hook somebody, and that hook has to pay off.

So, the ending of the story has to be inevitable but surprising. That’s generally what a story is. You hook somebody with a really—A guy walks into a bar—and then at the end, you’ve got to make it inevitable, and surprising.

So, that is how I would say to start as a writer. And then, with that one sheet of paper, go to town. Write your first draft, let it sail; don’t edit yourself. Then, after you’ve finished your draft, literally, put on a different shirt, put on a hat, put on something. Just anthropomorphize the editor self, and say, “OK, now I’m going to look at this as an editor,” and that’s the time to take out the story grid, because the story grid’s going to show you everything that you did right and everything that needs work.

If you’ve written a great first draft and you don’t have to do anything else, congratulations. The story grid is for those moments when you need to take your story to the next level—and everybody wants to do that—or if your story is just a mess, and you really enjoyed the process of letting your freak flag fly, and writing that big, winding thing, but now you’ve got to come down to terms with the reality of not only what it is you want to say, but the marketplace.

That’s how you separate it.

When you're a writer, be a writer; when you’re an editor, be an editor.

Joanna: So many great things there. I think it’s so interesting, because I’ve got a novel here that I’ve just printed out, and I’m going into that editor mode, and it’s so funny, because often you think you’ve nailed something—well, sometimes you do—you’re like, “Yeah, I’ve finished my draft!”, and then you go back into it and you’re, “It’s just a nightmare.” I just wanted to ask you on that, considering how many people you’ve worked with, and of course Steve, who’s one of my creative idols: does it get easier.

Have you seen writers get to a point where they have internalized that grid, so that the first draft becomes easier?

For example, referring to Lee Child, who famously only writes one draft, I think it’s because he spent 30 years in television, so he kind of internalized that. When does that happen, so I can look forward to it?

Shawn: Well, it will happen, the longer you do it, and you will start to do it intuitively. Steve still does the Foolscap before a project, but he doesn’t do it nearly in the detail that I prescribe in “The Story Grid.” “The Story Grid” is really like an owner’s manual for the editorial process. There’s a ton of stuff in there that you may never need and probably shouldn’t even concern yourself with.

To answer your question, it does become internalized after a while, and I think you’re absolutely right about Lee Child; I mean, there’s a guy that had to bang out beginning hook, middle build, ending pay-off time and time again, so that he doesn’t think about it anymore. It’s a natural thing. Now the thing about Steve, there’s a very short story about Steve: Steve has written so many great novels, and even he, years ago, had reached a sticking point. He had a novel called “The Profession,” which he’d been working on for a couple of years, and he just couldn’t crack it. He had written draft after draft, and he gave it to me, and I read it, and over a few weeks, we worked through it, and we discovered he missed a major shifting point in the middle build. Once he solved that, then he could finish off the book.

So, even with the pros, there’s going to come a time, and it’s usually that book that they’re stretching; they’re trying to take it to the next level, where something internally shuts down and they forget their core principles. So that’s why the story grid and editing is such a useful tool, is that it will walk you off of the bridge; it will get you back to reality. Your story has a problem: there’s a solution. All you have to do is find those problems and eventually you’ll fix them. It just makes that much sense. The trouble is finding the problems, and that’s what editors used to do in book publishing, and they had a lot of time to do it—they don't have that time anymore.

So you have to learn how to edit yourself.

Joanna: It’s so interesting you say that, and I’ve found as I’ve mapped out, and I use Scrivener, and I’ve been using the notes on the right-hand side to kind of ask the questions, do an overview and then see the polarity shift or the value change, and I wondered if you could talk about that, because I only learned about that recently at a Robert McKee seminar, where he talked about story values and the positive and negative charge. I was so interested that you talk about this as well. It was a real penny-dropping moment for me.

What are story values?

Shawn: Sure. Story values are very simple. They’re positive or negative things in our lives. So, for instance, life-death, and there’s a polarity shift from life to death. There’s life, there’s unconsciousness, there’s death, and then there’s the fate worse than death, which is damnation. So, there’s sort of this spectrum of the life-death value. For instance, justice has the same sort of thing. It has justice and fairness, injustice and tyranny.

These are the values, hope-despair, these are the things that we all think about in our lives, that we are constantly emotionally affected by in our everyday life. We just don’t think of them so clearly and rationally, but when you are a writer, you need to do that. The reason why you need to do that is that the primary unit of story for a novelist or screen writer is the scene. Now, the scene needs to have a value at stake. That doesn’t mean it has to be the exact value of the global value at stake for a specific genre.

For example, the global value at stake for a crime novel is justice: are they going to catch the criminal or aren’t they? So, you can have a crime novel with a scene within that novel has nothing to do with justice, but has everything to do with, say, hope-despair. The beginning of your scene, you want to be at one side of the spectrum. Hope: your detective is hopeful that this lead is going to encourage him and lead to another lead, and eventually lead to the solving of the case. So that’s how you would begin that scene. And then at your turning point, in the middle, something has to happen where his expectations are not met, and he reaches a level of despair.

So, that’s a scene that makes a lot of sense, because it’s moving from a positive at the very beginning of that scene to a negative charge at the end. The reader is, “Oh, wow, this is great, this coup is going to pay off … oh, no, it doesn’t, oh that’s terrible: I wonder what’s going to happen next.” So that’s the polarity of shift that can keep the reader engaged.

First of all, if you never shift a value in a scene, it’s not a scene.

It’s exposition, it’s fancy writing, it’s a lot of things, but it’s not a scene. A scene moves a value from one to another, from a positive to a negative, a negative to a positive: it can go negative – double negative; it can go positive – double positive—you win the lottery, and you’re getting married!

Joanna: That’s usually the start and then it gets worse!

Shawn: Anybody can take that any way they want! But it has to be moved. Robert McKee is a client of mine, so there’s a reason why: I’ve been studying Bob’s stuff for years, because I’ve known him for 15 years. My goal is to download everything that Bob knows about storytelling into books, and we’re working on a book right now together on dialogue, which is fantastic, in fact.

Joanna: Wonderful—I’m so looking forward to that! I didn’t know that you were working so closely with him. An amazing guy. What a performer!

Shawn: Oh, fantastic. Yes, that movie, Adaptation, that’s fantastic. He nails Bob perfectly.

Joanna: You mentioned screen writing there, and of course Bob teaches about screen writing. I’m fascinated by this, and I want to write a screenplay, maybe because it has different aspects to it.

Should novel writers in particular write screenplay—or at least try—because it helps you with this type of thing?

Shawn: Oh, absolutely, I think so. Beyond the fact that you can’t really bullshit in a screenplay, because you’ve got to turn a scene or it just sits there on the page and nobody understands what’s going on, the wonderful thing about writing a screenplay is you have to think visually, because exposition—meaning how somebody felt or how somebody looked—you can’t have that in a screenplay. So it makes you boil down whatever it is you’re trying to say into visual terms.

Now, some of the best writing captures visual life. For instance, if somebody says, “How was your day today?” you say, “Oh, it was good”: that doesn’t really mean anything, but if you say, “Oh, it was wonderful: I met this really, really sweet person and we went to coffee at that coffee shop that has the ferns”—if you can describe things visually, then that visual presence reaches the readers’ minds. So to practice writing visually and to think visually, writing a screenplay is going to be extraordinarily helpful.

Joanna: Just on the adapting novels, obviously Steven Pressfield started with screenplays and moved into novels. If one has novels, like I do, for example, would you recommend adapting—I mean, I’m looking at one of my novellas, because obviously the length, as well, is much shorter.

Should one adapt, give it a go, or is it best to try to write something from scratch?

Shawn: Well, it depends. I think the tricky part about adapting your own work is that—and this happens in Hollywood a lot: a lot of my clients will write a terrific thriller, and then a studio or something will want to option, and then my client will say, “Can I get a shot at writing the screenplay?” and Hollywood hates that.

Joanna: They want the writer gone, right!

Shawn: Exactly. Beyond the fact that they want the writer gone, it usually ends up where the writer has a really strong vision of what they see, and they can bring it to bear in the novel, but the screenplay becomes a little muddled, and it doesn’t seem to have as strong a point of view or strength as it does in the novel. But what I would recommend is to find a contemporary’s novel or short story and think about adapting that, or creating an original screenplay. Adapting your own can work, it really can. I mean, “Gone Girl” was adapted by the writer: terrific. Great book, great screenplay, she’s doing more and more screenplays now. But she wrote two novels before she did that, and she was a journalist before that, too, so, again, it’s like the Lee Child thing, where these people have been doing the hooks, builds and pay-offs for so long that eventually it becomes almost automatic and within themselves.

I don’t think I’m answering your question very well, but it can get tricky to adapt your own work, because you fall in love with certain things and you can’t let them go.

Joanna: No, and it’s funny, because I’ve been to a few screen writing festivals and I’ve been learning about this, and the thing that stops me, I think, and Steve Pressfield talks about this, is that you can write screenplays and if nobody buys them—even if they do get bought, they might not get made—you might never make any money out of screen writing, whereas now, because of self-publishing, if you write a novel that’s even half-way decent, and you get an editor and you get a cover, you can still make money out of a novel. A screenplay, most of them just seem to sit in drawers!

Shawn: They do; they really do. I mean, I also represent David Mamet-

Joanna: He self-publishes now, right?

Shawn: He does occasionally, but he was just recently published by Penguin, too. But he’s had 25 things produced, and he’s probably written 50 screenplays, and the other ones, they’ve been bought, and they’re sitting somewhere in some box. So that can get a little depressing, too!

Joanna: I hate that thought! So, let’s come back to the breakout idea. You’ve mentioned that you’ve worked with some of these breakout mystery writers, and one of the other things in the book is about emotion.

Does having a breakout book mean that you have tapped into some emotion? Or what are some of the things that you see amongst the books that have broken out, in terms of elements of story?

Shawn: That’s a really great question, and that’s the million dollar question in book publishing. It was one of the things that they entrusted me to do at Doubleday when I was there years ago—to varying degrees of success. But I will say this, and I’ll use an example of a breakout book that I worked on with Robert Crais, which was “LA Requiem,” this was back in 1998 or so. Bob is a number one New York Times bestseller now. But at the time, he had written this wonderful book featuring his recurring character, Elvis Cole, and it also had Joe Pike, his second sort of major character, but Joe was sort of a little bit lost in the background. And he was transitioning at the time, Bob was, from making his lead character less sort of really smart and kind of cynical to a deeper character that people would follow from book to book.

So, the thing that we needed to do was take the value in the thriller, in the crime story, to the negation of the negation.

I’ve written about this recently on Steve Pressfield’s blog, but what the negation of the negation means is to take the story to the very, very limits of human experience; to the end of the line, to the point when there’s no turning back, the lead character’s going to be forever changed, his life seems to be in a shambles, and he has to pick up the pieces and deal with it. As I write a lot, stories are about change. And none of us likes change: we all like our routines, our habits: when things are working well for us and we can just do this, that and the other, we feel OK.

But when we’re challenged, we have to move, if something terrible happens in our life and we’ve got to completely change who we are, we don’t like to do that. That’s why people love stories, is that when you can read a book, and you can attach to a protagonist who is going through the same sort of similar emotional turmoil that you do, then you feel, “Oh well, maybe I can get through this move, if Elvis Cole can get over the death of the woman that he would die for 25 times over.”

When we did work on that book, we discovered that we needed to take Cole to the end of the line, which was a level of damnation. Would an action that he makes damn himself or—and that brings in the villain, of course, too. It’s interesting that you brought up story values earlier, because that is really the answer to the riddle, is to understand the core value of the genre that you’re writing in, and taking it to the end of the line.

I could go on for hours about the negation of negation, and I know that Bob covers it very well in the story, but it’s really important, if you want to write that break-out book, that people are going- I mean, one of my all-time favorites is “Silence of the Lambs,” and that is what I analyze in “The Story Grid.” What’s so remarkable about that book is that Thomas Harris takes the book to the end of the line by the mid-point of that novel, and so you are so emotionally attached to those characters that, reading the last half of that book, you stay up all night, and can’t help yourself, and that’s the goal.

Joanna: The negation of the negation confused me quite a lot.

When we say life-death-damnation, that is a kind of obvious one, but you can’t use obvious ones every time. So in your book, “The Story Grid,” do you actually give a nice list of positive, negative and then the negation of the negation?

Shawn: Yes! The most important thing is that, when we were talking earlier about the story values, in scenes, you don’t have to go to the negation of the negation. In fact, if you do, it’s going to seem melodramatic; it’s going to seem like a soap opera. But in the core value, meaning the overall value of the genre that you’re working on, you need to, for a breakout book. You don’t always have to: in crime stories, there are wonderful mysteries—Agatha Christie never went to the negation of the negation. Damnation was never in play, because we were enthralled by her inspectors figuring out, Miss Marple or Poirot, we were dazzled by their erudition and how were they going to figure this out? They’re the master detectives. The same thing with Columbo. Those stories never go to the negation of negation.

But if you want to write a breakout thriller that Hollywood’s going to buy, you’ve got “The Silence of the Lambs,” which is the pre-eminent serial killer thriller. I mean, he wrote “Red Dragon”: he basically invented the serial killer thriller, and then he made it even better with “The Silence of the Lambs.” If you want to write that kind of story, the core value of the thriller is life-death, as it is in action or in horror. And horror and crime and action make the thriller. Anyway, I could go on.

But the thing to remember is that the negation of negation in the core value is what will give you the opportunity to write the breakout book.

So, if you’re writing a love story, a love story, like, say, Judith Guest’s book, “Ordinary People,” the negation of the negation in that love story is hate masquerading as love. If you remember that story, the mother hated her son for surviving the terrible accident and the other son that she adored died, but she would never admit that. She never admitted it to herself. So, by the end of that story, she is so unwilling to admit that she does not like one of her sons and adored the other that she’s willing to leave the family. And that rips our heart out, because we can understand that self-deception. So there’s a very confined story, set among three people, that goes through the negation of negation, that is a breakout book and rips your heart out. So you don’t have to write “The Silence of the Lambs,” if you can write “Ordinary People” or anything like that, or “Sophie’s Choice,” I mean, come on—you can go into the literary world the same way as you do the crime fiction world, and thrillers and everything like that.

Joanna: I think for people listening, this is much more complicated than one thinks it is initially. There is so much to this, and it’s fascinating, so I urge people to check out “The Story Grid,” the book, and also your website, thestorygrid.com, which has got a lot more detail about this. But before we go, I wanted to ask you just a couple of questions about the entrepreneurship side.

You and Steve Pressfield have a company called Black Irish Books, and your motto is “Get in the ring,” which I really like. Tell us, why is that the motto and what does that mean for writers?

Shawn: The motto is basically to encourage people to fight what Steve and I call the inner war. And the inner war is that thing that he talks about and writes about in “The War of Art,” which I edited and published 12 years ago, when I had an independent publishing company. So, we started Black Irish Books when “The War of Art” came free from the major publisher who was reprinting it, and we said to ourselves, “You know, let’s start with this little company,” and Steve came up with Black Irish Books, I won’t take credit for that. It’s because I’m Black Irish, and I get very passionate, and he’s been in meetings with me where I’m way too passionate! So he thought it would be very funny to call it that.

But “Get in the ring” means if you have something that you know you’re supposed to do—we all do, it might be gardening—do it. You’ve got to push yourself into places that will make you uncomfortable. So getting in the ring isn’t about beating up anybody else; it’s not about fighting with people;

it’s about fighting the inner war; fighting within yourself to beat down the voice inside your head that says, “You can’t do it, you’re a loser, forget it, nobody’s going to care.”

I mean, these are all the things that I faced when I was writing “The Story Grid”; everything that you face when you write.

Being an entrepreneur is exactly the same thing. People are going to tell you, “Oh, you’re crazy, you’re never going to make any money doing that. That’s silly, that’s a waste. What are you doing? Podcasts? Who cares?” You can hear that until you’re blue in the face, but the reality is that it’s not the gifts of being a businessperson or how many people buy your book: it’s when somebody says to you, “You know, I listened to that podcast that you did and it made me think about the things that I was doing in my own life”—that’s the stuff that we do it for.

And so, that is what you need to remember: that’s what fighting the inner war is about. It’s not about becoming a billionaire or a millionaire or whatever; it’s just trusting yourself enough to do what you know you should do.

Joanna: And how does that then relate to publishing? You’ve worked in big publishing, you’ve had your own press, you have the company with Steve—you wouldn’t call it self-publishing because you have a company and everything-

Shawn: We are self-publishing, this is it!

Joanna: You are indie.

Shawn: This is that whole black space: this is it.

Joanna: You’ve really shifted in your career.

What do you think right now in the publishing world, what is your opinion of the kind of indie space and where are things going?

Shawn: Well, I think there’s always going to be major publishers, and there should be. I mean, major publishers are terrific in certain things and not so good in other things. I left major publishing because I’m the kind of person who has a wild idea and I want to run with it. I just want to try it: let me try this marketing thing. And the thing with a major corporation is every once in a while, they go, “OK, Coyne, go ahead and try that,” but most of the time, they’re going to say no, and they have to say no, because they’ve got to manage hundreds of employees, warehousing and sales reports. So it got to a point in my life when I was there to say, “You know, this really isn’t for me. I should be on the outside, I shouldn’t be on the inside.” And there are tons of committed editors and marketing people, some of my best friends are still in major publishing, and that’s cool. There will always be a place for them, because they’ve got the ability to jam a book into the marketplace, and if it’s great, it can become a huge bestseller.

Look at “The Goldfinch.” I mean, that’s a great book and if that was independently published, it would have a difficult time finding a market. It really would. So there’s always going to be a place.

Now, independent publishing I think is really, really a wonderful opportunity for people who are just not going to get any love from the Big Five, and that’s pretty much everybody! You know, there’s probably 8% of people who write a novel are going to find an agent, and those agents are going to be able to place probably 70% of their stuff, because they are very selective. They have to be. And even of those, even say getting a $100,000 advance for your first novel sounds great, but it took you seven years to write it, and it’s going to take another two years to publish it, and if the book doesn’t perform in its first twelve months, the second novel isn’t going to excite anybody at the Big Five publishers.

But if you’re independent, you can publish your first novel in September and publish your second novel in October. Who cares? In fact, that’s a pretty good idea, because anybody who likes your first will want to have your second immediately.

So, there’s so many different marketing and fun opportunities, and you take advantage of all of them, Joanna, and it’s great to watch and to follow you, because you’re constantly doing and trying different things, and you’re having fun, and you’re doing non-fiction, you’re still doing your fiction. You think about your world in terms of projects rather than affirmations from third-party validation sources, and when I say that, I mean a lot of people need to be published by Random House: it just makes them feel like, “OK, my world’s OK, I’ve got Random House on the spine, that’s fine.” Other people don’t. I don’t need that, and Steven doesn’t need that any longer. But it’s OK to be there, too.

I think independent publishing is great, because you can build your own platform; you can talk to your peeps; they can buy your stuff directly; which means you don’t have to sell as many copies to make a living; which means that you can do your next project; and do another one; and you’re not sitting waiting around for someone else to pick you and say, “Oh, you’re worthy.”

Instead, you’re building your own tribe of people who think you’re terrific. And the more people who do that, the more people will read, the better it will become.

Eventually, I can see independent publishing being a global marketplace more than just the specifics. So translation rights, I mean, the thing about selling translation rights today, and I’m sure you know this, is that you often deal with the foreign publisher, they translate the book, they give you $500, and you never hear from them again; you never get any sales figures, you never build an audience in that country.

Now, we have the technology: it’s crazy not to be able to have your own website in the Czech Republic, being translated, and that’s only a matter of time for that to happen. So you can build multiple audiences around the world and increase the scale of your operations, independently. And you can do your own marketing, and nobody’s there to tell you know.

That’s the great thing about being independent, is nobody’s going to say no. If you have a crazy idea, you can do it: try it.

It might not work, as Seth Godin always says: this might not work—so what, try something else. It’s fun. Make it fun.

Joanna: It’s so good talking to you and Steve and people in the tribe, the Seth Godin tribe. We’re all so positive and happy! We love it! Which is awesome, because this is fun: I’m enjoying it, you’re clearly enjoying it. The people I worry about are the people who are not enjoying it.

Shawn: Right: they should be gardening.

Joanna: Maybe they should! But this is so interesting, because I used to think, probably up until about a year ago, that anyone could be an indie author, I really did. And now, I’m not so sure, because everything you’ve said is true, and you do have to have this kind of attitude and this entrepreneurial spirit of giving it a go, and if it fails, “Hey, whatever,” do something else resilience to do this.

So, do you think anyone can do it, or is there a personality type?

Shawn: I’m with you. I used to think that. I used to think that if I made the right arguments to people—speaking as a literary agent and entrepreneur myself—I sometimes have crazy visions for people, and say things like, “Well, you should do this and I’ll help you,” and it’s not for everybody, it really isn’t for everybody, and that’s alright. It’s OK. Everybody doesn’t need to be testing the waters all the time.

The one thing I would say is that you don’t have to do everything. You know, you’re a madwoman: you do everything. I mean, it’s great. But I can barely get the website posts up sometimes. Instead of not doing it, it comes to a point in your life where not doing it is more painful than doing it. That’s really where it is. You said at the very beginning of this podcast, “Why now?” Well, I got to the point where not doing the book became more painful than doing it. And so that’s why I’m downloading everything I’ve learned so that maybe the 26-year-old Shawn Coyne who’s out there now can have a resource that it took me 25 years to figure out. And that would have been immeasurably helpful to me 25 years ago.

So, it comes down to that. But it’s not for everybody, no, and could I get some major publisher to publish my book? Maybe, maybe not, but it doesn’t actually matter, because it’s important to me, and it’s what I’ve got. It’s not for everybody: if you like it, great; if you get nothing out of it, throw it away!

Joanna: I can’t imagine anyone not getting anything out of it. I’m in the queue, certainly. And actually, just on the launch, you and Steve also do audio and video, and at Black Irish, you have launches that are not necessarily based on Amazon, so I’ve bought audio books directly from your website, which I love, I think it’s amazing that you do that. So you’re really going that entrepreneurial route and cutting out the middle-man, and all the things that we talk about.

So, tell us where we can find “The Story Grid,” when it will be launched, and will there be some multimedia extras that we can look forward to?

Shawn: Absolutely, and that’s one of the things that’s taking a little extra time, because we have a wonderful artistic director who’s putting together a lot of the grids and the maps. Because I’m a visual person as well as a word person, so that’s the thing that I love about “The Story Grid,” is that you can see the novel, as opposed to having to go page by page.

In fact, I’m going to LA next week to meet with Steve and we’re going to film a whole bunch of stuff to talk about; we’re going to launch early March, we’re thinking the Ides of March would be a good time to launch this thing. And we’re going to include all kinds of goodies that we haven’t quite figures out yet, for the tribe.

What the tribe means is anyone who subscribes to StevenPressfield.com or thestorygrid.com is going to get a leg up. We’re going to get a deep discount on the first batch of books, because you’ve put up for so long waiting for it! And you’ll get a whole bunch of goodies, too. So, the videos we’re going to shoot, and we’ll do a YouTube thing.

That’s the other thing that people always forget, and the major publishers always forget—you can promote any time. There’s no such thing as a pub date, a launch date. There really isn't. There’s no national media anymore. So the Big Five publishers are all, “Ah, our pub date, it’s going to launch and we’ll have a two-week blitz in the media,” and then that’s it. That’s literally all they do. But Steve and I look at it like, “Hey, we’re in this for the long haul,” we’ve got stuff planned for books that we published two years ago that’s going to come out eventually. In fact, we’re overwhelmed with ideas and content. So, the short answer is yes, we’re going to have lots of video stuff, March 15 is the date it’s going to be on sale for probably Amazon people, and the tribe will get it a little bit earlier, at a cheaper price.

Joanna: I’m exciting. I’m in the tribe, and I hope everyone listening will now become one! It’s exciting times! OK, just tell everyone the website again, just so everyone knows.

Shawn: It’s www.storygrid.com

Joanna: Fantastic. Thanks so much for your time, Shawn!

Shawn: Thank you, it was wonderful. Great to talk to you.

This was an excellent interview. I loved this and I’m definitely going to grab this book and see what I learn.

I agree, this is an excellent interview, and one I will listen to again. “The negation of the negation” did my head in! (And I’ve read McKee’s Story twice, LOL!)

I actually do graph rising and falling moments in my books’ main threads, which helps a lot in the post-first-draft time for narrowing in on major structural elements, but it looks like Shawn takes this to a much higher level.

I signed up at Storygrid to be a tribe member, and this book will be a must have.

Thanks to both of you for giving so freely.

PS. Shawn’s is one of my favourite types of American accents. Not that this has to do with anything much, but he sounds like some famous actor, which makes his message seem even more authoritative!

I think I need this to keep myself structured when I write (o:

I like what was said about starting with a story question and that the ending answers this question.

Great interview! Very helpful. I have a copy of Robert Mckee’s book, but haven’t really gotten to reading it just yet. This episode convinced me that I have to read it real soon.

I’ve always loved genre books. At the same time, though, I can’t help but feel that writers that focus too much on the tropes and traditions of a specific genre are missing out. It’s start your stories out within a specific genre, but it’s also great to mix it up a little. Consider E.T. for one. I’m not sure if you can really classify it as science fiction. It has sci-fi elements, sure, but compared to other sci-fi works, it creates a completely different mood and atmosphere.

On the other hand, I totally agree with the idea that prose writers should write in scenes. I recently re-read Dwight Swain’s “Techniques of the Selling Writer” and he pretty much nails how to write your prose in a more picturesque style. Plus he talks about scenes and sequels, and what elements should go into each one. And your book, Shawn, sounds like it could greatly supplement what I’ve learned there and take it to a whole new level.

Will definitely check out The Story Grid, and start reading Robert Mckee. Thanks!

You’ll enjoy McKee – and that book is dense – so it might take a while. I also like Dwight Swain’s “Techniques of the Selling Writer” – and found it useful – it’s on my To Re-Read list 🙂

I have to wait for this book to come out? No fair. Terrific interview and a lot of useful points addressed. I’ve been reading Shawn Coyne’s blog and now know I’m not nuts (in some ways). A great deal of what we’re now learning as writers does come from the actor’s craft. My husband has been an acting coach for over 30 years, and as I’ve come back to writing and discuss certain elements with him, I mention one word like “beat” and he’s off on a 30-minute lecture. Now when the lecture begins I can kick back and say, “Well, you know Coyne says…” Plus my writing will have a map. Cool beans.

Fabulous interview. At least it was when I watched it the second time after coming out of the fog of worship creating by hearing Coyne knows James Lee Burke. Edited him. I’ve known many writers who have given up after reading Burke, thinking it just doesn’t get better than that so why try. Thanks for bringing us this fantastic person, Joanna. And thank you, Shawn, for the great teaser, the points to ponder, and that juicy blog of yours.

Thanks Cyd – I was super pleased to get Shawn on the show! We are all waiting eagerly for the book!

Great interview! Shawn, what’s the ETA on your Storygrid book? Can we pre-order? Cheers!

You can sign up at http://storygrid.com/ and you’ll get emailed when it’s all ready to order 🙂 I’m excited too!

Joanna, You always have great informative guests, but I found this episode particularly useful for getting my story structure back on track. Thank you and thanks to Shawn. I’ll definitely check the book out.

I’m a bit behind and just listened to this one. It’s a keeper for sure! Fantastic info from Shawn. Thanks so much to both of you.

Now I’m off to read all the posts on Shawn’s site and sign up to be notified when the book is out. Can’t wait!

And as someone else said, he had me at James Lee Burke. 😉

I think the story grid is a wonderful idea. However…. how do you use this grid is you are writing a multi character or plot story. i have 2 main characters and about 11 to 15 supporting characters. How do you apply the grid to that many layers??