Podcast: Download ()

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

How can writing help you through difficult times, whether that's a change you didn't anticipate or an experience of grief? How can you differentiate between writing for yourself vs. writing for publication? Karen Wyatt gives her tips.

In the intro, Amazon opens up AI narration with Audible Virtual Voice on the KDP Dashboard [KDP Help]; Voice Technologies, Streaming And Subscription Audio In A Time Of Artificial Intelligence; Spotify announces short fiction publishing for indie authors [Spotify]; Audio for Authors: Audiobooks, Podcasting, and Voice Technologies — Joanna Penn; Writing for Audio First with Jules Horne; Writing for Audiobooks: Audio-first for Flow and Impact – Jules Horne. BookVault.app is now printing in Canada, as well as Australia, UK, and US.

Plus, Measure your life by what you create: 50 by 50; and Reykjavik Art, Northern Lights, and The West Fjords: Iceland, Land of Fire and Ice; Books and Travel Podcast returns this week; Writing the Shadow on the Biz Book Broadcast with Liz Scully; ElevenLabs speech to text for dictation.

Today's show is sponsored by Draft2Digital, self-publishing with support, where you can get free formatting, free distribution to multiple stores, and a host of other benefits. Just go to www.draft2digital.com to get started.

This show is also supported by my Patrons. Join my Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn

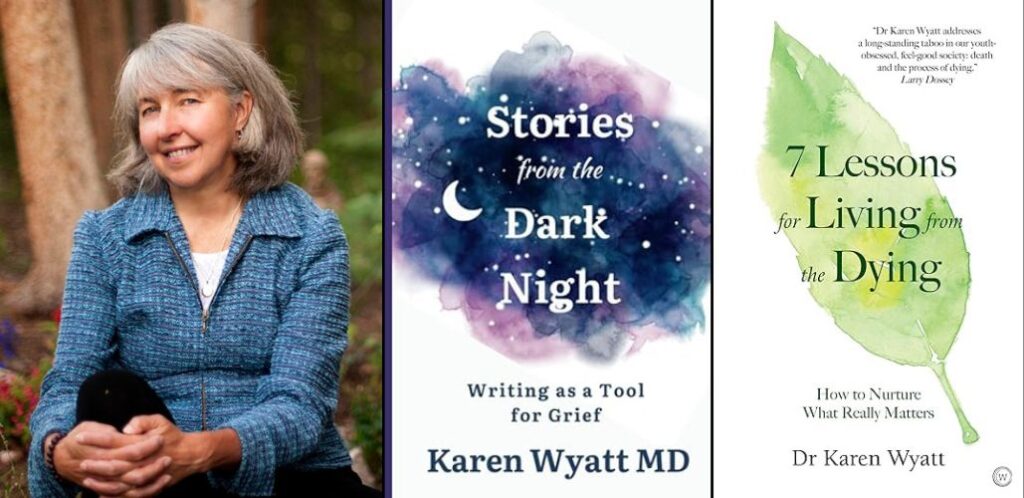

Dr. Karen Wyatt is a retired hospice physician and bestselling author of books about death, loss, and grief. She's also the host of the End-of-Life University Podcast and an inspirational speaker.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Different types of grief that we deal with throughout life

- Why write about grief and end of life?

- Using writing to deal with the complex emotions around grief

- The role of control in grief

- Transforming personal writing into publication

- How spirituality plays a role in the grieving process

- How to approach writing about family members

You can find Karen at EOLuniversity.com.

Transcript of Interview with Karen Wyatt

Joanna: Dr. Karen Wyatt is a retired hospice physician and bestselling author of books about death, loss, and grief. She's also the host of the End-of-Life University Podcast and an inspirational speaker.

Today we're talking about her book, Stories from the Dark Night: Writing as a Tool for Grief. So welcome back to the show, Karen.

Karen: Thank you, Joanna. I'm so excited to be talking to you once again.

Joanna: Yes. Now, it's been a while, so first up—

Tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing and publishing.

Karen: Well, like so many of your guests that you interview here, I've always been interested in stories. I started writing stories when I was seven years old. I wrote a three act play when I was 10, which my school ended up producing. So I guess I could say I'm a published playwright, my one and only play.

I've always loved writing down my thoughts and ideas and telling stories and writing them down. I kind of got waylaid in terms of writing by becoming a doctor. So I had a number of years there of intense schooling, and then I was a doctor and a wife and mother at the same time.

I had very, very little time for writing. It was precious time if I ever could just sit down and jot down a little story that was in my head.

Still, the creative juices kept flowing, as I know you've talked about. Like, just ideas, ideas, ideas every day for stories or things I wanted to write, but I always had to put that aside. I was just too busy.

So I finally retired from medicine early, and I was a hospice physician for a number of years. I retired early so that I could write because I'd been gathering all these stories while I worked in hospice. Amazing, beautiful stories from patients I worked with. I just knew it's time for me now to shift into writing mode.

I retired early 15 years ago, and I started writing then. I hadn't really thought about what it takes to publish a book, I didn't know that. I finally started delving into that, and through you and your podcast, I learned about independent publishing.

I've been able to publish my books myself most of the time. Though, I worked once with a hybrid publisher and then most recently with Watkins Publishing from the UK.

It's been a really fun journey for me of finally having a chance later in life to get into the writing that I started when I was seven years old.

Joanna: That's wonderful.

Just on being drawn to the darker side, I mean, obviously as a doctor, you could have gone into many different areas and ended up being a hospice physician, and—

You're writing about end of life. Has that always been an interest?

I mean, I guess I'm saying this from the perspective of someone, as you know, I have always thought about death. Like from a very young age, I remember thinking about death and dying. So it's always been on my mind. I wondered if that was true for you.

Karen: I did have some interest in death and dying. A classmate of mine died when we were 16 years old, and that kind of really woke me up to the idea that, oh, my goodness, everyone dies, and you could die at any age.

I started really contemplating my own mortality at 16. Like, you know what? Nothing's guaranteed. I could die at any time.

So I will say death has been on my thoughts since a young age.

Then early in my medical career, my father died by suicide, and I was really plunged into this whole world—and I call it my dark night of the soul, in a way—of grief after his death.

This is what led me into working for hospice because I realized, even though I had thought about death, I didn't really know anything about it. I didn't know anything about grief, even though I was a doctor. I hadn't had any training in that area.

So I started volunteering for hospice to help me understand what I was going through. What am I going through here as I'm grieving my father's death?

Ultimately, I shifted my whole career to hospice because I found it was just a rich, very spiritual, sacred place to be.

A sacred way to be a doctor with working with patients and families, and it was very powerful for me. So it was really grief itself that shifted my path as a doctor, initially.

Then, again, as I said, I started gathering so many stories and learning so many things about this process of loss and how we navigate it and cope with it in life. I really felt inspired to start writing and talking and teaching about it because at that time, it seemed like a very taboo subject. I think it still is, in many ways.

Joanna: It's so weird. You said there that as doctors, you didn't really get into the death side of things. It just seems so crazy to me because it happens to 100% of people, and it's like a physical process—obviously, much more than that.

Why aren't doctors trained on death?

Karen: It's so bizarre. I still can't wrap my head around why that is.

It's partly because modern medicine focuses so much on curing illness and saving lives that death has become the enemy. So we don't want to think about that or talk about that because we don't want it to happen for our patients.

It's ridiculous because it does happen. I think back to when a patient was approaching death in the hospital when we were in training, suddenly that patient was taken off our service.

We didn't follow them anymore because, well, they weren't a good teaching tool now because they're going to die. We'll move on to the patients that we can cure because that's what we're here to learn about.

It really doesn't make any sense, but it's part of why we have a problem with how we take care of people at the end of life. I think that's why I just felt inspired. I want to help do this differently, and that's why hospice was so appealing to me.

Joanna: And why books and writing and talking about these things are so important. As you say, there's a lot of taboo, and perhaps even more taboo around the way your father died.

Before we get into that, I just wanted us to talk about the word grief, because it feels like there are many forms of grief. It is not just if we are dying, or if our partner is dying, or our family is dying, or if someone is dying.

What are some of the other ways that grief might come up for people?

What might help them if they're feeling certain ways?

Karen: I think it is important for us to recognize that —

We feel grief whenever major changes take place in our life.

I had a mom tell me she grieved when her child no longer used baby language. Like started talking and saying words normally, and they lost all the cute little expressions that their toddler used to say.

When that was over with, she felt grief because it was a big change. Something shifted, and she lost something. So we can feel grief even in times of happiness, when good things are happening.

If you think about it, life is one series of loss and change after another. So it makes sense, in a way, grief is kind of an emotion that's always present for us if we really look at it.

Joanna: Is it a change that is out of our control, rather than something that we can control?

I'm thinking, personally, I feel like when I went through menopause, I felt a lot of grief over losing a sense of who I was as a younger woman, I guess.

Then I feel like a lot of anger, as we record this in 2025, there's a lot of political anger in different sides, and also anger around AI maybe taking people's jobs. All of these things are not choices that are made deliberately. They're things that are almost out of our control.

How much does grief and loss of control go together?

Karen: I think definitely. I mean, I think the way we cope with grief or navigate grief has a lot to do with control.

If we have any sense that I can control my surroundings, I can change what I need to change, that gives us a little bit more resilience and more ability to deal with the losses that we experience.

When it feels outside of our control and there's nothing we can do, I think that is the deeper form of grief that's very hard to manage.

As you said, because it's associated with a lot of anger. From the ego level, especially like anger, how is it that all of this can happen to me and I can't do anything about it?

Joanna: Well, let's come in to writing then. When these feelings overtake us and we really just don't know what we're doing—

Why is writing so useful when it comes to grief? How has it helped you, in particular?

Karen: Well, I think grief, as we already said, it can contain such a mixture of emotions. We typically think of grief as just being sadness over a loss, but as you pointed out, there's a lot of anger within grief, and guilt and regret, sometimes resentment. Sometimes there's even relief. There's sometimes a joy that's present within grief.

It's a very complex situation with lots of emotions bubbling up all at once, and yet, we don't know what to do with all of that emotion. So writing gives us a place to express it, to ventilate the emotion, and put it down on paper.

We sometimes hesitate to express verbally to other people all of these things that are going on with us, this mixture of emotion during grief, because other people don't necessarily understand it and may not want to listen to it.

It's why writing is our place to communicate all of these crazy thoughts we have and confusing feelings that we have. It's a safe, non-judgmental place.

We can just put it down on paper and validate ourselves that we're going through this difficult time.

It doesn't always make sense, but we can express it at least. So we can give voice to what otherwise can be hidden or repressed inside of us.

Joanna: So with your father, how did writing help you? Like was it just, “Oh, things are bad. I'm going to write this essay or this poem, and then suddenly I feel better.” Is that how it worked?

Karen: No, not at all.

Joanna: Obviously not!

Karen: I mean, I didn't even think of the idea of writing itself. I didn't even recognize that that could be therapeutic in some way.

At the time of my father's death, I happened to be reading Julia Cameron's book, The Artist's Way, where she talks about doing Morning Pages every day. I had been intrigued by that idea before of doing Morning Pages.

I found I was waking up early every morning. I couldn't sleep, dealing with this insomnia. I was actually really busy, as I was a mom and a wife and a doctor. I was so busy, I felt like I don't even have time to deal with grief or to deal with my emotions during the day. I'm just busy having to do all these things.

I would wake up at four in the morning and couldn't sleep, and I remembered Morning Pages. I started just getting up early every single morning and writing. Morning Pages, it's stream of consciousness writing, where you just write down anything that's in your head.

Much of what I wrote down dealt with, “I'm angry, I feel guilty.” I dealt with all these confusing, conflicting emotions I felt inside around my father's death.

I didn't even know for sure that was all happening inside until I started writing the Morning Pages, and it was all coming out of me.

It gave me a place to just, as I said, to ventilate and release those emotions. It actually became a place where I was processing grief without even realizing it, every morning, writing those three pages of stream of consciousness.

So that's how I began with that type of writing, and I highly recommend it. I don't know if you've ever done it. I'm sure you've read the book, The Artist's Way.

Joanna: Oh, yes. I've always kind of been a journaller, but I don't do Morning Pages like every day.

When I got divorced, my first husband left me, so it was out of my control. It was not my choice. The three journals that I have from that time are full of—and it's so repetitive. You know, there's no point in me reading it back. Maybe it's the same with you.

It's like that is just raw emotion that every single day sounds exactly the same. There is this period where that just happens.

For a period of time, you can't really get past those initial emotions in your outpouring.

Karen: No. There's so much of it inside of us that needs to come out. That's what I find, that I'm writing the same thing every day.

Julia Cameron mentions about writing these Morning Pages, it helps us eventually get out of our logic brain. Which, in grief, the logic brain, she calls it, is always trying to figure out why this happened. It's always trying to figure out an explanation. It needs an answer for all the questions.

Once you can move past the logic brain, you actually awaken the creative side of your brain, which can start to express things more in symbols and stories start coming alive.

The creative brain is actually figuring out, oh, this grief experience, this is interesting. How can I use that in a creative way to make something else?

I think, for me, when I felt that shift happen, that's when I started to move into a more productive aspect of working through my grief. That's when I was really able to start processing it better and get past all these ruminating thoughts that just came over and over again.

Joanna: I think that's what's interesting in your Stories from the Dark Night. It isn't just that stream of consciousness grief. In fact, it's not that at all. There's all kinds of different sorts of writing.

Tell us what happened when you moved into that productive side of it, and what are the types of writing that came out?

Karen: Well, I started writing whatever came to me, and I guess the Morning Pages opened that up a little bit. After doing that for months and months, one day a poem came into my head, and I just wrote it down, and it happened to be about my dad's death.

Another day, a story came to mind that I wrote about. It seemed that everything I started writing, even though I didn't think it was related to my dad's death, ended up being about my dad's death in some way or another, symbolically or in some way or another.

Gradually, I just started having these creative impulses to write some little thing. I would write down whatever came to me. I was still doing the Morning Pages every day, but at other times of day, something else would pop up for me.

I would write a story, or sometimes it was an essay. Sometimes I read a guided writing prompt that actually really helped me dive deeper into a subject. Some of the prompts were as simple as someone said, “Write something about the word ‘leftovers' and what that means to you.”

I'd think of the word leftovers, like how is that inspirational? And yet, I ended up writing a whole piece on leftovers. It was just being able to get into that creative part of my brain and writing whatever came to me.

I also then went on to more intentional writing. So I started writing letters to my dad and expressing some things that I didn't get a chance to say before he died, expressing some of the deeper emotions that I felt around his death. That was very therapeutic as well.

Joanna: On therapy, I think this is really interesting, because when my husband left—I'm very happily married people, if you're listening now, I am on my second marriage—but at that time, I didn't see a therapist. Even though we're doing a podcast, I'm not a talker. I didn't want to talk about my issues.

Writing it down, I feel like writing all of that over the years it was, really, and sort of recovering, helped me heal. So I didn't need a therapist, in some way.

Where's the balance for people between writing helping with healing and maybe needing to see a professional?

Karen: I'm much like you. I'm not much of a talker. I'm not always wanting talk with another person or looking for that kind of external help. I'm much more internally oriented. So I want to dive into my own psyche. I want to look at that. I want to explore it for myself.

I think for certain, whenever someone feels like they are just stuck and not getting anywhere and beginning to have very hurtful thoughts going through their minds, or thoughts of feeling hopeless and that they may never be able to move forward, never be able to find a way through the grief. Then they might need an outside person who can come and help them reflect.

For me, it's like my journal felt like a therapist to me. I guess I was, in some ways, dialoguing with my higher self in the journal and serving as my own therapist.

I could read back through what I wrote and see, oh, here's something I hadn't thought about before, but it's right there in what I just wrote. So this insight is there for me, but some people may not be able to do that.

They may not be able to access that higher wisdom or a different perspective through writing alone. They may really benefit from talking to someone else. So I always encourage people to seek out counseling, find a therapist, especially if talking is beneficial for them.

Joanna: I think the other thing there is—I mean, you mentioned insomnia earlier—and I do feel like there is a period of grief that is closer to mental illness, which insomnia doesn't help, obviously.

At one point, I think, in the DSM, grief was actually a mental illness, considered to be very bad, but then it was recognized as a part of the human condition.

So I guess, just to encourage people, if you're feeling like it is completely, completely mad, then sometimes that is normal. It's just a case of how long that goes on for. I guess, a bit like insomnia. You have to get that sorted out at some point.

Karen: Yes, because at some point it becomes destructive to your physical health.

If you find that you're not thriving, and that you feel, in fact, that you're falling apart in many ways, I think it's really good to get input from an outside person and get help for that.

It's funny, grief reentered the DSM this past year. They created a new category, pathological grief, that they defined so that they could include severe grief.

I think they realized, first of all, it was a mistake to say any kind of grief is a mental illness because it is actually a normal part of all of our lives.

Then when they took it out, they realized, oh, but wait, some people actually do get into a severe state of grief for which they need help. They may need medications, they may need therapy and counseling. So they made up a new diagnosis and put that back in.

Joanna: I'm glad you brought that up then, because I thought it had gone, and now it's back. So, of course there is a difference.

I think also some religious traditions, there are periods of time and ways of addressing mourning and death. Where it's like for a certain amount of time you are expected to grieve, and then at a certain point of time you are expected to—not forget it all—but to move on with your life.

It's almost like those rituals of death and dying can help. In fact, you're a spiritual person, and you do put a Matthew chapter five, “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted,” into your book.

How does a spiritual perspective help you in your life, in your writing, and for people who are grieving?

Karen: It has been important to me, and it's one of the things I gained through my work, or deepened through my work in hospice.

Observing people and families who were dealing with death in general, and how they all grappled with these universal concepts that I would say are not limited to any one religion, but actually present in all religions. Love and forgiveness and finding meaning and purpose in things.

So I gravitated toward these spiritual concepts that, again, I'm not attached to any one religion, but I like the spiritual teachings and the concepts that are universal and apply to all of them.

So those ended up being the things where I found the most comfort is being able to focus on love and just bringing more love into my life. Acting with love, through love, and finding ways to love myself even though I was feeling broken and in pain.

Then forgiveness became especially powerful as well because I realized one thing that held me back in grieving my dad was not being able to recognize how angry I was at him and that I needed to forgive him for the choice he made to end his life.

I was in denial of that for many years, and when I finally saw it like, oh, I'm hanging on to this really deep seated resentment toward him for the choice he made. I have to be able to forgive him, because for whatever reason, that's what he chose, and that's what his life came to. I'm hurting myself by not forgiving him.

So that spiritual concept of forgiveness really changed everything for me. I work with that all the time now, remembering like, oh, don't hold on to grudges. Don't be resentful. Just get over it. Just find a way to forgive because holding on to that kind of anger can be really toxic.

Joanna: Well, that is the other side of anger, isn't it? Anger is such a huge part of death and dying, no matter which side of it you're on. It's something I think about a lot.

There's so much anger at the moment in the world, and I feel like some kind of forgiveness is so important because it is just so toxic when everything is angry all the time. I guess you would have seen that idea of a good death, where—

There is acceptance of what's happening, as opposed to anger at what's happening.

Karen: Yes, and I think the anger is normal and it has a place, so we need to accept it and embrace it. Yes, of course, we feel angry. Life didn't go the way we hoped it would, like we've lost all these things, but it doesn't serve us to stay stuck there if we can hold our anger, and then see a bigger picture beyond that.

I guess that's the other thing, the spiritual perspective, for me, has become what I call it —

The galaxy view of life. Where you step back and look at everything from a bigger perspective, like looking down on planet earth where we live.

How does this experience I'm having fit into the cosmos, into everything that's happening here? How do I accept it as this is just part of life, of this vast mystery of life?

I choose to move into curiosity sometimes, instead of anger. Like instead of doubling down and being angry about what's happening, being curious about how did this arise, and what will come of it. What will happen next? What will come from it?

Then that puts me back into creative brain again.

Once you're curious, you become creative, and you can find ways of making the best of the situation that you're in.

Joanna: So we've talked a lot, I guess, about the writing we do for the self. You can put whatever you like in your journal, and it can be as repetitive as hell, and frankly, quite boring for anyone else to read.

Then, obviously, you've published several books about death, and Stories From the Dark Night has personal writing, but it is not that repetitive original work, I guess. It's different. It's been transformed.

So if people want to publish, obviously people listening are authors, how did you know when you were ready to share some of your writing about your dad and things that were difficult?

How can people move from personal writing to writing for publication around these difficult topics?

Karen: For me, I understood that I couldn't share this writing until I had clarity around it.

I needed to be free of anger and blame. I understood a lot of the things I was writing early on were filled with those mixed emotions, but just ventilating anger and blaming other people, blaming everyone, blaming life.

I realized that is not productive. I'm ventilating it. It's helpful to me to ventilate it. It's not productive for other people to read that. I want to get to that place of this higher view, where I'm not looking at it through the lens of anger or blame, I'm looking at it really more through the lens of love.

How could talking about the pain that I experienced, is there a way that could be helpful to other people? How can I express that in a way that could foster healing and growth for someone else?

That took me years to get to a place where I felt like I'm not writing out of anger. I'm not writing because I want to use my writing to hurt someone. If that makes sense to you, that's what I needed to get past. Making sure I had healed enough and I had enough clarity that I had the right reasons for putting my work out there.

Then I chose very carefully what to share. There are lots of things I didn't share.

In that book, I was trying to share examples of what I wrote. Not that the writing itself is great, but I wanted to share examples of different ways that I wrote that ended up helping with my grief, different stories or essays or poems that I wrote that were helpful to me, just to inspire other people to do their own writing.

Joanna: There are writing prompts within the book in each chapter. So, I guess the main focus is —

When we write for ourselves, it is all about us. Then if we're going to publish something, it has to be a focus on the other person.

Karen: Yes, that's primarily what I was feeling. How will this impact others? Can it be a positive thing, if I share it, that could inspire someone else and make them want to do their own writing and do their own work?

Joanna: So also in the book, you talk about lifelines, and I thought it was a great term. So what do you mean by that, and—

How might people hold on to lifelines when they're going through grief or other life changes?

Karen: For me, when I was really deep in grief, I had this image of being caught up in a tsunami, in a sense. Just like these massive head waves, like rushing over me and feeling like I was drowning at times, but somehow I would always come to the surface.

There was always something I could hold onto, just some little thing, like someone had thrown me a rope. It was keeping me afloat, and it was helping me find my way back to the shore.

Instead of getting lost and thinking about, “oh, I'm so overwhelmed with grief,” to thinking, “oh, what was it yesterday that helped me get through?” Then I would remember, oh, I heard that amazing song on the radio, and that reminded me of something Dad and I did together.

Or I would find something. I found just a little note that my dad wrote to me when I was in college. I found it in a box somewhere, and seeing his handwriting, it was so touching to me. It actually brought me joy. That little moment was like one of those lifelines.

I started just paying attention to all kinds of things that were happening. Oh, and another thing was a bird song. My dad loved the Meadow Lark. We grew up in Wyoming, and it's the state bird of Wyoming. I would, from time to time, I would see a Meadow Lark or hear a Meadow Lark sing.

I started watching for those little things, those little, tiny things. I'd be paying attention to the bird song, and I'd hear the Meadow Lark, and that was one of my life lines. Like, oh, there's dad. There's a connection with my dad.

When I started searching for the lifelines every day and just noticing and paying attention, every day there was something. Every day there was some kind of reminder that helped me feel connected to him.

Those little things I felt like were just enough to keep me afloat, when it seemed like, “Oh no, here comes the wave again. It's going to wash me under,” but I would know there will be something. There'll be something I can hang on to that will help me get afloat again.

Joanna: It's interesting because, of course, specifics, like the sound of the Meadow Lark, are what also bring our writing alive. So it's not just bird song. You know, I heard a bird sing. It's always the specifics and paying attention. I guess, again, that gives you an external.

You're looking outside of yourself, not just being stuck in your head.

Which can, again, just help you keep going.

Karen: Yes, definitely. Looking for all the little symbols and little signs outside of myself that reminded me of dad, sometimes even in a painful way. Oftentimes it was just poignant and sweet, the little reminders I would find.

My dad sometimes smoked a pipe with this cherry-scented tobacco in it, and the smoke always smelled like cherries. One day I smelled that. Someone was smoking a pipe with that scent, and I smelled it, and it was like, wow. It was amazing being transported, in a way, back into my childhood and being next to my dad.

It's incredible when I started paying attention just how many little reminders there were. For me, they were always very positive. Some people describe that they don't like having reminders because it makes them feel sadness over again, but for me, I always felt a mixture. I always felt the sweetness as well.

Joanna: Yes, that bittersweet, I think is the word. What about your family and other people who knew your dad?

One thing that people worry about sometimes if they publish work about family members, a memoir or something, is that other people feel differently about the situation.

So what are your thoughts on that? Did other people read it?

Was that not a concern? What are your recommendations for people?

Karen: When I started writing about it, the thing I was most concerned was my mother and how she would feel about it. Initially, I told my mom I had written some stories and they have to do with my dad's death.

She said to me, “I don't want to read them. Don't tell me anything about it. I don't want any of that. Don't talk about it or tell me anything.”

Then I was really worried, like, oh no, if this is out in the world and other people comment to her, or other people read it, it will be upsetting to her. Then the very next day, she called me, and she said, “Read the story to me.” So she had to get to a place of comfort.

For me, it was a real dilemma. Do I put this out in the world if my mom can't bear it, can't bear that this information is out there? So I read her the story, and the story was just my story of my experience.

That's what I told her. I'm not writing about what I think my dad experienced. I'm writing about my experience with grief when I found out my dad died and what that was like.

So I really did keep it true and honest to my own experience, without trying too much to conjecture on what my dad felt, or what anyone else felt, or anyone else's actions at that time.

I kept to writing about what I experienced.

Anyway, I read the story to her. We cried together. She loved it. It was actually this incredibly positive healing moment for the two of us because we hadn't been able to speak so deeply about our grief together in all these many years since my dad had died. That story is what unlocked it for us.

Joanna: Oh, that's wonderful. Sometimes it can be a way to bring you together. I mean, again, we both said we're not really talkers. I sometimes feel like I wish my family could read my books, or would be interested in reading my books, so they might understand how I feel.

I wouldn't be able to say it out loud, whereas I can say it in writing.

It's funny because I used to write a lot of letters, like up until a decade ago, or maybe two decades ago now with email—gosh, time flies.

I used to write so many letters in my teens, and then when I was backpacking in the early 2000s. I feel like maybe that's something we don't do so much anymore.

Karen: Yes, that's so true. Like you, I think talking is difficult sometimes. To talk together about a painful subject, it's sometimes really hard to find the words. We're in our left brain all the time try, and we're censoring ourselves constantly when we're trying to talk.

It's hard to have a really deep conversation with another person, but you can just write with honesty and integrity, and be real and raw on the page, and put it down.

Again, for me, it's like I described before, I waited a long time before writing the story and then sharing that story. It was until I knew I did not write this to try to hurt someone, to try to blame my mom or hurt her, or my brother, or cause them any pain.

I made sure what I was writing felt pure to me. So I think that's why it had a positive impact for her.

Joanna: Well, we say we would rather write, but we both have podcasts, and as we come towards the end, I wanted to just ask about your End of Life University Podcast, which I've been on. So tell people about that and—

What can people find on your End of Life University podcast?

Karen: I started the podcast after publishing my first book, 7 Lessons for Living from the Dying, and realizing nobody really wants to buy a book about dying. People don't talk about this. Nobody wants to hear about it.

I realized it's not enough to write a book, I have to do something else to try to change this conversation around these topics. So I got the idea then. I started listening to podcasts myself, and thought there needs to be a podcast on this subject.

So I started doing interviews, and I discovered your podcast shortly after that. I loved your style. I love the fact that you have a more eclectic podcast, that you go in lots of different directions, and you're just interested in everything. So you have lots of different guests, a variety of guests with a variety of topics.

I decided that's what I'm interested in, too. So I kind of modeled my podcast after yours. Inviting lots of different guests and having different types of conversations, thinking whatever we put out there should be helpful to someone.

The more people are able to hear conversations about difficult topics, the more comfortable they may get with having these conversations themselves. So I've been doing it for, well, I actually started in 2013 with my first interviews back then. So it's been a while, like you. Not as long as you have been, but a while.

Joanna: That's amazing. You do have so many different interesting topics and angles and different kinds of people. So has the reception been what you wanted?

I mean, you've obviously been doing it for so long, it's still of value to you and your community.

Karen: Yes. I don't really even know what I expected in the beginning. At first, I only attracted people who already worked for hospice, people who were already in the field and already had an interest.

Over the years, I've attracted more and more people who are just being themselves introduced to grief and death in their own lives.

I've received some amazing feedback and wonderful stories from people.

One young man told me a friend of his was dying, and he drove across the country to be with his friend. He listened to the podcast all the way there in the car so that he would understand death and dying and grief. He said it made all the difference.

He said, “I came to his bedside and I knew what to say, and I knew how to be with him and how to be comfortable with my own pain and grief because of all the interviews I heard.”

It was like, oh, wow, that's why I'm doing this. That's why I'm doing this, so —

It's a resource for people in a time of need who need to learn about something and want information.

So when I get feedback like that, it tells me, okay, this is why I'm doing it. It keeps me going, really, because it's actually hard doing a podcast. It's such hard work.

Joanna: Wow, you gave me goosebumps there. I know people listening will be affected by that because every single person is going to be affected by grief at some point. Whether it's ourselves or other people, it's going to happen. So I absolutely recommend your podcast and your books.

Tell people where they can find you and everything you do online.

Karen: If they go to the website, it's EOLuniversity.com. EOL stands for end of life, but EOLuniversity.com. A link to the podcast is there, and to my books, and pretty much everything they need to know about me.

Joanna: Brilliant. Well, thanks so much for your time, Karen. That was great.

Karen: Thank you, Joanna. I've really enjoyed it.

Leave a Reply